Under the rules of Doctor Luizinho

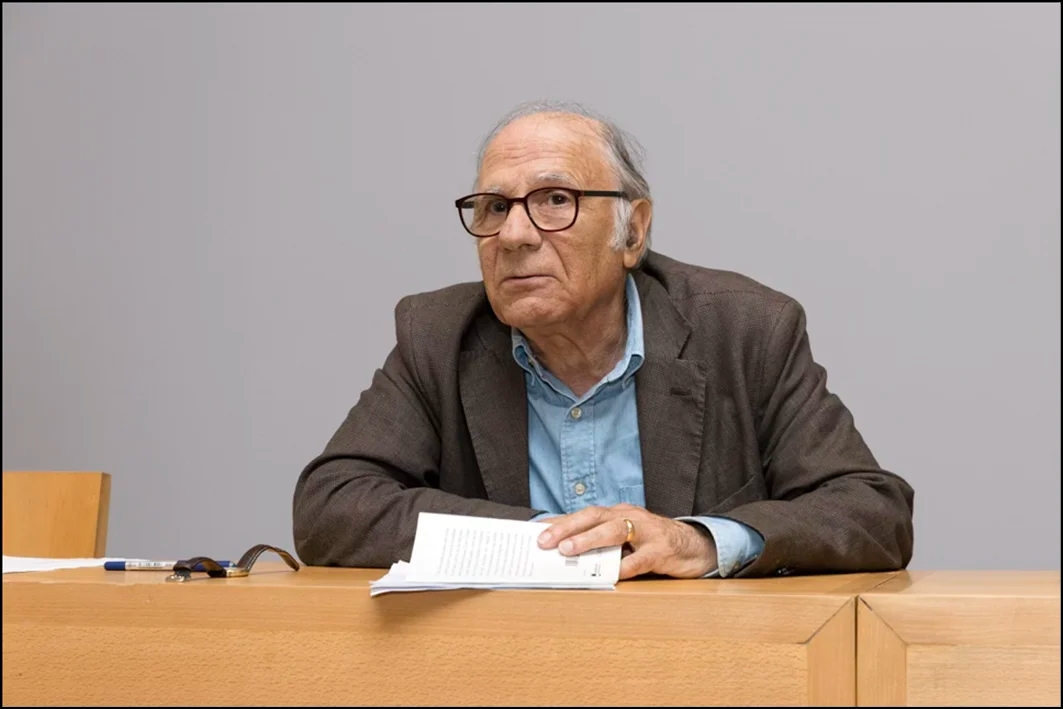

A name unknown in the audiovisual sector until two weeks ago has suddenly become the main driving force behind the bill regulating streaming services in the country: Doctor Luizinho, called "doctor" because he is, in fact, a physician, and a federal deputy elected from Rio de Janeiro.

The leader of the Progressives' bloc in the Chamber of Deputies, the congressman managed, on Tuesday the 4th, by 330 votes in favor, 118 against and 3 abstentions, to approve Bill 8,889, whose process dates back to 2017. The following day, in the afternoon, the amendments were voted on. Now, the text goes to the Senate.

The project involves more than 1 billion reais and targets big tech companies, video-on-demand (VoD) platforms, and online broadcasting services. The new resources are primarily intended for the production of Brazilian audiovisual content.

When it first came under discussion eight years ago, the law aimed to obligate foreign companies offering subscription services, such as Netflix and Prime Video, to include more Brazilian films and series in their catalogs and contribute to the production of independent national content.

The tax in question is the Contribution for the Development of the National Film Industry (Condecine), established 25 years ago and paid by different segments of the audiovisual industry and by telecommunications companies. Contrary to what has often been reported, the platforms do not refuse to pay this tax.

Their initial dispute revolved around how and how much to pay – what is known, in jargon, as dosimetry. Gradually, however, these companies began to argue that if they should collect Condecine, then content-sharing services like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram should too.

From then on, the main obstacles to projects dealing with this issue began to come primarily from big tech companies. Although much has been said about the VoD lobby throughout the process, Bill 8,889 ended up highlighting the power of big tech companies in the dispute.

The project's progress highlights the new power dynamics that have shifted from broadcast television to big tech companies.

While VoD services were created to produce and acquire films and series, charging for them, sharing platforms are based on user-generated content – which includes both those who post videos of kittens and so-called creators, professional content producers.

While these are distinct business models, we see Globo producing dramas in vertical format, with very short episodes, for TikTok, and Instagram announcing a future app for smart TVs.

If Dr. Luizinho's project touched on the crucial point of regulation, it's because, in its first version, the text stipulated that sharing platforms could reinvest part of the Condecine (a Brazilian film revenue source) in content produced by creators – something unprecedented in previous versions.

