Bad Dojo: Tiger Schulmann Didn’t Get to Be America’s No. 1 Karate Kingpin Without Busting a Few Faces

The New Jersey Convention and Expo Center is nestled among a series of fading industrial parks just off I-95. Most weekends, it’s overrun with model-train enthusiasts, hot-tub salesmen, and fly fishermen. But on a sunny day in December, the cavernous hall’s permascent of pretzel grease is cut with a new odor: the tangy smell of cowhide gloves connecting with flesh. For today, Daniel “Tiger” Schulmann, the strip-mall karate kingpin of America, is holding his semiannual Challenge of Champions.

Hundreds of kids in headgear, some as young as five, whale on one another as their parents stalk the sidelines, urging them on in a dozen languages. Ringside scoreboards glow with names like Menendez, Mohammed, Wang, and Gelashvili—a far cry from the villainous dojo full of bleach-blond teens in The Karate Kid to which this franchise is sometimes compared.

In the far corner, away from the kids, grown men uncork body shots that send a shiver all the way down into my testicles. And there, on the sideline, is the man himself. Before I can procrastinate with another trip to the hot dog stand, an instructor takes me by the arm and presents me to Tiger Schulmann. After weeks of back-and-forth, I’m finally meeting him in person. Surrounded by muscle-bound lieutenants and former UFC fighters, he considers me with suspicion. “You know more than I do about my company,” he says. “It scares me.”

As we talk, Schulmann taps my shoulder and chest, almost like he’s range-finding, in case he decides to flatten me with a jab-cross combo. Only the steady stream of children provides reassurance, as they gather around him shouting, “Shihan! Shihan!”—or “teacher of teachers”—and clamor for selfies.

Tiger Schulmann’s martial-arts empire is vast. He has fifty-four schools across the Northeast, where his senseis turn ninety-eight-pound weaklings into warriors for a few thousand dollars a pop. The franchise grosses more than $35 million a year, and Schulmann himself has made a fortune. At sixty-two, he’s still got that intimidating aura, flinty stare—and the eight-pack too. But most importantly, he’s got respect. Schulmann has put so many protégés into the octagon that no less than Joe Rogan has toasted his success in the Ultimate Fighting Championship.

Mention Tiger Schulmann’s Karate to a millennial from the New York–New Jersey area and witness a blast of nostalgia. Saturday-morning cartoons in the 1990s and 2000s were flooded with his ads: Kids intimidate bullies and kick monsters out of bedroom windows. A Tina Turner sound-alike wails, “Whoa Tiiiiiger! Yeah, yeah, yeah! Tiiiiiger!” A pitchman exhorts parents to call 1-800-52-TIGER.

But behind the pressed white uniforms and kids’ birthday parties, Tiger Schulmann’s Karate was once a Wild West of broken bones and bruised egos, fortunes made and reputations squandered, where many of the hits were below the black belt. Schulmann invited the wrath of prosecutors and police, aggrieved former senseis, and keyboard ninjas who called him a “scumbag” and “scam artist.”

“It’s like they’ve combined the best of multilevel marketing and the Mafia,” says Sean Kelly, publisher of UnhappyFranchisee.com. A one-star Yelp review sums up his critics’ case: “THIS IS THE REAL-LIFE COBRA KAI!”

By the time we meet at the Challenge of Champions, Tiger Schulmann has already decided that I’m writing a hit piece. “If it’s going to be that,” he says, “write it without me.” But soon the bobbing and weaving switches into rope-a-dope. Schulmann can take the hits—and counterpunch too. He has a different story to tell if I will listen: how he forged a culture of discipline, personal growth, and honor—and defended it without apology. “You might even change your whole mind,” he says. “I’m gonna leave out all the bullshit.”

There is plenty to boast about. Ten fighters—all homegrown at his schools—that he placed in the UFC. The wayward young cousin he molded into a loving father and successful franchisee. The dozens of school owners—some netting up to $500,000 a year—who lead lives of meaning and purpose. Schulmann’s induction into the New Jersey Martial Arts Hall of Fame. The five hundred instructors, franchisees, and friends who recently raised a glass at the company’s fortieth-birthday party.

