Three years on, Ukraine's extinction nightmare has returned

Kyiv no longer looks like a city at war in the way that it was three years ago. The shops are open and commuters get delayed in traffic jams on their way to work. But in the days since 12 February this year when US President Donald Trump rang Russia's Vladimir Putin to send a 90-minute political embrace from the White House to the Kremlin, 2022's old nightmares of national extinction have returned. Ukrainians used to get angry about the way that President Joe Biden held back weapons systems and restricted the way Ukraine used the ones that arrived here. Even so, they knew whose side he was on.

Instead, Donald Trump has delivered a stream of exaggeration, half-truths and outright lies about the war that echo the views of President Putin. They include his dismissal of Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky as a dictator who does not deserve a seat at the table when America and Russia decide the future of his country. The biggest lie Trump has told is that Ukraine started the war.

Trump's negotiating strategy is to offer concessions even before serious talks have started. Instead of putting pressure on the country that broke international law by invading its neighbour, leading to huge destruction and hundreds of thousands of dead and wounded, he has turned on Ukraine.

His public statements have offered Russia important concessions, declaring that Ukraine will not join Nato and accepting that it will keep at least some of the land it seized by force. Vladimir Putin's record shows he respects strength. He regards concessions as a sign of weakness.

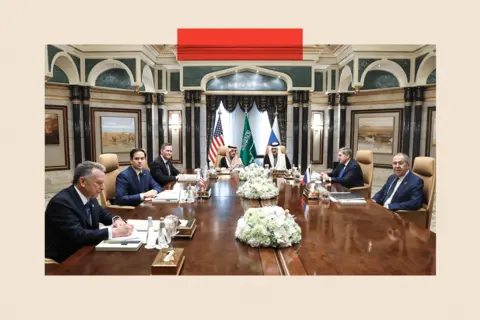

He has not budged from a demand for even more Ukrainian land than his men now occupy. Immediately after the first talks, held in Saudi Arabia, between Russia and the US since the 2022 invasion, Putin's foreign minister Sergei Lavrov repeated his demand that no Nato troops would be allowed into Ukraine to provide security guarantees.

A veteran European diplomat who has dealt with the Russians and the Americans told me that when the grizzled, highly experienced Lavrov met Trump's novice Secretary of State Marco Rubio "he would have eaten him like a soft-boiled egg."

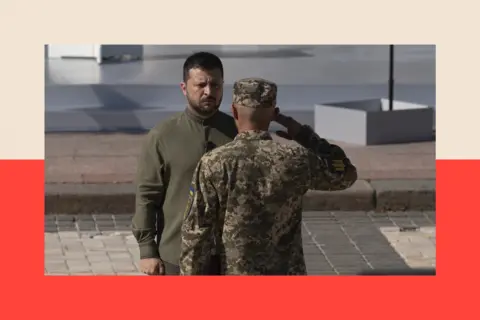

A few days ago, as Trump threw more insults at Ukraine's president, I went to the heavily guarded government quarter in Kyiv to meet Ihor Brusylo, who is a senior adviser to Volodymyr Zelensky and deputy head of his office. Brusylo acknowledged how much pressure Trump is putting on them.

"It's very, very tough. These are very hard, challenging times," Brusylo said. "I wouldn't say that now it's easier than it was in 2022. It's like you live it all over again."

Brusylo said Ukrainians, and their president, were as determined to fight to stay independent as they had been in 2022.

"We're a sovereign country. We are part of Europe, and we will remain so."

In the weeks after Vladimir Putin ordered the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the sound of battle on the edge of Kyiv echoed around streets that were almost empty. Checkpoints and barricades, walls of sandbags and tank traps welded from steel girders were rushed out onto Kyiv's broad boulevards. At the railway station, fifty thousand civilians a day, mostly women and children, were boarding trains going west, away from the Russians.

The platforms were packed and every time a train pulled in, came another surge of panic as people pushed and shoved to get on. In those freezing days, in bitter wind and flurries of snow, it felt as if the colours of the 21st century were fading into an old monochrome newsreel that Europeans had believed until then was safely consigned to the vaults of history.

President Zelensky, in Joe Biden's words, "didn't want to hear" American warnings that an invasion was imminent. Putin rattling a Russian sabre was one thing. A full-scale invasion, with tens of thousands of troops and columns of armour, surely belonged in the past.

Putin believed Russia's mighty and modernised army would make quick work of its obstinate, independent neighbour and its recalcitrant president. Ukraine's western allies also thought Russia would win quickly. On television news channels, retired generals talked about smuggling in light weapons to arm an insurgency while the west imposed sanctions and hoped for the best.

As Russian troops massed on Ukraine's borders, Germany delivered 5,000 ballistic combat helmets instead of offensive weapons. Vitali Klitschko, the mayor of Kyiv and once heavyweight boxing champion of the world, complained to a German newspaper that it was "a joke… What kind of support will Germany send next, pillows?"

Zelensky turned down any idea of leaving his capital to form a government in exile. He abandoned his presidential dark suit for military attire, and in videos and on social media told Ukrainians he would fight alongside them.

