Memory and migration lead to Altered Territories, in the Munae

Memory and migration lead to Altered Territories, in the Munae

Exhibition comprising graphic art created over two decades by the Russian-Mexican Ioulia Akhmadeeva

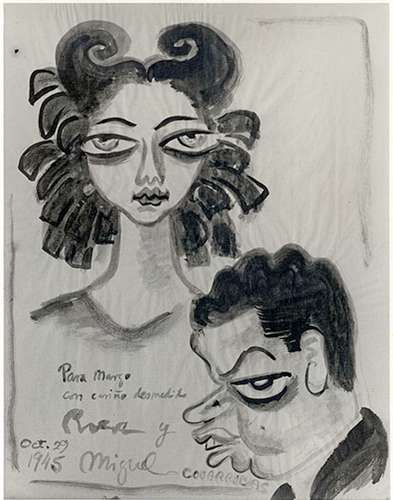

▲ This is Akhmadeeva's first solo exhibition in Mexico City. Here's one of the pieces on display. Photo courtesy of Inbal

Merry Macmasters

La Jornada Newspaper, Tuesday, May 6, 2025, p. 2

In 1993, at an exhibition of recipients of the Fonca Young Creators scholarship, the Russian-Mexican artist Ioulia Akhmadeeva (Krasnodar, 1971) saw an example of contemporary Mexican graphic art that she hadn't seen during her student days in the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). There, she had actually studied at the Taller de Gráfica Popular (Popular Graphics Workshop), which, although extraordinary

, is a work of social support

, like the official visual arts in her native country, which the young woman studied in the 1980s and 1990s.

What struck him at that exhibition was the ease with which he experimented, broke new ground, and expanded boundaries

for aesthetic purposes. This was something he noticed much more in graphic art than in painting and sculpture

, which he considered "arts that were more backward in terms of their development. I really liked this about it here. I said, 'I have to be here, learn, and do something.'"

Altered Territories is Akhmadeeva's first solo exhibition at a museum in Mexico City. It brings together a decade of work spanning 43 pieces, from graphic series—lithography, siliprint, collotype, and algraphy—and notebooks, to artist editions, object art, collage , and high-temperature ceramics, a new dimension in her production. In them, the exhibitor reflects on themes such as memory, family, migration, identity, and the transformation of inhabited spaces.

Having lived in Mexico for three decades, Akhmadeeva asserts that we are all migrants

, a statement that drives the exhibition. Throughout our lives, we move from one place to another. Aside from a few belongings, we carry our memories, in our minds, as symbolic and nostalgic keepsakes, and in objects like family photographs, archives, or letters, because these define us and tell us about our ancestors, where they lived, what they did, what their lives were like

.

Akhmadeeva was born in the south, between Georgia and Ukraine

, in a country that, as she often says, no longer exists: the USSR. Her family was predominantly female, as she doesn't remember any male presence. Listening to her maternal grandmother's stories about the war, in which both of her grandfathers fought, informed her graphic work.

At 18, she went to Moscow to study at the Russian State Academy of Fine Arts, at the V.I. Surikov Institute, specializing in graphic and easel art. There, she met her Mexican husband, whom she married in 1993. Her daughter was born in Mexico in 1994. A year after teaching drawing at the Universidad Iberoamericana, the exhibitor applied for positions at the Popular Faculty of Fine Arts of the Universidad Michoacana San Nicolás de Hidalgo in Morelia, where she has lived for 23 years.

According to Akhmadeeva, graphic art in Mexico continues to evolve, both in its urban

aspects and in the expansion of its concepts and experimentation with media. She is interested in exploring new technologies, such as laser cutting and 3D printing

, while also addressing the theme of memory—her own and that of others.

I'm currently working with Mexican migrants. This topic was in my plans before Trump declared the mass deportations of Mexican migrants. That is, connecting the memory of my experiences with those of others to interpret and make them visible by bringing them to the public and museum spaces.

The exhibition includes a very particular piece, a sort of object-art assemblage, which is also reproduced graphically. Contained Memory II includes a small dress made from a velvet fabric that her paternal grandfather brought from Czechoslovakia in 1945, and that her Ukrainian grandmother gave to the artist on her wedding day. In 1999, her mother transformed it into a dress for Akhmadeeva's eldest daughter. It is complemented by a crocheted collar with lithographic family portraits, made by her grandmother especially for Ioulia as a child, and ceramic and paper origami doves of peace.

According to the artist, graphics are what respond most quickly to the processes we experience socially, past and present grief

.

Altered Territories. Ioulia Akhmadeeva will remain at the National Print Museum (Hidalgo 39, Plaza de la Santa Veracruz, Centro) until July 6.

The UDLAP safeguards the Covarrubias archive, a unique gem.