And those embittered former senseis? The dojo storming and stacks of cardboard boxes filled with litigation? “All those things only made me stronger,” Schulmann says. To his detractors, he has some advice: “You’re responsible for your own life. You’re responsible for what happens to you. Stop blaming other people. Stop being a wimp. Stop being a wuss about it.”

Indeed, you do not build America’s preeminent martial-arts franchise without breaking a few noses. “I don’t have any enemies,” he says, although that statement is one-sided. While the bitter feuds are in his rearview mirror, plenty of men still want a piece of him—financially and physically.

And Tiger Schulmann is ready for them. He’s been ready for more than half a century, ever since he learned at nine years old that raw power is the real currency in this life and everything else follows suit.

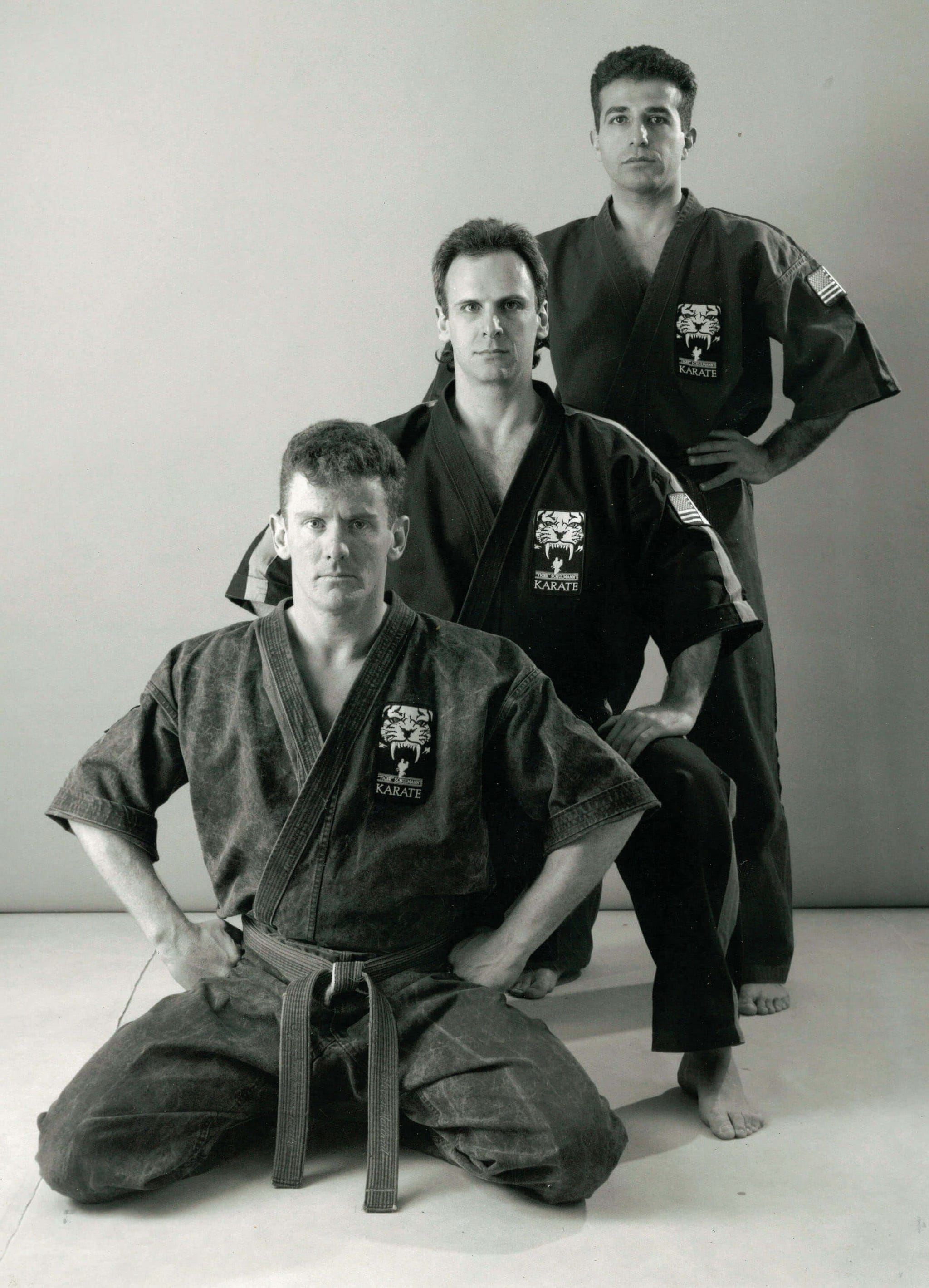

From front: Steven Holland kneeling; his sensei, Gary Hellman, behind him; and Tiger Schulmann standing, circa 1990.

The origin story is legend, told to prospective students, printed in karate magazines, plastered on the wall of the franchise’s New Jersey headquarters: One day in 1972, Schulmann’s older brother Ben crawled home from the bus stop after anti-Semitic bullies broke his leg.

It had been a long road for the Schulmann family to this small house in West Haverstraw, New York. His father, David, grew up in Berlin in the 1930s and fled the Nazis as a boy. His family made it all the way to Shanghai, just in time for the Japanese to lock them in an internment camp. Through a chain-link fence, little David watched the imperial army practice karate and then use those skills to rough up Chinese civilians. Seeing martial arts in action made a lasting impression on him.

David survived the war and made it to Israel, then Brooklyn. But a sense of helplessness continued. At their yeshiva, Conservative Jewish boys bullied Danny and his brothers. Then, on the way home through Borough Park, Italian and Irish kids shouted, “Fuckin’ Jews!” at them. They moved to Rockland County, where more anti-Semites awaited them. And now Ben was laid out with a broken leg.

