'Paracuellos', a comic book account of the hunger and brutality of Franco's regime

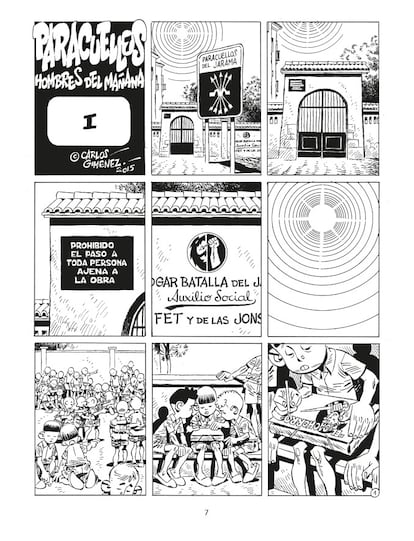

When Carlos Giménez submitted the first Paracuellos comic , his brutal autobiographical novel about a post-war boarding school, the editors of Mata Ratos magazine weren't too pleased. It was 1976, and remembering the pain, hunger, and beatings of the post-war period was very difficult back then. They accepted the second installment, especially because they needed to fill a few pages, but told him not to bring any more. After knocking on more doors without much success, he managed to get an 18-page volume published by a publisher associated with El Papus , the humor magazine that suffered a fascist attack that same year. But the print run was very small and the impact was minimal. Success came unexpectedly, after the comic captivated French readers and from there spread to Spain.

At 84, Carlos Giménez is a giant of Spanish literature—he has won every major award a cartoonist can receive. He doesn't even remember the number of comics he's published over a career spanning almost seven decades (in fact, he's been drawing comics since he was that starving child of the post-war period). He rarely leaves his home in the center of Madrid, but he continues to work tirelessly. Creators as diverse as Juan Marsé, Gonzalo Suárez , and Guillermo del Toro, who was partially inspired by his comics in The Devil's Backbone, have asserted the importance of Paracuellos in the Spanish collective memory.

As the 50th anniversary of the first comic book approaches, Reservoir Books has published all the volumes of Paracuellos in a single volume—a marvelous, nearly 600-page tome weighing three kilos and requiring a wheelbarrow—(the publisher has had to withdraw the first edition because some pages were missing, and will replace it with a new copy for those who have purchased it. The second edition comes out on July 30). Reino de Cordelia publishing house released another version of Paracuellos in 2024, in novel form, for "those who don't read comics." In this adaptation, the panels become stories, although it is profusely illustrated.

Paracuellos is an immense journey through the memories of a dark time in which there were also glimpses of humanity. “Memories remain, increasingly distant and diluted in time,” Carlos Giménez explains via email. “Sometimes I struggle to separate the memory of what I experienced from the memory of what I recounted. And what remains, however, is the satisfaction of having managed to recount, despite the many difficulties, what those Falangist schools were like in postwar Spain.”

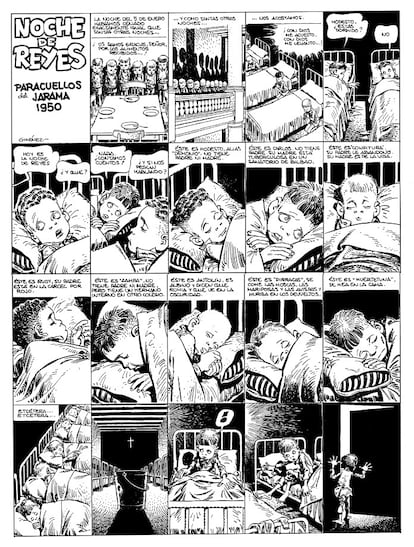

One of the most interesting things about reading all the Paracuellos in a row is noticing how, over the years, the harshness of the early comics, sometimes unbearably brutal, gives way to a more optimistic view of humanity, with people who help children, who feel sorry for them, who try to stop the violence that surrounds them. In one of the first comics, he describes the following scene: “The Falange instructor Mistrol slapped the boy Antonio Sánchez 72 times. This happened in 1948 at the General Mola home in Madrid. Antonio Sánchez was seven years old and wet himself from the beating.” In one of the last ones, he talks about Mr. Aurelio, the adoptive grandfather of Giménez's alter ego , Pablito, who, when he sees a teacher hitting a child with a shoe, confronts her and shouts: "Heartless woman! You should be ashamed of yourself! Don't you feel ashamed hitting these poor children, who have no father, who have no mother? I hope I never see you hit a child again!" This entire edition is dedicated to him, who was called Evelio in real life and with whom Giménez never lost contact.

