Is Creativity Dead? Susan Orlean Knows Better

I’ve called Susan Orlean to discuss creativity, but I can’t stop staring at the poster-size playing card propped up behind her chair. The Queen of Hearts grimaces back at me while the legendary New Yorker staff writer—and author of nine books, the latest of which is Joyride, out October 14—basks in her glass room of curiosities. Her iconic red hair and berry-colored lipstick stand in stark contrast to the riot of vegetation behind her, kept at bay only by the floor-to-ceiling windows that separate her office from the wilderness outside. On the desk to her right are a book, a downy teddy bear, and a typewriter the shade of key lime pie.

I’ve prepared for where this conversation will take us: I have, of course, read Orlean’s work, scratching notes in the margins of her books and preparing my interview questions, all centering on a thought that’s been rattling around my head lately: Is creativity a matter of urgency? Or is that the self-important notion of, say, a self-proclaimed creative? Still, when Orlean and I log off, I find myself distracted not by this question but by the contents of her house. All I’ve seen of it is the office, the teddy bear, the glass. I want to see more.

I click on several articles about the house—designed by the Austrian-born architect Rudolph Schindler in 1946 and hovering on a hilltop over the San Fernando Valley like a guardian angel—and eventually land on a post from Orlean’s Substack newsletter, Wordy Bird. I dig deeper, scrolling through the archives to learn her thoughts on clothes, earthquakes, beauty, and the smell of New York City (a “pizza-grease-and-roach-spray kind of bouquet”). As my browser strains under the demands of my 30-plus open tabs, I realize I’ve unintentionally completed a step in Orlean’s creative process, one she calls “the oblique angle”: When a person approaches the question at hand from “related but tangential places,” tumbling down a rabbit hole. Orlean explains, “You may not use any of that material, but it is where you begin thinking more creatively, more imaginatively, more originally.” And that, she argues, is when the most important work begins.

Joyride is Orlean’s first memoir and joins a growing canon of essay collections, craft books, self-improvement guides, and autobiographies that encourage a certain attitude toward creativity: not as obsolete in the face of evolving technologies, nor as an escape from more “important” matters—but as a necessary tool to face them both. The hunger for these books is no new phenomenon. Perhaps the most obvious example of their continued relevance is the renewed popularity of Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way. The 1992 treatise and workbook, which outlines exercises for sparking creativity—and draws connections between the creative and the divine—took off among those yearning for motivation in a fragmented, post-quarantine world. (Grammy-winning musician Doechii was one of several high-profile figures to attempt the book’s “morning pages,” documenting her progress on YouTube.) In a world that prioritizes optimization over discovery and the artificial over the human, the hunger for creativity—and the urgency around it—only seems to be growing.

