Despite the scorn, Jane Austen is still alive 250 years later

By now, in 2025, it's hard not to have noticed that we're in the year that marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen 's (United Kingdom, 1775-1817) birth. For months, new editions of her novels have been gleaming in shop windows, some published in commemorative boxes, such as those released in Spanish by Planeta , Penguin Random House , Alianza, Nórdica , and Alba, a publishing house that has always considered Austen one of its flagships.

Tributes are taking place all over the world, especially in the United Kingdom, where the author is so highly regarded that she is often compared to Shakespeare, as Harold Bloom also did in his famous Western canon. The scope of the celebrations is evident in London's bookstores. The new releases table at Hatchards, the London bookshop that made Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway dream, is full of carefully curated and colorful editions of all her works, but also of suggestive new titles, such as Jane Austen and George Eliot: The Lady and the Radical (Biteback Publishing, 2025) by Edward Whitley, or Living with Jane Austen (Cambridge University Press, 2025), a moving book by Janet Todd, who has devoted much of her life to studying her works. Faced with such a beautiful treasure, any Janete (the name by which Austen fans around the world recognize themselves) would have felt in heaven.

In addition to the reissues, the Jane Austen centenary leaves other valuable contributions in Spain, such as the publication of the essays Two Evenings with Jane Austen (Alianza, 2025) and In the Footsteps of Jane Austen (Ariel, 2025), both by Espido Freire, an English philologist and the writer who has most contributed to the dissemination of her work in our country. New surprises are planned for the autumn, such as The Novelistic Life of Jane Austen (Impedimenta, 2025), a graphic novel by Janine Barchas and Isabel Greenberg, and My Aunt Jane (Anaya, 2025), an exquisite biography aimed at young audiences also written by Espido Freire. And it is possible that as December 16th approaches, the day Jane Austen would have turned 250, other literary and audiovisual proposals will appear (such as the series Miss Austen ).

“It's obvious that Austen is being read a lot in Spain,” says Martín Schifino, editor at Penguin Random House. “There are constantly editions appearing for all audiences, both young adult and adult, romantic in style, but also for university students, in paperback, with inflected edges, illustrated…” Centenary releases help a lot, he adds, although he believes that film adaptations in recent decades have also boosted sales.

Misogyny and ignoranceHowever, if we look back, it's also clear that Jane Austen hasn't always enjoyed such a healthy publishing presence in Spanish. "She's an immense author," says José C. Vales, one of her main translators, "full of wonderful details and jokes that haven't always been understood." The first work translated into Spanish was Persuasion, in 1919, a century after her death . And, until not so long ago, mentioning her name in intellectual or university circles was tantamount to being labeled a sentimental or saccharine reader. Misogyny? Probably. Ignorance? Definitely.

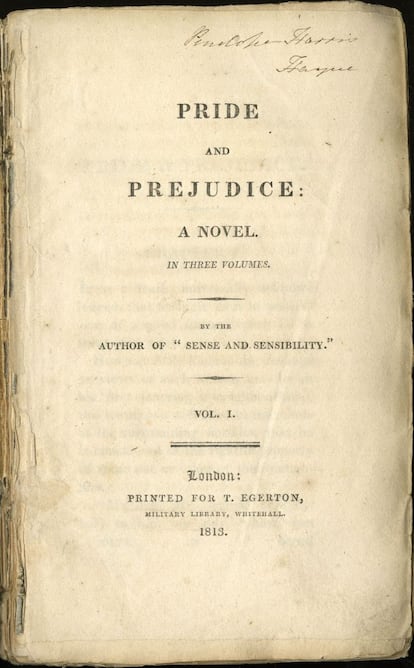

Postwar translations also helped to pigeonhole Austen as a minor author, a "romance novelist," a derogatory label if ever there was one. Proof of this is the curious edition of Sense and Sensibility published in 1958 in the literary magazine Novelas y Cuentos under a most eloquent title: Towards Happiness by the Road of Love . Or the no less curious version of Pride and Prejudice that appeared in the Colección Violeta (Violet Collection) of the Molino publishing house, with a cover illustration by Joan Pau Bocquet Bertrán, who also drew amusing comics. But among all these relics, the most notable is In Mansfield Park , published by Tartessos in 1943. In addition to its amusing title, a copy of another French translation, this version of Mansfield Park hides an anecdote that would have made Jane Austen herself laugh. Guillermo Villalonga, his translator, decided to take the liberty of omitting the ten chapters in which the characters rehearse a play, precisely the same ones that literary critics, with Nabokov at their head, consider not only the most accomplished, but also one of the great peaks of the 19th-century European novel.

Although Sergio Pitol and José María Valverde had already produced important translations of Emma in the 1970s, it was not until the 1990s that Luis Magrinyà, responsible for numerous classic editions at Alba and himself the translator of Judgment and Sentiment , published Austen with the care and seriousness that a classic such as her deserved. Among other things, it was Magrinyà who commissioned Francisco Torres Oliver, National Prize winner and pioneer of Gothic literature in Spain, to write the dazzling translation of Mansfield Park for Alba, which, needless to say, includes every chapter. “I’ve been rereading Mansfield Park and refreshing what Nabokov explains about the work,” Torres Oliver comments in a generous email exchange. “It’s an analysis that makes you love literature. I’ve also seen that Martín de Riquer compares it to a string quartet; I think that, musically, it would be better to compare it to a baroque concerto, if only because of its three-movement layout. But we all know that its essence is theatrical: it’s a drama, or a comedy of intrigue, as Nabokov wants it, whose pieces he works with millimetric precision.”

Returning to centenaries, they not only constitute an exceptional opportunity to revise translations and reissue works, but also, as Magrinyà points out, for new generations to offer different interpretations of established authors. Or, as AS Byatt would say, they serve to judge the extent to which the presence of a writer like Jane Austen lives on among us. In the case of Spain, it is true that Austen has needed two centuries for her figure to become better known. It has also taken her two centuries for her to find her true place in bookstore windows and on library shelves. But, despite the obstacles and numerous disdainful remarks, she has finally managed to enchant and possess Spanish-speaking readers. And if she has succeeded, it is because her ghost lives on.

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F26e%2F7bd%2Fd37%2F26e7bdd37269e6439b3d1760e8ca5901.jpg&w=3840&q=100)