Sagarra and the Gracq legacy. And a hip flask

Strictly opinion pieces that reflect the author's own style. These opinion pieces must be based on verified data and be respectful of individuals, even if their actions are criticized. All opinion columns by individuals outside the EL PAÍS editorial team will include, after the last line, a byline—no matter how well-known—indicating the author's position, title, political affiliation (if applicable), or main occupation, or any that is or was related to the topic addressed.

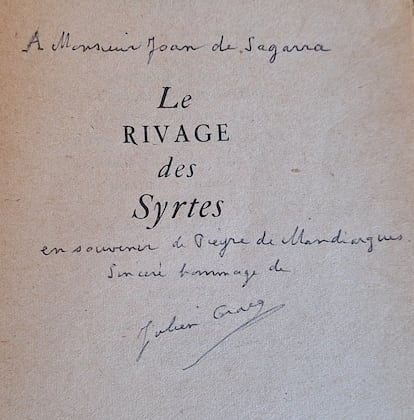

Just as one inherits an Olympic flame, over the last year, in two very obviously deliberate gestures, I inherited from my friend Joan de Sagarra two objects that have become sacred to me. One is his legendary Jameson whiskey flask on which he engraved his name. And the other, a relic, a first edition of the masterpiece Le rivage de Syrtes, dedicated by its author, Julien Gracq : “To Monsieur Joan de Sagarra…”

A hip flask. And a novel with Gracq's autograph, whom my friend Joan considered "the last classic of French literature" and whom he began talking to me about at the beginning of this century after reading my book about those who had stopped writing and noticing in it the absence of Gracq, who was then a paradigm of the writer known to be in great form, but who has become entangled in a long period of silence, an absurd withdrawal from writing. Gracq: a last bastion of what was once the great literature of France, and someone who, already in his early writings, proposed as the only valid morality for a writer an individualism somewhere between aristocratic and libertarian, and in which Joan himself may have seen himself reflected at some point.

A retired writer, so inaccessible that interviewing him at his home in Saint-Florent-Le-Vieil was considered an unattainable feat. So much so that in 2002 he published Entretiens (Interviews), a book that, as its title indicated, was a compilation of the few interviews he had ever given.

It must have been because Joan refused to resign himself to not being able to talk to Gracq, so one day, during a break in the Sunday chat, he told us that he had just spoken with a friend from Nantes, from the Octopus Club to which he belonged and which annually paid homage to Jules Verne , and that this friend had warned him that, if he sought a meeting with Gracq (who lived in Saint-Florent-le Vieil, an hour and a half by car from Nantes), he should act with cunning and under no circumstances confess to the “last classic of French literature” that he was a journalist looking to interview him.

Five weeks after that break in the discussion and when we least expected it, he used another break to tell us that he had gone to the village of Gracq and in order to communicate he had to fabricate an identity, that of a gentleman from Barcelona, of French culture, and settle in the small hotel opposite Gracq's house and from there call him to tell him that he was an old friend of André Pierre de Mandiargues who, hoping that he could dedicate it to him, had arrived in the village with a copy of Le rivage des Syrtes , first edition from 1951.

Could I come to his house so he could sign it? According to Joan, this question was followed by a tremendous silence, which Gracq himself interrupted by asking:

–Do you like rugby?

That same afternoon, while they were watching France-Italy, Gracq signed Le rivage des Syrtes for him. And I'm still amazed to have that copy on my desk today, reminding me of my promise to Joan to endure with dignity among the ruins of literature.

Do you want to add another user to your subscription?

If you continue reading on this device, it will not be possible to read it on the other device.

ArrowIf you want to share your account, upgrade to Premium, so you can add another user. Each user will log in with their own email address, allowing you to personalize your experience with EL PAÍS.

Do you have a business subscription? Click here to purchase more accounts.

If you don't know who's using your account, we recommend changing your password here.

If you decide to continue sharing your account, this message will be displayed indefinitely on your device and the device of the other person using your account, affecting your reading experience. You can view the terms and conditions of the digital subscription here.

Enrique Vila-Matas (1948). A writer who blends fiction and essay. His notable works include "A Brief History of Portable Literature," "Bartleby and Company," "Montano's Illness," "Kassel Does Not Invite Logic," and "Montevideo." He has won the Prix Médicis-Étranger, the Guadalajara International Book Fair Prize, the Formentor Prize, and the Rómulo Gallegos Prize. He has been translated into 38 languages.

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F6a2%2F705%2F215%2F6a2705215f862eb0f0574bcff7d61aa8.jpg&w=3840&q=100)