It consists of about 30 thousand original documents from the cartoonist and his wife, the dancer Rosa Rolanda // A part can be visited online

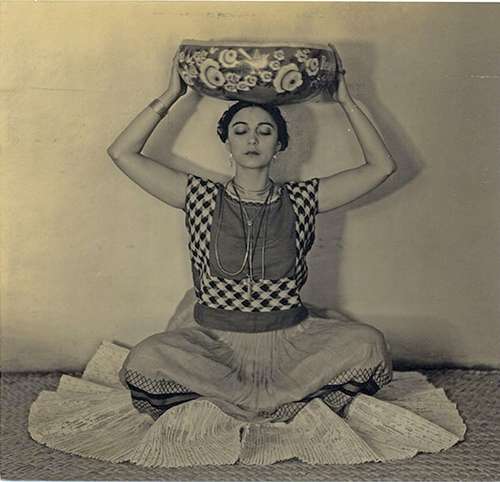

▲ Caricature of the couple, dedicated to Margo, with immeasurable affection

, dated 1945. Photo taken from the website of the Miguel Covarrubias collection at UDLAP

▲ The dancer and painter with a tangle on her head. Photo taken from the Miguel Covarrubias collection website at UDLAP.

▲ Rosa Rolanda and Covarrubias in a mock boat. Photo taken from the Miguel Covarrubias collection website at UDLAP.

▲ Rolanda poses for Edward Weston's camera. Photo taken from the Miguel Covarrubias collection website at UDLAP.

Merry Macmasters

La Jornada Newspaper, Tuesday, May 6, 2025, p. 3

The University of the Americas Puebla (UDLAP) houses a comprehensive archive of Miguel Covarrubias (1904-1957), consisting of approximately 30,000 original documents from the cartoonist, illustrator, researcher, and anthropologist, as well as from his first wife, the dancer, photographer, and painter Rosa Rolanda (1898-1970). These include sketches, images, clippings, magazines, letters, notebooks, and diaries. Ninety-six files have been digitized online, with a total of 5,132 images.

Among the archive's gems are photographs taken of the couple by figures such as Nickolas Muray, Edward Weston, and Man Ray. Photos that later featured contemporary artists such as Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Dolores del Río, and Mario Moreno Cantinflas. Photos that, for example, Leo Mátiz took specifically of Kahlo.

María del Refugio Paisano Rodríguez, head of Archives and Special Collections at the UDLAP Library, highlights a letter written by Kahlo to the couple, signed: "Frida, la popular

." In the undated letter, written in Spanish and English, the painter, who looked after Rosa's dog during a trip the couple took to the United States, says she feels bored and that there is no gossip to share

.

El Chamaco, as Miguel Covarrubias was nicknamed, left his archive to Rosa Rolanda upon his death, who, in turn, donated it to the Jalisco architect Luis Barragán, with whom the couple had a close friendship, notes Paisano Rodríguez. Part of the archive was first donated to the Benjamín Franklin Library. According to the specialist, in 1977, through Dr. Kirkpatrick, a person who was already at UDLAP

, the archive was donated to the institution, which included a collection of books.

According to Paisano Rodríguez, the archive arrived in sealed cardboard boxes, to which no one had access, filled with folders, each with the name of its contents, which were respected. In other words, the archive was organized by folders. It wasn't until 1992 that the archive was moved to a room once called Porfirio Díaz; then, its organization began. Many of the folders were in poor condition and were replaced. An inventory was also made of each item, including its respective number.

This is a kind of tool for both organizing and consulting materials

, Paisano Rodríguez points out. Some of the documents, for example, said "Bali dances"

; however, sometimes they contained materials that had nothing to do with the folder title. The search was then made for a folder that was related, or meaningful, to the image in question. Once the inventory and catalog were complete, the most relevant material was selected for digitization

.

The most consulted collection

Work is still being done on the documentation for each folder because, when digitized, a description must be included. It's not just the image. The title, author, subject, and a description of the contents are missing

. What required the most care were the photographs, because most of them were silver gelatin prints.

According to the expert, of all the archives held at UDLAP, Miguel Covarrubias's is the most frequently consulted, both by students and specialists in this artist. It is in high demand, especially in the gallery

, she notes. In terms of the quantity of materials, it is only surpassed by the archive of the historian, ethnologist, and anthropologist Wigberto Jiménez Moreno, also held at UDLAP.

For Paisano Rodríguez, the Covarrubias archive is a gem

, containing unique and unrepeatable material that reflects the skill of a singular character who did not have academic studies, but who became one of the most significant artists that Mexico has had

.

He was a Mexican who brought his country's culture to other parts of the world through something as simple as a pencil. With a stroke of a pen, he was able to introduce the world to the cultural richness of Mexico and other nations, through something as enjoyable and easy to understand as a sketch or a caricature

.

Currently, the Archives and Special Collections services are temporarily suspended due to major renovations to the library building. These works are expected to be completed by January 2026. The Covarrubias archive can be viewed at the following link: https://catarina.udlap.mx/xmLibris/projects/covarrubias/

jornada