Young Danny watched something in his father snap. That’s it, he declared. You’re learning karate. Soon, Danny’s whole extended family was mounting the steps of a rundown dojo, the warlike cries of Kiai! shaking the walls.

Danny Schulmann excelled. Martial arts was still a niche sport, and most dojos were side hustles for owners with day jobs. He studied a karate style called Kyokushin, or “the ultimate truth,” pioneered by a legendary shihan named Mas Oyama. (Oyama later became the inspiration for Ryu in the video game Street Fighter.) Schulmann, diminutive but feisty, earned the nickname “Tiger” for his speed, strength, and zodiac sign.

David Schulmann moved the family again, this time to Quakertown, Pennsylvania, where he used his life savings to buy a motel that they ran as a family business. New town. Same anti-Semites. The only other Jewish person was a pharmacist named Cohen with seven adopted Vietnamese kids. The motel was a rough place. Truck drivers and transients. Lots of hourly clients. Guests passed bad checks on the way in and stole TVs on the way out. Danny folded towels, unclogged toilets, and laid panel.

Schulmann was soon helping out in other ways. When he was seventeen, his mother shook him awake at 2:00 A.M. “They’re killing your father!” she cried. He bounded downstairs to find his father grappling with an armed robber. Schulmann kicked the intruder into a wall so hard he shit his pants, then subdued him in a chicken-wing arm hold until police arrived. “The Schulmanns lost nothing but some sleep,” the local newspaper concluded.

Schulmann began responding to perceived slights with violence. After a kid shouted, “Jew!” in the cafeteria, he slammed the bully’s head into a lunchroom table. (“That wasn’t one of the techniques we learned,” says Ron Schulmann, his younger brother, with a laugh.) Later, when a bus driver wrongly blamed Schulmann for misbehaving, he beat the driver so badly that he had to crawl into the school to get help. He was briefly expelled, saw a psychiatrist, and returned to graduate.

