When Julio Cortázar dared to be Julio Cortázar

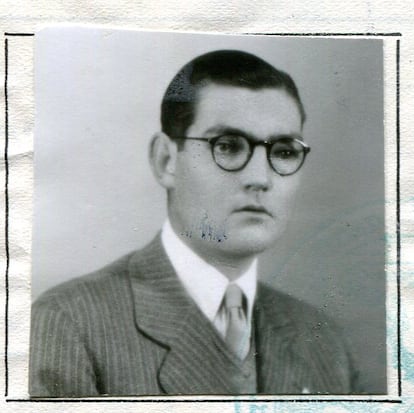

It would still be some time before he put Oliveira on the trail of La Maga in Hopscotch , his most famous novel. In the southern winter of 1944, Julio Cortázar was a lanky, hairless, and combed-back young man in his late twenties. He had just accepted the assignment to teach three literature courses at the newly created National University of Cuyo (UNCuyo), in Mendoza, Argentina, at the foot of the Andes. Until then, he had signed a collection of poems, Presencia , under the pseudonym Julio Denis, which he also used in his books and letters. A year and a half later, he left his position, definitively abandoned teaching, and buried Julio Denis under his real name. At the beginning of 1946, he justified himself in a letter to his Mendoza student, Dolly Lucero: "I want to be a writer, not a teacher!"

Mendoza writer and journalist Jaime Correas documented the author of "Todos los fuegos el fuego " (All Fires: The Fire) in his book Cortázar in Mendoza. A Crucial Encounter. (Alfaguara, 2014). From a café in the Godoy Cruz apartment, near one of the residences Cortázar occupied, Correas explains to EL PAÍS the importance of this stage in Cortázar's literary career. "When he arrives, he'd already published a few stories under a pseudonym and was working on a book," which he later destroyed. At that time, the author who would later become one of the leading figures of the Latin American boom of the 1960s had taught classes in two cities in the province of Buenos Aires, Bolívar and Chivilcoy. "The university environment" and the friendship he struck up "with the artist Sergio Sergi and his wife, Gladys Adams," opened up "a cultural universe" he had never encountered before. "This is where he finally decided to become a writer and travel to Europe," Correas says. It's even noticeable in "the tone of his correspondence. Before Mendoza, he was very formal, but afterward, he became a cronopio."

Cortázar received the offer to move to Mendoza “quite by chance,” Correas says. In a Buenos Aires bookstore, his friend Guido Parpagnoli, a professor at the National University of Cuyo, offered him the position of Northern Literature professor and two other professors of French Literature, despite the young professor lacking a degree. In the “beautiful city, murmuring with irrigation ditches and tall trees,” as he described it in a letter to his friend Mercedes Arias, Cortázar discovered an environment that, as he noted in the postscript, made him feel “like he was entering Harvard or Cornell.” He also found the lessons he taught satisfying. He told his friend Julio Ellena de la Sota that he had “enormous” fun immersing his students “in Rimbaud, Valéry, Nerval,” Baudelaire, and Lautréamont. "These people still have a lot of spiritual mountain; I cruelly come to take away their innocence, the one that Rimbaud defended with such atrocious blasphemies that sometimes make my students blush," he declares.

Necessary sacrificesIn an email conversation, Daniel Mesa, professor of Latin American Literature at the University of Zaragoza (UNIZAR), points out that Cortázar's "previous professional endeavors" in Bolívar and Chivilcoy "were seen as necessary sacrifices that interfered with his literary vocation and had to be overcome." "His university work in Mendoza," Mesa continues, "represented an important step toward overcoming this contradiction, as it brought the goal of teaching closer to his true literary interests." "Cortázar arrived at a pivotal moment for the university, established in 1939 and with a strong humanist influence," confirms Gustavo Zonana, professor of Literary Theory and Criticism at UNCuyo. The Mendoza campus "is nourished by prestigious figures," such as Spaniards Claudio Sánchez Albornoz and Joan Corominas. There, he also met Daniel Devoto, a musician and writer with whom he would share a literary generation.

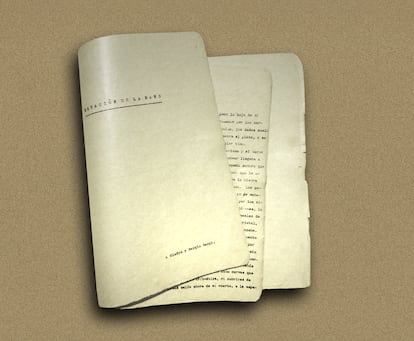

With Presencia (1938), a collection of poems “of completely classical style, with sonnets of a Mallarmean structure,” according to Zonana, “Cortázar was part of the Romantic generation of the 1940s, along with Alfonso Sola González, Eduardo Jonquières, Juan Rodolfo Wilcock, César Fernández Moreno, and Daniel Devoto, a phenomenon that was replicated throughout Latin America.” In Mendoza, “he associated with poets of his same line, such as Américo Calí and Abelardo Arias, who participated in the cultural movements of Mendoza, in which magazines such as Égloga and Pámpano stand out,” he continues. “Here he published The Greek Urn in the Poetry of John Keats in the journal of Classical Studies of the UNCuyo or his short story Estación de la mano in Égloga, along with pieces by Fernández Moreno, Carlos Alberto Álvarez, Devoto, and Calí.” He signed both texts as Julio F. [de Florencio] Cortázar. "The members of this group are not just teachers or creators, they are also cultural promoters who direct and edit magazines and translate works and authors that represent their particular literary canon," Zonana emphasizes.

But, in Correas's opinion, Cortázar's true transformation came when he wrote his short story "Casa tomada" (The House Taken Over ) , during a vacation in 1946. "That text was typed by Gladys, Sergio Sergi's wife," at the home of the writer Alberto Dánao in Lunlunta, where Cortázar had his closest friends. The story was to be included in "La otra orilla, " a book published posthumously, but it first appeared alone in the magazine Los anales de Buenos Aires, edited by Borges, and then in his first fiction book, "Bestiario " (1951). "Casa tomada is a founding short story," Mesa affirms, "it sets a tone that would be maintained throughout the 1950s, surely until "El perseguidor" (The Pursuer), which appears in "Las armas secretas" (Secret Weapons ) (1959) and is another of his most emblematic works. Both reveal "the contrast between two narrative models: the story told from a closed and rarefied environment versus the presentation of a world that an outside observer cannot access."

The expansion of Peronism and the struggle to control the UNCuyo, a dispute in which “Cortázar didn't feel comfortable on either side and declared himself independent on the side of the students,” according to Correas, drove the writer away from Mendoza, a city to which he would return in 1948 and 1973, to visit Sergi. Her influence appears in Bestiary , Around the Day in 80 Worlds, and The Image of John Keats; he even mentions her in Hopscotch . From there, he moved to Buenos Aires, where he graduated as a translator, became involved in the literary world of Buenos Aires, and met Aurora Bernárdez, his first wife, with whom he settled in Paris. In Un tal Lucas (1979), he recalled his trips to the tourist town of Potrerillos and to the border town of Uspallata, gateway to Aconcagua: “The scent of the country remains with me: the Mendoza irrigation ditches, the poplars of Uspallata…” “He loved getting lost in the mountains,” Correas says.

EL PAÍS