“When I began drawing these stories, unsure how many pages I could write and publish, I chose to first tell what I considered most important and necessary to denounce: hunger, thirst, fear, religion, abuse…” explains Carlos Giménez. “Then, as I had more paper [the first stories were only two pages] and the possibility of being published, I expanded the themes and took more time to describe things with more nuance. But it's also possible that, as you say, as I told these stories, I was exorcising my bad memories.”

Regarding the problems he had publishing his first comics, he recalls: “No one in Spain wanted to publish them. I suppose it was because they were considered strange, uncommercial, gruesome... Keep in mind that these were the times of what was called the "destape" (uncovering). Franco had died, and magazine editors wanted comics with humor, the exact opposite of what I was determined to tell. But the editors of the French magazine Fluide Glacial, Gotlib and Diament, came across these pages and became interested in them. Which was quite remarkable because they ran a humor magazine. Once the French published them and they were accepted and positively reviewed by critics and the public there, all the editors wanted to publish them in Spain. And since then, they've been published in many places.”

Giménez was born in the Madrid neighborhood of Lavapiés in 1941. He lost his father at a young age, and at the age of six, his mother fell ill with tuberculosis and was unable to care for him. He was then placed in the Social Assistance homes, controlled by the Falange and the Church, which imposed a regime of terror and brutality on children. He spent eight years in the home that gives the series its title, called Batalla del Jarama, located in the Madrid town of Paracuellos. From that immersion in the violence of fascism, he has been left with a concern for the fragility of democracy, lifelong friendships, and an ability to put everyday problems into perspective. But it has also left a profound mark on him: an absolute respect for food.

He has never forgotten hunger. In fact, his next autobiographical saga, Barrio, begins when he returns to his mother's house, now recovered from her illness, and for the first time eats fried eggs, the ultimate symbol of post-war delicacy. "During the eight years I was a resident in those homes, I never ate an egg. Eggs didn't exist in those schools. It was one of the many things that didn't exist. Fortunately, this ugly time is over now. I hope it never happens again," he notes.

The widespread violence towards children is one of the things that most shocks when reading Paracuellos : beatings, threats, physical punishment, constant brutality... In the epilogue to the complete edition, Giménez explains that, in reality, those homes were a reflection of Spanish society in the 1940s and 1950s: "It was completely normal and everyday for sergeants to beat recruits in the barracks, teachers to mistreat students in schools, officers and owners to slap apprentices in workshops, and husbands to beat wives and parents to beat children at home. And I'm not going to mention, because it's well known, the treatment given to detainees in police stations, prisoners in jails, poor lunatics in mental asylums, or rebellious kids in reformatories."

For all those who try to minimize the violence of the Franco dictatorship, Giménez's comics reflect the ruthless reality of a country immersed in ignominy and revenge. The first Paracuellos comic perfectly summarizes what the comic book artist intends to convey: his stories are real and, at the same time, become a metaphor for what happens throughout an entire country. Two starving children escape to rummage through the garbage and eat anything, including orange peels. They are caught by a child who acts as an informer for the Falange instructor, Antonio (surely the most sinister character in the entire saga). He leaves them without a snack—he gives it to the informer—and forces them to beat each other up (with the threat that if they don't, he'll beat them up himself, and it will be much worse). That was Spain in the 1950s.

Asked what his comics can tell the new generations who are increasingly alienated from Francoism—this November marks the 50th anniversary of the dictator's death—Giménez responds: “I don't know. Perhaps I'd like to know what a small part of our country's recent history was like, how we poor children lived in Franco's institutions. I want to know that that was a bad time and that we have to fight to ensure those situations don't happen again, to ensure fascism doesn't re-enter our lives. Democracy, despite its many flaws, is very beautiful, and we have to fight for it.”

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fc76%2F696%2F723%2Fc76696723af3498010519efd24884ae4.jpg&w=3840&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fc54%2Fae0%2Ffd7%2Fc54ae0fd74aba825f788c7433a71b5ae.jpg&w=3840&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F8cd%2Fa96%2F365%2F8cda963658eee2b225027abb1082e3e5.jpg&w=3840&q=100)