Elena Poniatowska: A Loving Memory of Julio Cortázar

AND

In my life, meeting and interacting with Julio Cortázar was a huge event. And I can't help but celebrate his upcoming birthday and think that, if he were with us, we'd sit down and celebrate his 111th birthday. Unfortunately, no one lives to be 100, and no one is resurrected, but great men, writers of his stature, leave an indelible mark.

Julio Cortázar was born on August 26, 1914, in Brussels. I visited him for the first time in Paris in 1955, accompanied by a business card from Carlos Fuentes. Seeing him in his apartment with his wife, Carol, was a gift from life. Julio happily lived with the writer Carol Dunlop, with whom I became good friends, although unfortunately I would never see her again.

In 1954, Carlos Fuentes gave me a card of his (one of those small ones called "visiting cards") to knock on the door of Julio Cortázar's apartment building in Paris. Julio had just published Bestiario . The card was so affectionate that, instead of giving it to the great writer (more French than Argentine), I treasured it because it said: "Treat her with affection, she's my person." I didn't ask any questions because he treated me affectionately, like a friend, and we forgot about the interview. I would do it years later in Mexico with my great friend and coworker, my unforgettable friend and that of Carlos Monsiváis, Margarita García Flores, who did notable radio interviews on Radio UNAM and, above all, interviews far superior to mine, since in addition to her program on Radio Universidad and her publications in the Revista de la Universidad and the Gaceta –which she also directed– she was one of the top brass, she prepared her questions thoroughly and her knowledge of the subject was evident, so evident that she became the Press Director of the Revista de la Universidad and published a compilation of her excellent interviews.

In addition to visiting Julio Cortázar in Paris, I met him again at the Hotel del Prado in Mexico City when he headed the Russell Tribunal that judged the crimes committed by Pinochet in Chile. The tribunal held sessions in the Salón de los Candiles, which almost disappeared, along with the hotel and, above all, the Diego Rivera mural, during the 1985 earthquake.

I interviewed Julio with Margarita García Flores, who performed infinitely better than I could, and years later I had dinner with him, Marie Jo, and Octavio Paz in Mexico. In Paris, we spoke in his apartment at 9 Place du General Beuret, where he was already married to Carol Dunlop. The spell of that afternoon in a state of grace remains among the happiest moments of my life, and it still pains me because Carol would die very young. Also, sadly, Julio would follow her shortly after.

Cortázar was an active member of Amnesty International, human rights associations, democratic fronts for the defense of the people and national liberation, as well as other causes linked to the discontent and suffering of the peoples of Latin America, such as El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Cuba. By then, Latin American literary critics had declared that Hopscotch is to Latin America what James Joyce's Ulysses is to Ireland and Scotland, and the endearing figure of a tall, committed Cortázar had become a central figure in the culture and humanism of our continent.

At that time, Antonioni had already filmed Blow Up , based on the story “The Devil’s Beard” by Cortázar.

At 93, I think of Carlos Fuentes and his vitality; of Gabriel García Márquez and his yellow butterflies; and I remember with special devotion Julio Cortázar, who would have turned 111 on August 26th of this year. They're all gone now: Octavio Paz, Carlos Fuentes, Julio Cortázar; I even often remember the laugh of Mario Vargas Llosa, who was the youngest.

Julio Cortázar's passion for dictionaries makes me think of the immense affection I have for an old thesaurus that has been my salvation since my daughter Paula left it in her bedroom when she moved to Mérida, Yucatán.

“Strange things always happen to me,” Julio Cortázar explained to me at the Siglo XXI publishing house in Mexico. “I remember an effusive lady who came up to me to congratulate me: “I love your stories, and so does my son! Don’t you want to write a story in which the main character is called Oily Harry?” I suppose my reader wanted to please her son. And I’ll confess something to you, Elena: I was tempted to write a story about Oily Harry.”

–And what other temptations do you fall into?

–In many.

On that occasion, he laughed, and his teeth, the two front ones separated, looked like a child's. If they weren't stained with nicotine, I'd say they were milk teeth. If I think about it, Julio was all milk, he was nourishing, he was good, he warmed the soul, and he let himself be drunk by anyone who approached him. He never kept his distance; there was nothing showgirl-like about him. He never mocked his interlocutors; he accepted our ignorance, our weakness. It was impossible to feel bad about him. No wonder women flooded him with letters.

–What temptations did you fall into as a child? Those kinds of questions are of great interest to all your girlfriends, of whom there are many in Mexico!