Ukraine defeated the Russian thrust towards the capital. Once the Ukrainians had demonstrated that they could fight well, the attitude of the Americans and Europeans changed. Arms supplies increased.

"Putin's mistake was that he prepared for a parade not a war" a senior Ukrainian official recalled, speaking on condition of anonymity. "He didn't think Ukraine would fight. He thought they would be welcomed with speeches and flowers."

On 29 March 2022, the Russians retreated from Kyiv. Hours after they left, we drove, nervously, into the chaotic, damaged landscape of Kyiv's satellite towns, Irpin, Bucha and Hostomel. On the roads the Russians had hoped to use for a triumphant entry into Kyiv, I saw bodies of civilians left where they were killed. Charred tyres were stacked around some of them, failed attempts to burn the evidence of war crimes.

Survivors spoke of the brutality of the Russian occupiers. A woman showed me the grave where she had buried her son single-handed after he was casually shot dead as he crossed a road. Russian soldiers threw her out of her house. In the garden, they left piles of empty bottles of vodka, whisky and gin that they had looted and drunk. Hastily abandoned Russian encampments in the forests near the roads were choked with rubbish their soldiers had discarded over the weeks of occupation.

Professional, disciplined armies do not eat and sleep next to rotting piles of their own refuse.

Three years on, the war has changed. Although Kyiv has revived, it still has nightly alerts as its air defences detect incoming Russian missiles and drones. The war is closer, and more deadly, along the front line, more than 1,000 kilometres long, that runs from the northern border with Russia and then east and south down to the Black Sea. It is lined with destroyed, almost deserted villages and towns. To the east, in what was Kyiv's industrial heartland of Donetsk and Luhansk, Russian forces grind forward slowly, at a huge cost in men and machines.

Last August, Ukraine sent troops into Russia, capturing a pocket of land across the border in Kursk. They are still there, fighting for land that Zelensky hopes to use as a bargaining chip.

Along the border with Kursk, in the snow-covered forests of north-eastern Ukraine, the geopolitical storm set off by Donald Trump is still not much more than a menacing, distant rumble. It will get here, especially if the US president follows up his harsh and mocking verbal attacks on president Zelensky with a final end to military aid and intelligence-sharing, and even worse from Ukraine's perspective, an attempt to impose a peace deal that favours Russia.

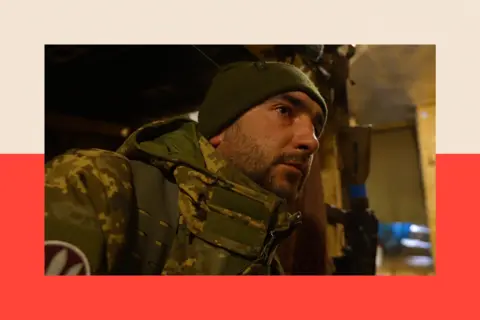

For now, the rhythm built up in three years of war goes on, and the forest could be a throwback to the blood-soaked twentieth century. Fighting men move silently through the trees, along trenches and into bunkers dug deep into the frozen earth. In stretches of open ground, anti-tank defences made of concrete and steel stud the fields.

The 21st century is more present in the dry and warm underground bunkers. Generators and solar panels power laptops and screens linked to the outside world, and bring in the news feeds.

Just because bad news arrives doesn't mean that the soldiers look at it. In a deep dug-out lined with bunks made of rough planks from the local sawmill, with nails hammered into the timber to hang weapons and winter uniforms, Evhen, a 30-year-old corporal said he had more urgent matters to think about – his men and the wife and two small children he left at home when he joined up, ten months ago.

That's a long time on the front line in Kursk. He looks and sounds like a combat veteran. He has faced the North Koreans who have been sent to join the battle there by their leader, Putin's ally, Kim Jong Un.

"Koreans fight till the end. Even if he is injured and you come to him, he might just blow himself up to take more of us with him."

All the soldiers we interviewed asked to be referred to by first names for their own security. Evhen seemed relaxed about fighting on without the Americans.

"Help is not something that can last forever. We have it today, we don't have it tomorrow."

Ukraine, he said, was making many more of its own weapons. That's true, especially when it comes to attack drones, but the US still supplies sophisticated systems that have damaged the Russians badly.

Many of the volunteers who took up arms three years ago have either been killed, maimed, or are too exhausted to fight any more. One of Ukraine's most bitter fault lines runs between those who fight and those who bribe their way out of military service. Evhen said they were better off without them.

"It is better for them to pay not to fight than to come here and run away, tripping us up. It doesn't bother me much. If they came here, they'd just scarper… they're deserters."

War strips away surplus thought. The stakes are straightforward for soldiers preparing to return to the battle in Kursk. Mykola, who commands a company of airborne assault troops, spoke affectionately about the capabilities of their Stryker armoured vehicles, supplied by the Americans.

"Kursk" he says, "shows the enemy, a nuclear weapons state, that a non-nuclear power with a smaller population and a smaller army can come in, capture land and the Russians have been able to do very little about it."

Putin's objectives, he said, were clear.

"His task is to seize all of Ukraine, change its legal status, and change the president and government. He wants to destroy our political system and to make Ukraine his vassal state."