By then Schulmann was fighting competitively too, first in point matches and later in full-contact knockdown competitions. At an Alabama tournament, he went up against Y. Hioki, a fellow disciple of Mas Oyama. Schulmann had already clocked that Oyama favored Japanese fighters. He felt the judges at the tournament shared that bias. During the fight, Hioki kicked Schulmann in the groin without penalty. “If you do it again,” said Schulmann, “I’m going to knock you out.” When the match resumed, Hioki hit him in the balls again. Schulmann uncorked a left hook and knocked him out cold. The judges disqualified him. He left his second-place trophy in the gym and quit Oyama’s school for good.

Everyone told Schulmann there was no money in karate. It was a part-time job at best. His father disagreed. “This is America,” he said. “You can do what you want.” Schulmann opened a small dojo in Quakertown and called it United American Karate—a pointed rebuke of Mas Oyama and the Japanese. He would do it his way.

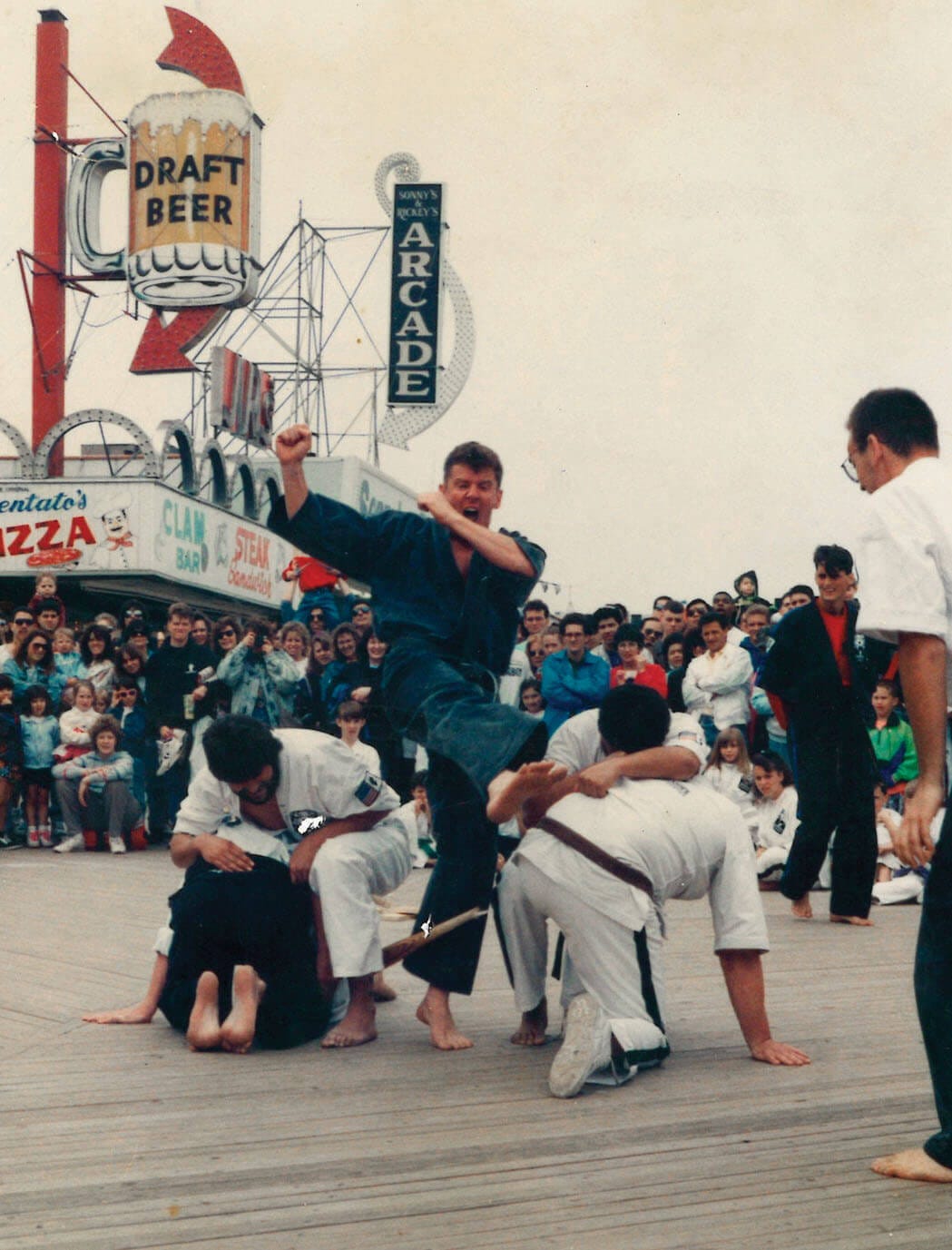

A group of Tiger Schulmann’s students doing a demonstration in Toms River, New Jersey, in 1990.