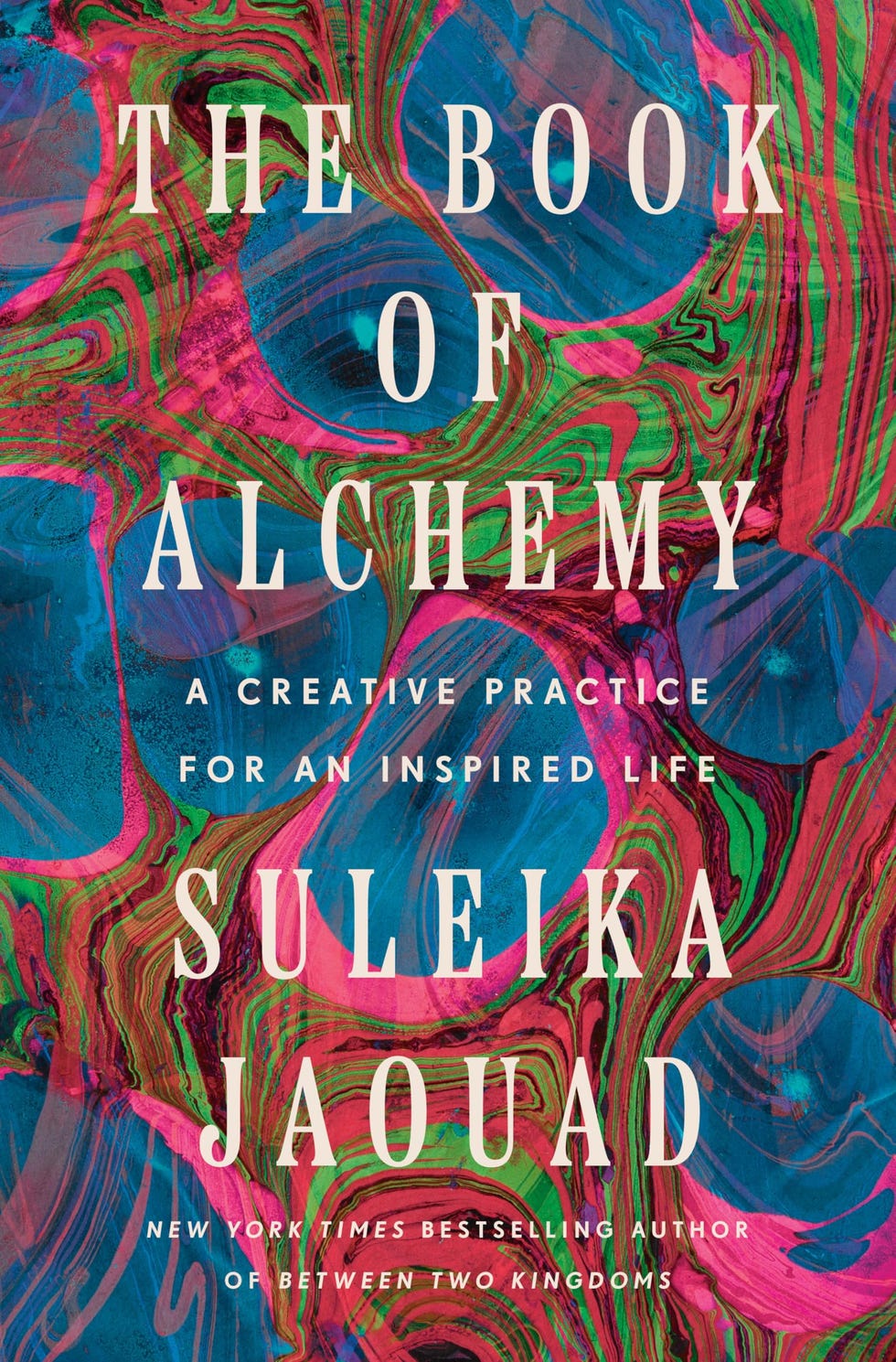

In 2025 alone, a whole stack of books on (or tangential to) this school of thought has been flooding the shelves. January welcomed the social scientist Martha Beck’s Beyond Anxiety: Curiosity, Creativity, and Finding Your Life’s Purpose; in the spring came Maggie Smith’s Dear Writer: Pep Talks and Practical Advice for the Creative Life and Suleika Jaouad’s The Book of Alchemy: A Creative Practice for an Inspired Life; artist and author Sally Mann’s Art Work: On the Creative Life arrived in September; Sue Monk Kidd’s Writing Creativity and Soul is out this month; and GG Renee Hill’s Story Work: Field Notes on Self-Discovery and Reclaiming Your Narrative is set to drop in November. (And this is just a small sampling of the titles on offer.) These books vary in their focus, but as in Orlean’s Joyride, the takeaway often has as much to do with the art of living as the art of writing. And when the art of living feels perhaps trickier than ever, creativity holds practical appeal.

“There’s a little bit of a scolding attitude that says, ‘Oh, creativity is something you do if you’ve got the means and the luxury of time,’” Orlean tells me. She shrugs, shaking her head. “I would disagree. The act of engaging is available to everybody, and it’s not about having the financial freedom to screw around. Creativity is the most universally available commodity. It’s about taking advantage of what’s around you.” It’s not the sole terrain of writers, nor even of “creatives,” she says. It’s a way of “engaging in life with an openness and curiosity that pushes beyond the conventional.”