He laughed when I asked whether the Americans and others should trust Vladimir Putin.

"No! I don't have enough fingers to count how many times Putin lied. To everyone! To the Russians, and to us, and to Western partners. He lied to everyone."

At a volunteer centre in Kyiv in the first days after the invasion, I met two young students, Maxsym Lutsyk, 19, and Dmytro Kisilenko, 18, who were signing up to fight.

When they lined up alongside men old enough to be their fathers as well as other teenage recruits, they carried camping gear and could have been friends off to a festival, except for their assault rifles. At the time, I wrote "18 and 19-year-old lads have always gone off to war. I thought in Europe we'd got past that." A few weeks later, Maxsym and Dmytro were in uniform and manning a checkpoint just behind the Kyiv front line, still students joking about their parents.

Both fought in the battle of Kyiv. Dmytro chose to leave the army, his right as a student volunteer, when the fight switched to the east. He is preparing to fight again if necessary, training to be an officer at the National Military University. Maxsym stayed in uniform, serving in the front line in the east for more than two years. Now he is an officer working in military intelligence.

I have stayed in touch with them as, like millions of other young people here, war shapes their adult lives in ways they never expected. Trump's move towards Moscow makes them feel almost as if they have to start again.

"We mobilised," Dmytro says. "We mobilised our resources, our people, and I think it's time that we repeat it once again."

Unlike the men in the forest on the Kursk border, they follow the news. Donald Trump's diplomatic and strategic bombshells, starting at the Munich security conference only 10 days ago, reminds them of the infamous deal Britain's prime minister Neville Chamberlain made at Munich in 1938, forcing Czechoslovakia to capitulate to the demands made by Adolf Hitler.

"It's similar," Maxsym said. "The West gives an aggressor an opportunity to occupy some territories. The West is making a deal with the aggressor, with the United States in the role of Great Britain."

"It's a very dangerous moment for the entire world, not only for Ukraine," Maxsym went on. "We can see that Europe is starting to wake up… but if they wanted to be ready for the war, they should [have] begun a few years ago."

Dmytro agreed about the dangers ahead.

"I think that Donald Trump wants to become like a new Neville Chamberlain… Mr. Trump should be more focused on becoming more like Winston Churchill."

If you're a real estate developer, as Donald Trump was before he went into reality TV and then presidential politics, demolition makes money. Acquire a property, tear it down, rebuild and win. The trouble with that strategy in foreign policy is that sovereignty and independence don't have a price tag. Trump boasts he puts America first, but he is not prepared to accept that non-Americans can feel the same about their own countries.

Since Trump was sworn in for the second time as president of the United States, he has been swinging the wrecking ball. He sent Elon Musk into the federal government to recoup billions of dollars he claims are being stolen or wasted. Abroad, Trump the demolition man has set about the assumptions that underpin the eighty year alliance between the US and European democracies.

Donald Trump is unpredictable, but much of what he is doing he has talked about for years. He is not the first American president to resent the way its European allies have saved money by sheltering behind the US defence budget. The phrase used by his defence secretary Pete Hegseth to his Nato partners, that "President Trump will not allow anyone to turn Uncle Sam into Uncle Sucker" was a conscious reference back to President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

A US government document from 4 November 1959 records his frustration. It says: "The President said that for five years he has been urging the State Department to put the facts of life before the Europeans He thinks the Europeans are close to 'making a sucker out of Uncle Sam.'"

Trump wants payback. He demanded half a trillion dollars of mineral rights from Ukraine. Zelensky turned that deal down, saying he couldn't sell his country. He wants security guarantees in exchange for any concessions.

In private, European politicians and diplomats recognise that, with Joe Biden, they gave Ukraine enough military and financial support not to lose to Russia, but never enough to win. The argument for more of the same is that Russia, weakened by sanctions and drained of manpower as its generals squander their men's lives, will eventually lose a war of attrition. That is far from certain.

Wars usually end with agreements. Germany's unconditional surrender in 1945 was a rarity. The complaint against Trump is that he has no real plan, so he has followed a gut instinct to get closer to Vladimir Putin, a man he admires. Trump seems to believe that strong leaders from the most powerful states can bend the world into the shape they want. The concessions Trump has already offered to Putin reinforce the idea that his top priority is normalising relations with Russia.

A more credible plan would have to include a way to make Putin drop ideas that are lodged deep in his geostrategic DNA. One of the strongest is that Ukraine's sovereignty must be broken and control of the country returned to the Kremlin, as it was in Soviet times and before that in the empire of Russia's Czars.

It is hard to see how that happens. The idea is as unlikely as Ukraine surrendering its independence to Moscow. Europe's security is being turned upside down by the war in Ukraine. No wonder its leaders are so badly rattled by all they have heard and seen this month.

Their challenge is to find ways to avoid their young people being forced into the unexpected world of war that has enveloped Maxsym Lutsyk, the 22-year-old Ukrainian combat veteran.

"Everyone changed, and I have changed. I think that every Ukrainian matured during these three years. Everyone who entered the military and everyone who was fighting for such a long time drastically changed."

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

BBC