Could he, then, have been the first to actually compromise with the representatives of the big tech companies? Historically, broadcasting had power in Congress because many parliamentarians held concessions and because television was capable of building and destroying reputations.

Today, some of that power has migrated to social media, not only because the companies that control them are among the largest in the world, but because they are part of the political machinery. Many parliamentarians are, in fact, influencers.

As one of the project's organizers, advocating for independent production, stated, "Netflix doesn't have a parliamentary group and doesn't have the power to disrupt the life of a congressman." Dr. Luizinho seems to have understood this better than those who preceded him in drafting the bills.

The newly approved regulation derives, in particular, from three texts: that of Senator Eduardo Gomes (PL–TO), from 2023; that of Representative André Figueiredo (PDT–CE), from 2024; and, finally, the report by Representative Jandira Feghali (PCdoB–RJ), from 2025.

Gomes's project was eventually approved, but Jandira's failed to move forward. In addition to obstruction in Congress, there was the spread of fake news, such as claims that the government wanted to interfere with content or that subscriptions to services would increase – even though none of the companies directly linked to the sector had stated this.

At one point, the Speaker of the House, Hugo Motta (Republicanos–PB), stated, both to the Ministry of Culture (MinC) – responsible for government coordination – and to representatives of the different sectors impacted by the regulation, that he would appoint a third rapporteur.

It was, however, with great surprise that, on October 27th, the Ministry of Culture and the sector received Dr. Luizinho's text. The project was instantly criticized by the government, by Strima – an entity that brings together paid video-on-demand services such as Netflix, HBO, and Globoplay – and by some independent Brazilian producers. Until last week, the unions representing the industrial side of the audiovisual sector were the only ones to support it.

Format. Part of the quota may be fulfilled with works produced by companies linked to broadcasting, i.e., with soap operas like Vale Tudo, for example – Image: Social Networks/TV Globo

Format. Part of the quota may be fulfilled with works produced by companies linked to broadcasting, i.e., with soap operas like Vale Tudo, for example – Image: Social Networks/TV Globo

The text seemed doomed to failure. But that's not what happened. On Tuesday morning, negotiations began: the congressman posted a photo on his Instagram stories showing him alongside government officials, representatives from the National Film Agency (Ancine), and Paula Lavigne. From then on, it was a back-and-forth that lasted until late at night.

Part of the conversation in the Chamber was along the lines that, if certain points considered essential by the Ministry of Culture were not met, the government's bloc could vote against them – even though regulation is a flagship policy of Lula's in the cultural area.

Some of Luizinho's interlocutors told CartaCapital that his motto was: "I have no commitment to anyone." The congressman was allegedly chosen by Motta because he was one of the "five" strongest members of the Chamber capable of "solving the problem."

The bill, as presented, was itself a problem. On one hand, there was the reaction of those who would be taxed, and on the other, the displeasure of part of the independent production sector, which considered the contribution percentages to be low and the wording to benefit large production companies.

Although the congressman initially appeared reactive, he ultimately accepted so many suggestions that he created what some consider to be an overlap of rules.

In summary, the project establishes the Condecine-Streaming tax, which will be levied on the gross revenue of streaming platforms and has progressive rates that vary according to revenue. VoD platforms will pay up to 4% and may receive discounts if they invest in the production of national content.

This 4% is less than Brazilian producers had hoped for and more than the platforms had agreed to pay – 3%. Of the total, 60% can be invested directly by the platforms in projects of their choice, and 40% will go to the Audiovisual Sector Fund (FSA), managed by Ancine. There are a number of exemptions and restrictions foreseen.

The bill, considered a victory by the government and independent producers, now goes to the Senate.

For content sharing services, the maximum tax rate was set at 0.8%. Initially, the text stipulated 2%, but, as mentioned before, authorized that part of this be directed to YouTubers and influencers. A new addition to the text, made during the voting process, is that creators will be able to access the FSA (Fund for Access to Services).

The bill also establishes a quota for VoD: providers must offer at least 10% Brazilian content in their catalogs. Foreign services requested a 7% quota and wanted to be able to comply, at least partially, with their original content – Brazilian productions for which they hold the patrimonial rights. They achieved neither.

Part of the quota could, however, be fulfilled with works produced by broadcasting companies, i.e., soap operas, for example. Broadcasting companies also managed, at the last minute, to obtain a 25% discount on the 4% Condecine payment. This arrangement was made by TV Record, together with the opposition bloc.

Although it ultimately pleased no one 100%, Bill 8.899/2017 was understood by the Brazilian government and producers as a victory, and by the major VoD services as a defeat. In addition to injecting a huge volume of resources into the audiovisual sector, the bill made explicit the new power dynamics both in Congress and in society.

Published in issue no. 1387 of CartaCapital , on November 12, 2025.

This text appears in the print edition of CartaCapital under the title 'Under the rules of Doctor Luizinho'.

CartaCapital