From Beirut to California, Artemisia Gentileschi's unique journey: this is how a painting by the Italian artist ended up at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

In this story, it's difficult to start at the beginning. Because the beginning could perhaps be the end of the 16th century, with the arrival into the world of the artist Artemisia Gentileschi , daughter of the painter Francesco Gentileschi, friend of kings and noblemen, one of the few women recognized in the world of painting. But the beginning could also be the end: the exhibition since June 10 of one of her major works, Hercules and Omphale , at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California, very far from her native Italy, but even further from the place to which this piece now belongs, Beirut.

Because that's probably where this story originates. In Beirut, that Mediterranean city so often battered and devastated, most recently in 2020. Five years ago, on the afternoon of Tuesday, August 4, a massive explosion, caused by nearly 3,000 tons of ammonium nitrate, leveled everything in its path. Like the Sursock Palace, a private residence with a century and a half of history behind whose walls were housed important works of art. Among them was Hercules and Omphale, in a poor state of preservation after decades in the residence, where it was not on public display. The explosion left it more than damaged: tears, missing pieces of canvas, dirt, and dust. So much so that its owners took a step forward: they needed help. And that's where remote California unexpectedly comes in.

An article in an art journal, Apollo , tipped off Ulrich Birkmaier, a German conservationist at the Getty, and Davide Gasparotto, an Italian art curator at the center. The former traveled to Beirut to see the painting. He was impressed by the significant damage. The institution, with nearly 30 years of history, then reached an agreement with the family: they would take it to California for the time necessary to restore it, put it on display, and then return it to the family in the best possible condition. They have now fulfilled the first two parts of the agreement: the work has been almost miraculously restored. It can be seen at the Getty until mid-September; after that, it will travel 3,700 kilometers to Ohio to be exhibited at the Columbus Museum of Art . This institution has loaned another artemisia for the Los Angeles exhibition and, in return, the two will be able to be displayed . Finally, as Birkmaier promised its rightful owners, the piece will return to Beirut in 2027. And there, at last, it will be on public display.

Very few people had seen the painting before its restoration. In fact, it wasn't until 1992 that it was attributed to Artemisia Gentileschi. The Sursocks have a museum in their name, but this work was in their private palace. So Gasparotto decided to write to the owners. “And they were incredibly excited,” Birkmaier and Gasparotto recount. “They were already preparing the painting to be sent for restoration in Italy, but when we told them we were willing to restore it for free…” Wait: for free? “Yes, yes,” says Birkmaier. “We have a wonderful group, the painting council, art enthusiasts who support conservation treatment and who contribute money to projects like this,” he says.

The palace's nonagenarian owner, Lady Cochrane, survived the 2020 explosion but died a few weeks later. She had always known the work was a Gentileschi painting . When Birkmaier saw it, he had no doubts either. “You could see from the quality of the paint, the style, the marks... that it was an Artemisia,” he says, still in awe of the work. “We had only seen it in photos, and it was when I saw my colleague Davide [Gasparotto] that I suggested contacting the family to see if they needed assistance with treatment and conservation.” Gasparotto also had no doubts. “There are clear motifs: the way she places the sleeves, the collar, the lace...,” he notes. “I think if you compare it with other paintings in Naples from the mid-1630s, there's no doubt it's her,” he says; in fact, he's clear that it's purely by Gentileschi, and not a collaboration from her studio. He also reviewed documents from 1699 in a Neapolitan collection that mention a work on the same subject: "I would say with great confidence that they were referring to this one."

That was once the worst of the pandemic was over. After examining it in Beirut, Birkmaier recalls that it was "in very poor condition." In 2022, the painting was flown to the Getty. They acknowledge that it was easy to arrange the permits and bring it, carefully and by plane, from Beirut to Frankfurt, from Frankfurt to Los Angeles, on a 747, in a couple of days. There, they began to remove a top layer of paint, supposedly protective, and found extensive damage, although they also confirmed, in case there was any doubt, that it was indeed Gentileschi's work.

The damage was immense, with terrible tears, especially on Hercules' knees, in a middle section of the painting, and on Omphale's arms and skirt. This is demonstrated by a large-scale reproduction of the original, in the same room where the restored one gleams like new. The process can also be seen in a video in the gallery.

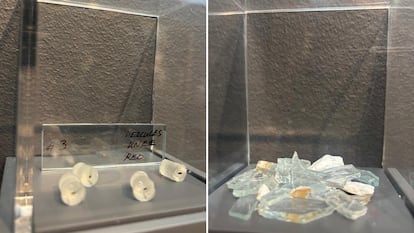

“It was difficult because of the size of the work and the extent of the damage. It was even worse because there were other restorations on top of it,” explains the conservator, who also points out the glass panes that were nailed to the painting, now on display in a glass case. In addition to being heavily darkened by the dirt of the centuries, it was reinforced with a second canvas, glued together, and also at least a couple of old restorations that had damaged it. In fact, in some areas, a virtual reconstruction was necessary: “There was a lot of paint loss, but not from the explosion. Along the bottom edge, for example; the entire foot is repainted. The toes were basically gone.”

Maximum care has been taken. The canvas has been X-rayed, and what they call "cross-sections" have been performed—tiny parts of the painting, just a few millimetric specks, have been removed so that the material it's made can be observed under a microscope.

For the past three years, Birkmaier has spent most of his time with him, workdays and non-workdays. This was the case until the last day before the exhibition, and he doesn't promise it will be the last time. The German jokes that his wife and children were even a little jealous of the work: "It's one of the conservations I've felt most privileged to do," he smiles. "You build a special relationship with the artist when you work on her paintings, and I love Artemisia's work," he acknowledges.

Gentileschi, as Gasparotto explains, rubbed shoulders with the elite of the Neapolitan, Spanish, and British courts, with the Medici, and with the Holy See. He believes she must have known Velázquez and that she painted a painting for Philip IV that was burned in the Alcázar. She didn't have an easy life: she was raped in her youth; she was married but had her daughter alone; she suffered financial difficulties. "She was exceptional. She was alone, on her own, completely," the Italian reflects.

Now, major cultural institutions such as the Museum of Rome , the National Gallery in London , and the Prado Museum in Madrid are recovering it. At the Getty, in addition to this Hercules and Omphale, more of her works are hanging these days: a Lucretia , owned by the museum; Susanna and the Elders , from a private collection (restored by the National Gallery in London); Bathsheba and David , from the Columbus Museum of Art (Ohio); and a small self-portrait of the artist, also from a private collection.

The exhibition will move to Ohio next spring, and from there the painting will return to its home: Beirut. “It’s a beautiful, incredible city. I’ve been there twice since 2022, and I think its people should enjoy it; they have a right to do so,” Birkmaier argues. “They should be able to rise again, attract tourism again.” In the end, as they acknowledge, everyone wins: both the privileged hands that have been able to complete a complex and lengthy project, and Beirut, for exposing it to the public for the first time; as well as the viewers who will be able to enjoy it in various parts of the world.

EL PAÍS