Joyride is a memoir, but it is also a tribute to this philosophy, the driving force in Orlean’s life. Compiled mostly in chronological order—the first of her books to do so, Orlean adds—the narrative follows Orlean’s journey from her childhood in Cleveland to her first journalism jobs in Portland, Oregon, and Boston to her role at The New Yorker. We learn about her parents; about the breakdown of her first marriage; about her son and her second husband; and about her infamous 2020 drunken Twitter tirade, after which she anointed herself the “patron saint of pandemic drinking.” Along the way, she unpacks the stories behind her major stories: “The American Man at Age Ten” in Esquire; “Be a Joke Unto Yourself” in The Village Voice; and her books, including Saturday Night, Rin Tin Tin, The Library Book, and The Orchid Thief, which was transformed into the acclaimed film Adaptation in 2002. Although these peeks behind the curtain are interesting on their own merits, it’s Orlean’s sense of mission that propels the reader along.

“The act of engaging is available to everybody, and it’s not about having the financial freedom to screw around. Creativity is the most universally available commodity.”

“Writing is the most meaningful thing I’ve ever done,” she says in the early pages of Joyride. “I wanted to be a writer because I wanted to show that any life closely examined is complex and exceptional and can embody both the heroic and the plain.”

“Close examination” is perhaps the sole common denominator across Orlean’s wide-ranging body of work, and it’s such examination she fears might be lost in our over-optimized modern era. She admits that Joyride succumbs to nostalgia for the halcyon days of magazine journalism, in which a reporter like herself could spend days circling the mere scent of a story. Over the decades of Orlean’s career, time and financial constraints have squeezed once-ample reporting resources. At the same time, tech—smartphones, social media, artificial intelligence—has transformed our information ecosystem, making our steps within it less certain. How, then, do we continue to explore? Orlean wonders. And, equally important, how do we remind all people (not only “creatives”) that exploration is a matter of import? Even urgency?

Orlean on the runway at the Susan Alexandra x Rachel Antonoff Dog Show during New York Fashion Week in September 2025.

Orlean is not a technophobe, she says, nor an anti-AI purist. She uses ChatGPT, though mainly for “chores,” like finding a local appliance technician or planning a trip. She does not use generative AI for story research or in any of her writing. She understands the technology’s capacities well enough to recognize its power to remove humans from primary sources, the journalist’s equivalent of “touching grass.” “We’re in this inflection point where the way we were creative in the past, we have to come up with a new way,” Orlean says. “I refuse to believe that we are now going to be in an era of no creativity.”

Her solution, then, is to treat creativity not as a luxury, nor as this “wispy, unmanageable thing that you don’t dare think about because you might bring it crashing down to earth.” Creativity is a human necessity, she believes, and thus should be treated as practical—and given a pragmatic approach. “The best thing you can do is to be analytical and even mechanical about it,” she recommends. She sets a daily word count when she’s working on a project, which she likens to exercise: “When I was a runner, I would never just ‘go for a run.’ I would say, ‘I’m going to do eight miles.’ And at the four-mile mark, I would think, ‘I’m halfway done.’ I couldn’t have done it without that framework.” She has the same approach to her creative process: “I punch the clock, and then I can be as free as I want to be.”

Although books like The Artist’s Way, The Book of Alchemy, and Art Work might or might not phrase their advice in the same way, their arguments are similar: Creativity is an action, one that works best as part of a routine. The tips inside these books have as much to do with functionality as philosophy: Locate a special spot in which to work. Fill your space with curiosities—books, mementos, maybe a life-size playing card. Write ideas down, on actual paper. Set a timer or a deadline. Ask questions. Listen. Engage. Do the same thing tomorrow, and then the next day, and the day after that. Treat the creative practice as precious, necessary, even sacred—because it is. “People often make the mistake of believing that having a process will deflate their creativity,” Orlean says. “To me, process liberates creativity.”

A version of this story appears in the September 2025 issue of ELLE.

elle