The year 1984 was an auspicious one to open a dojo. The Karate Kid made $91 million at the box office, and suburban kids began pouring into strip-mall dojos. A thriving under-eighteen market suddenly made martial arts a viable business.

Schulmann teamed up with Gary Hellman, a bouncer, and Shahrokh Mehrkar, another disaffected disciple of Mas Oyama. Mehrkar had fled Iran after the overthrow of the shah a few years earlier. He was a rough character, but Schulmann insists he didn’t yet know just how violent and turbulent he could be.

Together they recruited a crew of hungry young martial artists, many of them stuck in dead-end jobs. Steven Holland was a high school dropout and Marine veteran working as a corrections officer at the Rockland County jail, getting cups of piss thrown on him as he patrolled. He was a brawler and no stranger to waking up under a pool table—just the type of man they were looking for. When Hellman asked if he wanted to become his protégé—and eventually open a school—Holland turned in his prison badge the next day.

The showstopper involved a Louisville Slugger. Four to six men would hold a wooden baseball bat steady so that Schulmann could split it in half with his shin. Even in success, the trick was excruciating.

Along the East Coast, martial-arts schools competed for students—and spewed venom, each insisting their form of judo, karate, or tae kwon do was superior. “Everybody hated each other,” says Mark Glazier, who owned karate schools in New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania. “It was like the old days in Japan.” Early on, Schulmann and Mehrkar stormed into a rival dojo that was shit-talking them, stepped onto the mat during a class—a massive fuck-you to the sensei—and made an ultimatum: “Put up your hands or shut up.” The sensei was humiliated. He soon closed down.

Karate schools are a straightforward business. Pack the mats with students, as many times a day as you can, and keep people coming back for higher color belts. Kids are typically about 80 percent of your customers, and profit margins are high. A successful dojo in the suburbs should have 250 students, and in the city perhaps a hundred more.

But most black belts make terrible small-businessmen. Schools limp along with fifty or a hundred students, barely enough keep the lights on. And in the 1980s, martial-arts marketing was abysmal: an advertisement in the Yellow Pages with an intimidating headshot of the owner and bullet points of the obscure disciplines he’d mastered.

Schulmann, though, was a natural marketer with a flair for the dramatic. He held live demonstrations at high schools, strip-mall parking lots, and theaters before screenings of movies like Blood Sport and Sidekicks. Students spin-kicked cigarettes out of Mehrkar’s mouth and broke boards and blocks. A lot could go wrong. Hellman, a top sensei, once attempted a spinning round kick at a block of ice and instead sliced off a chunk of his heel. It was a punishing way to sell a handful of two-for-one class specials for $9.50, but it worked.

The showstopper involved a Louisville Slugger. Four to six men would hold a wooden baseball bat steady so that Schulmann could split it in half with his shin. Even in success, the trick was excruciating: busted blood vessels, a massive bruise, and permanent calcium deposits after healing.

Schulmann’s acolytes enthusiastically followed his example—sometimes to painful extremes. At the opening of his own dojo, Steve Curran, an ambitious sensei, tried to break two bats at once. Instead, his shin snapped so badly that his foot could touch his knee. He left in an ambulance.

As the business grew, Schulmann decided that he needed a new name. United American Karate was difficult to trademark. He market-tested “Tiger Schulmann’s Karate.” One respondent said it sounded like an aggressive accountant. But the name stuck.

Steven Holland breaking a Louisville Slugger on the Seaside Heights, New Jersey, boardwalk circa 1992.

