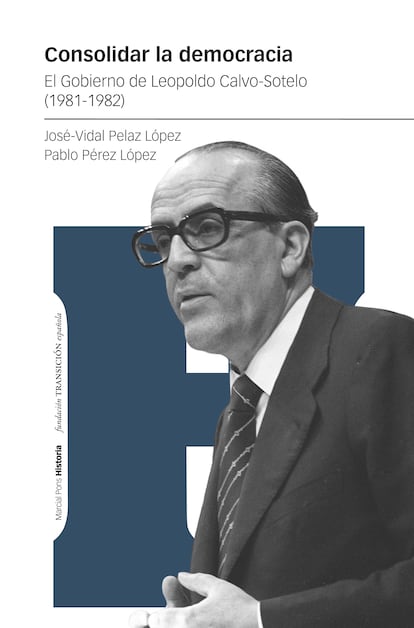

'Consolidate democracy': A vindication of the brief and difficult Calvo-Sotelo government

A type of opinion piece that describes, praises, or criticizes, in whole or in part, a cultural or entertainment work. It should always be written by an expert in the field.

Madrid native Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo (1926-2008) was the shortest-serving Prime Minister since the return of democracy to Spain. He led the government for 21 months (from February 1981 to December 1982), sandwiched between the period of the charismatic Adolfo Suárez, whom he succeeded, and the historic and long period of the Socialist Felipe González. In the midst of the upheaval in Spanish society following the attempted coup of February 23, 1981 , Calvo-Sotelo had to face an extremely complicated situation, one that required consolidating the democratic regime while keeping a close eye on the military, confronting ETA murders , and an economic crisis with 15% inflation due to oil prices. “An economic flood,” as contemporary history professors José-Vidal Pelaz López of the University of Valladolid and Pablo Pérez López of the University of Navarra describe it in their exhaustive essay, “Consolidating the Regime: The Government of Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo (1981-1982) ,” published by Marcial Pons.

In the book, the authors give value and luster to a period that should not become "the missing link of the Transition," they say. It was the moment of the smooth assembly of a state with 17 nascent autonomous regions that, as we can still see today, still fails to satisfy Catalan nationalism despite the concessions. Nevertheless, for historians, "the foundations of the State of the Autonomies" were laid. The book also recalls the rapeseed oil health crisis, which would eventually cause 400 deaths and haunted a government that failed to take responsibility.

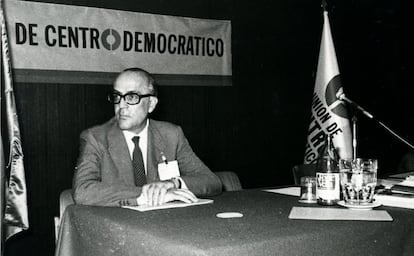

All of this with a governing party, the Democratic Center Union (UCD) , which quickly fell into disrepair due to its personal biases and internal struggles between different factions, from the Blues to the Social Democrats. "What could a president who had arrived at the Moncloa in those circumstances propose to himself and to the country?" Calvo-Sotelo asked. And in a legislature shortened after Suárez's resignation at the end of January 1981, the authors blame several people for the UCD's hara-kiri, such as Suárez himself, who neither left the party nor gave up his attempts to supervise his successor.

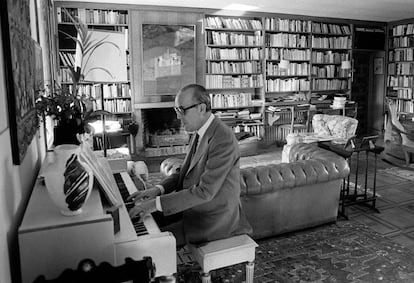

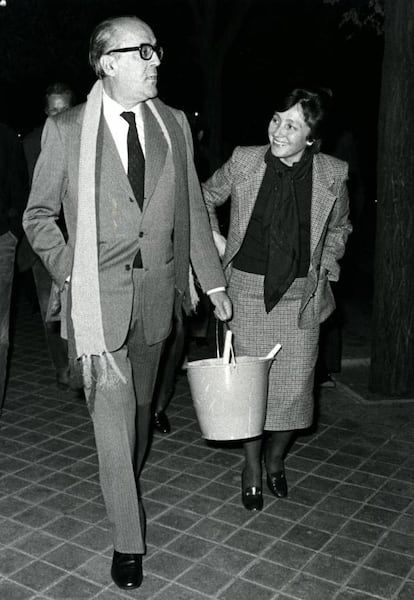

He was a technocrat, a conservative, cultured (with a library of 15,000 volumes), a polyglot (he spoke English, French, and German), a dour man who rarely smiled, and who strengthened democracy, the authors emphasize. He also put Spain back on track in the international order with its entry into NATO in June 1982, breaking decades of isolation, while awaiting negotiations for entry into the European Economic Community. He also contributed to finally subordinating military power to political power (he ordered an appeal to the Supreme Court against the sentences of those convicted in the 23-F coup, considering them lenient). And during his tenure, he secured the return of Guernica to Spain.

The book provides previously unpublished sources, such as papers from the president's archive provided by his family and drafts of his reports and speeches, which demonstrate his meticulous preparation. In addition, several of his Moncloa collaborators have been interviewed, and there are references to his memoirs and to what was being published in the press at the time, particularly in this newspaper.

Calvo-Sotelo had experience in banking-related entities and had served in various cabinets under the Juan Carlos Monarchy , eventually becoming Suárez's second vice president. In a meeting between the party's and government's leading figures, Calvo-Sotelo was voted in as Suárez's successor, but the chosen one resigned from leading the party, "a serious mistake," as he himself acknowledged, and one he attempted to rectify by taking the reins when the ship was sinking.

Agustín Rodríguez Sahagún , a Suarez supporter, was appointed to lead the UCD. Calvo-Sotelo maintained "a difficult relationship from the outset" due to the former's attempt to "supervise government action, which Moncloa considered unacceptable," historians emphasize. In this situation, internal disputes over the divorce law and TVE's unfriendly stance toward the government on several issues ultimately undermined the party. At the same time, the gap between Calvo-Sotelo and Suarez grew increasingly "unbridgeable."

The new president wanted to convey the message that with Suárez's departure, the Transition had ended and, therefore, a new era had begun with him. After a first investiture vote in which he failed to secure the necessary majority, the second, scheduled for February 23, 1981, went down in Spanish history for the shock of the Tejerada ( the Tejerada protests), which Calvo-Sotelo defined as "three dramatic minutes and 17 grotesque hours." On February 25, normality returned, and he was finally appointed president at the age of 54.

The other "anti-democratic pincer" was terrorism, especially ETA, with its significant social support in the Basque Country, the ambiguity of the Basque Nationalist Party, and the refusal of Mitterrand's France to cooperate with Spain. The book emphasizes, at least, the negotiations with the political-military branch of ETA, "the possibilists," who laid down their weapons. Despite everything, ETA murdered 63 people during those two years of its presidency.

The poor results in the regional elections in Galicia and Andalusia led Calvo-Sotelo to resign as leader of a party divided on both the right and left. He then brought forward the elections , which would bring a landslide victory for the PSOE and the collapse of the UCD, which fell from 168 seats to 12. The final pages of the book recount the long transfer of power, "characterized by collaboration." Years later, Calvo-Sotelo would reiterate that the legacy he left González was much better than the one he had received.

438 pages. 36 euros

EL PAÍS