War photographers by chance in Spain in 1936

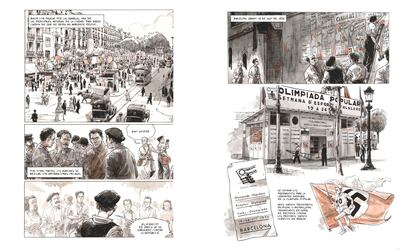

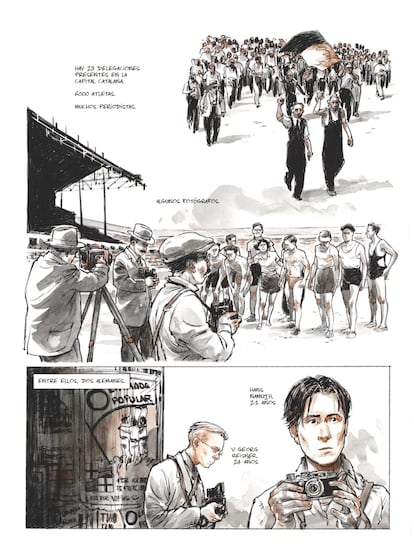

Two young German photographers, Hans Namuth , 21, and Georg Reisner , 24, arrived in Barcelona in July 1936 to take pictures of the People's Olympiad , an event that was to open on the 19th of that month with 6,000 athletes, and which was intended to be an alternative to the Berlin Games, scheduled for August—historical, above all, for the four gold medals won by a black American athlete, Jesse Owens, with Hitler as a spectator in the box. However, Namuth and Reisner, two anti-fascists who had fled from Nazi Germany, were unaware that two wars would intersect in their lives. Their story is told, in a moving tone, in the graphic novel War Photographers (Planeta Cómic) , the work of the duo formed by the scriptwriter Raynal Pellicer and the cartoonist Titwane .

Pellicer, a French father and Valencian grandparents, explains over the phone that he and Titwane have been producing "illustrated reports, some of them over 200 pages long," but that they had been thinking about creating a comic. The idea for it came to Pellicer when he saw "a photograph in Le Monde of the siege of the Alcázar of Toledo during the Civil War, signed by Namuth and Reisner." Who would they be? It caught his attention because it's unusual for war photos to have two authors and because images of the Spanish conflict are associated, above all, with names like Robert Capa and Agustí Centelles. "It was an archaeologist's job to learn about their lives."

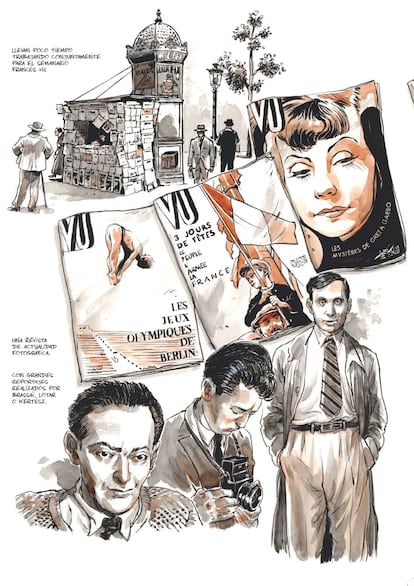

The result of Pellicer and Titwane's work was captured in a comic published in France in 2023, now translated into Spanish (a German edition is planned), with extraordinary quality drawings and a plot based on real events. "We had several sources," explains Pellicer. "First, Namuth had kept a diary, which is at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York; then I sought out relatives, like Namuth's daughter and a granddaughter of Reisner's brother, who told me things. There were also the photographs they published at the time in Vu, a left-wing French weekly with groundbreaking design."

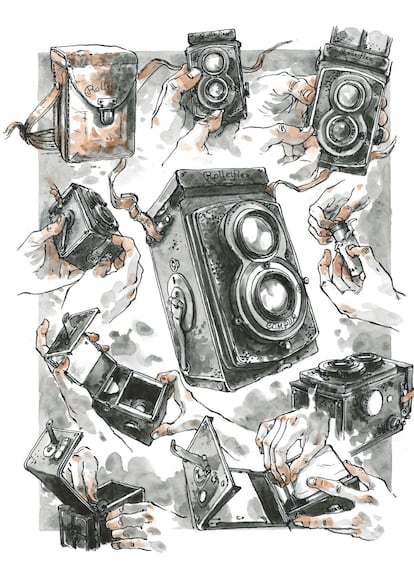

The scriptwriter had discovered that the two friends constantly exchanged cameras, a Leica and a Rolleiflex, to the point that days after taking pictures, they couldn't tell which of them had taken them. Pellicer wrote a first draft of the script, and it was time to discuss it with the artist. "Usually, I don't give him technical instructions; he works on the editing of the comic."