Growing a chain of karate schools is all about maintaining a culture of discipline and excellence. Creating one successful dojo is doable. Building a brand? It requires people you trust. Ron Schulmann, Danny’s athletic and soft-spoken younger brother, enlisted to help him expand the empire.

The Schulmann brothers and Mehrkar visited their black-belt students’ homes and met with parents—who were grateful that their wayward sons had finally found a purpose. Tiger’s team brought copies of monthly profit statements, sometimes upwards of $15,000 per school.

Then they made the pitch. Open your own dojo, an investment that could cost as much as $165,000. Franchisees would later describe the terms as outrageous: Pay a 10 percent management fee off the top and then own just 49 percent of the school. These unlicensed franchises were then required to buy gloves, gis, and other apparel at huge markups from Schulmann’s apparel company, later named Tigear. The owner-instructor, meanwhile, got a base salary of just $250 a week. When one young black belt asked to consult an attorney, Schulmann “belittled and reprimanded” him, according to subsequent litigation, and said he “had no right to question his mentor and superior.”

And still, they signed on. “Think about it,” Mehrkar tells me. “They come in because they don’t have self-esteem. You’re a nobody outside the school. But when you’re inside, your belt means something. And they were getting a lot of girls, and they were getting a lot of parents.”

Indeed, fraternizing with moms—some single, many married—was a major perk. The sensei had given her kid confidence, maybe even taught a Mother’s Day class. Her husband wasn’t the man she’d married, and now the sensei was looking at her like a woman for the first time in years. “You know what a badge bunny is?” asks Holland, who owned the Toms River, New Jersey, dojo, referring to women who romantically pursue police officers. “We had belt bunnies.”

They came into Holland’s office and locked the door or found him at bars and slipped their hands down his pants. One woman, he says, came to his dojo every morning in nothing but garters and a trench coat. Encounters with the senseis during class weren’t uncommon either. “Kids are out on the mat,” says Rob Shirey, who skipped joining the Army to open a school in Philadelphia. “And they’re banging them in their office.”

Schulmann’s rivals ran their dojos like regular businesses—a huge mistake, he says. In the martial-arts world, money flows from power, not the other way around. “When it gets down to it, it’s ‘Can you kick my butt or not?’ ” says Steve Bosyk, the franchise’s longtime chief operations officer. And no one could intimidate like Schulmann. The power translated into profits: By 1991, Schulmann was paying himself more than $100,000 a month.

The opening of the Toms River dojo in 1990, complete with Power Ranger.

The aggression carried over into competitions. When his fighters were down a few points, Schulmann directed them to make illegal hits. “So you would go in there and do a jump spinning back kick and knock him out of the fucking ring, cave in his chest,” Holland says. The referee would deduct a few points for the violation. “But guess what? That guy didn’t come at me again. And now I could win.”

At Sony Plaza on Madison Avenue in New York, Holland and his top students broke blocks and performed katas before an official screening of The Next Karate Kid. One pupil had recently been hit by a car and couldn’t attend. Hilary Swank autographed a glossy for him, but Pat Morita refused. Holland went apeshit, and Morita relented. Even Mr. Miyagi wasn’t safe.

Sticking it to bullies was Schulmann’s real passion. Once, when he visited Mark Glazier’s dojo in northern New Jersey, he saw a sensei abusing several white belts, the lowest level. He grabbed a gi from Glazier’s office and went out onto the mat. “When it came to me, I put a beating on him,” Schulmann says with a smile. Glazier drove his sensei to the emergency room with cartilage sticking out of his nose. But Schulmann knew that if you protect a man, he’ll be safe for a day. Teach a man to punch and kick, and he’ll be safe for a lifetime. That was the mission.

For some senseis, the trade-off of Tiger’s martial culture—sex, power, and fraternity in exchange for low pay and draconian rules—was too much. “I began to feel that I was a servant or slave of Schulmann,” wrote an early owner-instructor, Shimon Ben-Mashiah, in subsequent litigation. “Although respect is an important element of karate, slavery or involuntary servitude is not an element of martial arts, and is against the law and public policy.”

