The Franco-era financial scandal that ended with a suicide in Lausanne

Historian Enrique Faes uncovers a case hidden in the archives for 60 years: an episode of capital flight in Spain, led by a Swiss bank employee and involving prominent names and companies in the post-war economy.

His body was found in the double bed of the apartment he and his wife had moved to when he had to leave his hometown because he had lost his job. Georges Laurent Rivara should not have died in Lausanne , nor should his last job have been as a lingerie salesman. He died on September 6, 1962, at the age of 46. It is most likely that he committed suicide. He had lived most of his life in Geneva and had dedicated himself very early on to the banking business. His nightmare had begun four years earlier in Spain. He, in the shadows, had been the perpetrator of hundreds of monetary crimes . The Rivara case , which broke out in late 1958, was one of the major financial scandals of the Franco dictatorship.

This Thursday it arrives in bookstores The Swiss Agent. Capital Flight in Franco's Spain (Galaxia Gutenberg) . Although the plot might seem like a detective novel, its author, Enrique Faes, is a professor of Social History and Political Thought at the UNED (National University of Edmonton), and everything described in his new book is perfectly documented. The historian's research, which connects with his biography of the Minister of Industry and Commerce, Demetrio Carceller, begins with the 20 boxes of the Rivara case file. "I initially looked for it in the Bank of Spain archives because the documents from the Spanish Institute of Foreign Currency must have been there, but I finally located it in the Economic Crimes Court Collection, in the General Administration Archive," he explains. He has also accessed documents from the Swiss Ministry of the Interior held by the Archives Fédérales (Federal Archives). He has consulted 10 more files. Just when he thought he had finalized his conclusions, he even managed to interview the protagonist's son.

In the midst of the Spanish Civil War , Rivara began working at the Banque de Bilbao en Suisse—designed in 1933 to accept deposits from Swiss depositors of the Banco de Bilbao. This entity eventually became part of the Société de Banque Suisse. It was 1951, and Rivara remained in that same position. Two years later, he made his first trip to Spain, which he would repeat in the following years with a double, opaque objective: first, to attract Spanish clients to open accounts without declaring them to the State, and then to visit them in person periodically to inform them of the status of their savings, securities, and investments. Since the business was illegal, the company sent them an internal note urging them to take extreme precautions. "Almost an abbreviated private secret agent's manual," notes the 48-year-old historian. There were no documents with clients' names written on them, and he avoided allowing them to be seen together in public or monitoring their telephone conversations. To be able to do his job, he equipped himself with a code system and trusted people with whom he could leave documentation to be sent or received by mail.

“It was a widespread practice,” Faes says. “Generic testimonies from other bankers confirm this.” The historian names two more agents, one of them with wealthy Basque clients. “It was an accessible and lucrative business.”

The Rivara case begins on November 30, 1958. An elegant man who spoke good Spanish left the Avenida Palace. It was his usual hotel when he stayed in Barcelona. Rivara got into his Opel Olympia Rekord and started it, but a vehicle blocked his way. An inspector from the Criminal Investigation Brigade opened the door, got in, and ordered him to go to the Vía Layetana police station. A place feared at the time for the torture that took place there. He didn't suffer any of it, but he didn't know how to keep silent either. The surveillance had been exhaustive. "I was surprised to discover a certain sophistication among the Francoist police who fought against economic crime; they were the first class of criminology students," explains Faes. At the police station, after a few questions, Rivara broke the banking secrecy he was bound by law in his country.

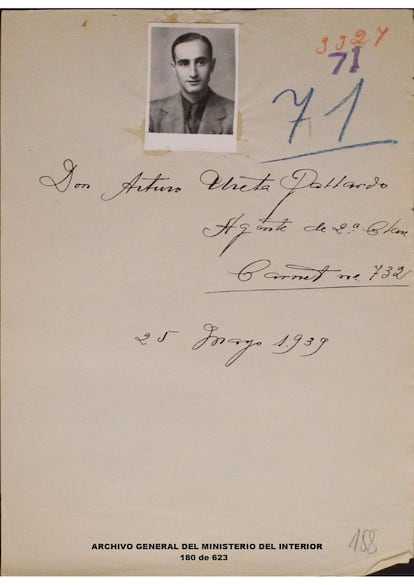

Who tipped off the Barcelona Criminal Investigation Brigade to start following him? The hypotheses ranged from a spurned lover Rivara might have had in Barcelona to the commissions the police could charge depending on the eventual revenue the case brought to the state. The investigation was led by the highly professional Superintendent Arturo Ureta. His men searched the car trunk and found the envelope containing evidence that Rivara was working with client lists from Madrid, Bilbao, and San Sebastián. Those in Barcelona also knew who to call: the prestigious notary Federico Trias de Bes . They went to his office, from there they asked him to call the police station, speak with Rivara, and it became clear that the alibi of a company they were about to set up wasn't going to fly. The notary handed over the list of Barcelona clients. Hundreds. Quite a few trusted their fate to Garrigues, a law firm with well-established international connections.

The case soon reached the desk of José Villarías Bosch, a judge for economic crimes whose work was carried out under a law passed during the Civil War and for a war-torn, self-sufficient economy. Rivara was transferred to Madrid for questioning at the General Directorate of Security (DGS). The investigation progressed rapidly in just a month, and Swiss diplomacy had little time to react. Villarías opened folders and more folders for each of the names that appeared on the lists.

On December 12, Franco brought up the matter in his monthly meeting with his ministers. He asked the Minister of the Interior to report "extensively on the police actions that led to the investigation of these facts." What Camilo Alonso Vega said is crossed out in the minutes of the meeting. It is also known that the Ministry of Commerce, headed by the developmentalist Alberto Ullastres, had explored the possibility of granting amnesty to the tax evaders in exchange for the repatriation of capital that the public coffers urgently needed. The evaders argued that they had opened these accounts abroad to gain easier access to foreign currency. The measure was never discussed. Falange , which wanted to politicize the case under its anti-capitalist pretext, reportedly vetoed it.

Political and media control of the case was rampant. The international press reported on it, using exaggerated figures. And something happened that made it completely exceptional. On March 9, after the sentences were signed, the names of the 872 people implicated in the scandal were published in the Official State Gazette . Everyone could and can find out the fine imposed on the fraudsters (it was less than expected) and how much foreign currency they had hidden in Geneva.

After legal consultations, Faes has been cautious in naming names: data protection laws and the right to honor have been used crookedly to restrict the study of the past. But the Official State Gazette (BOE) is posted online. And the list of tax evaders draws a possible map of what the geography of Spanish wealth was like in the late 1950s. They range from executives of the Grífols and Dragados companies, from Aguilar's publisher to Jordi Pujol's father, who enriched himself through currency smuggling; high-ranking officials of the regime; executives of the Swiss company Nestlé in Spain; businessmen from the already declining Catalan textile industry; and even Marujita Díaz . The Société de Banque Suisse 's motto of "trust, security, discretion" had been shattered. So had Rivara's future when he returned to Switzerland at the end of 1959. Although the company paid the fine of more than one million pesetas, he lost his job and his reputation.

EL PAÍS