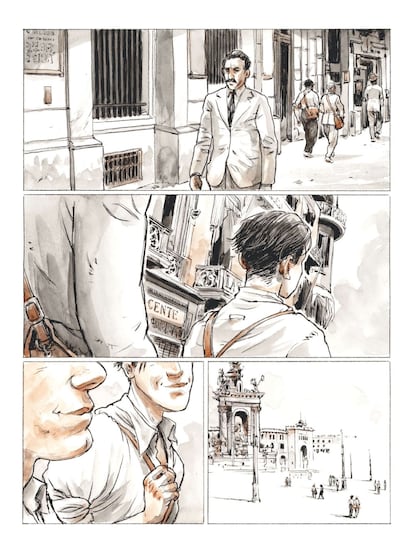

In War Photographers, it's striking that the pages chronicling the hardships suffered by the German duo, who took to the streets of Barcelona to photograph the fighting between insurgents and militias, are dominated by a pastel brown. "This story begins in July, when it's very hot, and we wanted to use a warm tone." Later, when the situation becomes more complicated for both of them, the authors switch to black and gray. "Comics have their own language, and the colors indicate what's happening."

Namuth and Reisner had arrived in Barcelona from Puerto de Pollensa (Mallorca), where they had opened their studio in the summer of 1935. Both had had bitter experiences with fascism. Namuth had been arrested in July 1933 for distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets. He was imprisoned in Essen and released because his father was a Nazi Party member, but he chose to leave his country. Reisner bore the triple stigma of being a socialist, a Jew, and a homosexual. So in 1933, he left Breslau (now a Polish city).

“So, they met in Paris. Georg's brother worked there for an association of German refugees who had fled the Nazis. Georg, who was already a photographer, suggested to Hans, who wasn't, that they work together. They settled in Mallorca to sell photos to tourists. Besides, there were a lot of Germans there,” Pellicer explains.

When they traveled to Barcelona to photograph the Popular Olympiad, which was to be a week of sport and folklore, they encountered the military uprising of July 18 hours before the opening. “For nine months, they became war photographers by chance.” Pellicer laments that much of their work was lost, destroyed by the Gestapo when Germany invaded France. “Only about 40 images remained at the ICP , saved by Namuth, and a few years ago the Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya found another 100.”

After publishing their work on the fighting in Barcelona, the two toured the front lines: Madrid, Talavera de la Reina, Toledo, and Cerro Muriano in Córdoba, where Capa took the famous photo of the dead militiaman. Artillery fire, planes strafing people fleeing their homes in horror with only the clothes on their backs, field hospitals... The horror of war remains etched in their retinas and on their cameras. As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry said of the Spanish conflict: "Here, people shoot like trees."

Upon their return to the capital, they find that, due to their sympathies for the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), which opposed Stalin, the Soviet representatives in Madrid urge them to stop taking photos and flee.

Upon returning to France, they find themselves caught up in another war, the World War. Their German status makes them suspects, so they are sent to French government concentration camps, in precarious and overcrowded conditions. When France falls to Hitler, they find themselves in a desperate situation from which they emerge with varying fortunes. Namuth enlists in the Foreign Legion. Meanwhile, his friend sees no light at the end of the tunnel: "The Nazis and Mussolini, on one side; Franco, on the other; and Pétain [the head of the collaborationist French force] in the middle," he says.

After those terrible years, Namuth, now in the United States, refused to return to war photography. He specialized in portraits of artists—Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and, most famously, his Jackson Pollock portrait—and architects, such as Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright. He was a film director of photography and traveled several times to Guatemala—where his wife was from—to photograph indigenous people. After all the atrocities he saw, he died in a car accident in 1990, at the age of 75. Reisner, exhausted from so much aimless running, had decided, in December 1940, to abandon the cruel world in which he lived.

EL PAÍS