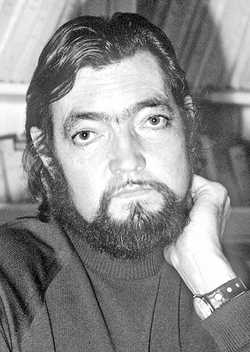

▲ Argentine writer Julio Cortázar – who would have turned 111 on Tuesday – in Paris when he received the Médicis Prize for his work The Book of Manuel , in 1974. Photo AFP

–Memories from childhood and adolescence are deceptive. Temptations? I felt bad as a child.

-Because?

–I was sickly and shy, with a vocation for the magical and the exceptional that made me the natural victim of my more realistic schoolmates. I spent my childhood in a haze of goblins, elves, with a sense of space and time different from that of others. I recount this in Around the Day in Eighty Worlds , and enthusiastically lent it to my best friend, who threw it in my face: “No, this is too fantastic,” he said.

–And you never had the desire to be a scientist, to discover the why of things?

"No. I always wanted to be a sailor. I read Jules Verne like crazy, and all I wanted was to repeat the adventures of his characters: embarking on a ship, reaching the North Pole, crashing into glaciers. But, you see"—he drops his hands—"I wasn't a sailor, I was a teacher."

–So, your childhood was cruel?

–No, not cruel. I was a very well-liked child, and even those same classmates, who didn't accept my worldview, admired someone who could read books they couldn't grasp. The thing is, I was devastated; I didn't feel comfortable in my own skin. Before I was 12, puberty hit, and I began to grow a lot.

–Didn’t being so tall give you confidence?

–No, because they make fun of tall people.

–I thought being tall gives you a lot of confidence.

"Well, you're wrong," he cheers up. "There's a story that resonates deeply with me: 'The Poisons.' I had terrible childhood loves, very passionate, filled with crying and a desire to die; I experienced a sense of death very, very early on, when my favorite cat died. This story, 'The Poisons,' revolves around the girl from the garden next door, with whom I fell in love, and an ant-killing machine we had when I was a child. It's also the story of betrayal, because one of my first anguishes was the discovery of betrayal. I had faith in those around me, and that's why the discovery of life's negative aspects was terrible. This happened to me when I was 9 years old."

–Julio, you always describe children and adolescents as endearing and, above all, suffering.

–As a child, I wasn't happy, and this left a deep mark on me. That's where my interest in children, in their world, comes from. It's a fixation. I'm a man who loves children very much. I haven't had children, but I deeply love little ones. I think I'm very childish in the sense that I don't accept reality. I tell children fantastical things and immediately establish a good relationship with them, a very good one. What I don't like at all are babies; I don't get close to them until they become human beings.

–I think the children in your stories are moving because they are authentic.

–Yes, because there are very artificial children in literature. A story I love very much is “Miss Cora.” I experienced the situation of that sick adolescent, and, as I told you, I had a great experience with hopeless love at 16, when I considered 18- and 20-year-old girls to be very adult women. At the time, they seemed like an inaccessible ideal to me, and that created a situation of impossible fulfillment.

"Miss Cora" is a story I struggled with a lot. You know, one of children's fantasies is imagining themselves about to die. Then, their loved one appears, repentant, embraces and loves, cries over their guilt, swears to love them forever—in short, an archetypal situation.

–Don't you think there's a lot of self-pity in all this?

–I rather believe there's a definitive aptitude for returning to a child's worldview; I take great pleasure in writing that return; I feel good when I return to my childhood.

–From your fixation on childhood, did object-books, collages , clippings, etc., emerge?

“Yes, I like toys a lot, but the clever ones, the ones that move and act; I like them as much as I was fascinated by stationery stores, notebooks, pencil tips, crumb erasers, India ink. I smelled the Larousse Illustrated , it had a perfumed scent that still reaches me. Elena, I have an infinite love for dictionaries. I spent long periods of convalescence with a dictionary on my knees looking for the definition of “schooner,” “porrón,” “typhus.” My mother would peek into the bedroom to ask me: “What do you find in a dictionary?” For me, dictionaries were everything, and I still love them. I buy them or look for them in secondhand bookstores along the banks of the Seine in Paris.”

On Tuesday, Julio Cortázar would have turned 111, and there are many of us who miss not only Hopscotch , his Libro de Manuel , and his visits to Siglo XXI Editores when it was directed by Arnaldo Orfila Reynal, an Argentinian like him. In addition to his great work, Cortázar has remained in my heart, and I miss not only his books, but also his social commitment and the grandeur of his life on two great continents that he knew how to embrace with his writing: America and Europe.

jornada