Ben-Mashiah told Schulmann that he wanted out of his Long Island dojo so that he could join his uncle in the diamond business. Schulmann agreed. But Ben-Mashiah didn’t leave the karate world as he’d promised. Instead, according to court filings, he took his school’s enrollment list, reassigned himself the valuable 731-KICK phone number, and secretly opened two new schools.

This betrayal could not stand. “They do things, and they think there’s no consequences,” Bosyk says. “They’re like, ‘I’m gonna do this. I’m gonna betray you. I’m gonna lie to you . . .’ ”

Ron Schulmann finishes his thought: “And I’m gonna hide behind the law.”

Schulmann watching fighters spar at the Tiger Schulmann’s Martial Arts facility in Elmwood Park, New Jersey.

On the night of August 12, 1991, Shahrokh Mehrkar walked into United Fitness Center carrying a subpoena. “Shimon Ben-Mashiah!” Mehrkar shouted. “You’ve been served!” Ben-Mashiah fled into his office, and Mehrkar tore at the door handle while children as young as seven looked on in horror. Schulmann was waiting in the parking lot, and the two of them sped away.

The lawsuit alleged that Ben-Mashiah’s new dojos violated his noncompete clause. Schulmann couldn’t resist further humiliating him in court documents. “If Shimon, a Saiko Shihan, truly believed these men were dangerous, he would not have cowered in his office and left . . . a brown belt woman and several children alone to defend him.”

Ben-Mashiah soon got a temporary order of protection. He was right to be afraid. Schulmann’s senseis were furious. “He hit Tiger,” says Nick Gravina, a loyal foot soldier who opened his first dojo with Schulmann at just nineteen years old. “He hit all of us.”

One Saturday night, Gravina and his brother Vince drove to Ben-Mashiah’s Levittown school. They expected it to be empty, but when they peered through the window, they saw Ben-Mashiah training with a group of instructors, who soon surrounded them in the parking lot. The Gravina brothers went back-to-back and took on half a dozen senseis. “We smashed ’em,” Gravina tells me. He tried to eye-gouge Shimon’s brother, Chagai Ben-Mashiah, and thirty years later his palm is still scarred where Chagai bit him. Such was the animosity that after the cops cuffed them all face down in the parking lot, Gravina slurped up oily water from a puddle and spit on Shimon.

Students watched in horror as Ron Schulmann and the Gravina brothers burst into the dojo wearing black gis. “I'm going to fuck you in the ass and break every bone in your body!” shouted Vince Gravina.

Tiger Schulmann got into the action too. He recruited two lieutenants, stormed into Ben-Mashiah’s dojo, and as twenty kids watched from the mat, Schulmann closed the office door and went to work. He choked Ben-Mashiah; threw punches, headbutts, a right hook, and then a left. He broke Ben-Mashiah’s nose and left him with a sprained neck.

KARATE EXPERT IS HIT WITH ASSAULT CHARGE, read the headline in Newsday’s coverage of the turf war. Schulmann, thirty-one, “exhibited tremendous restraint” in the altercation, his attorney told the paper. “The loser starts it and the winner gets prosecuted, and it was never more true than in this case.”

It was another marketing coup. Tiger Schulmann was selling self-defense, and the beating coverage was earned media. On the radio, Howard Stern and Robin Quivers joked that they’d rather learn karate from Schulmann than the guy left with a fractured nose. “It was the best advertisement,” Bosyk says. “The phones were lighting up.”

Schulmann was eventually acquitted. He boasted to Mehrkar that he’d followed his father’s advice: If you fight someone, do it alone so that it’s his word against yours.

Schulmann pursued Ben-Mashiah through the courts for years, even serving Ben-Mashiah’s students—some as young as eight—with subpoenas for depositions. The litigation “borders on a personal vendetta, as Schulmann knows I have no assets and have filed for bankruptcy,” Ben-Mashiah wrote in court filings. Schulmann eventually won a six-figure judgment. Schulmann later heard that Ben-Mashiah killed himself, a detail he relates with a shrug.

Schulmann getting in the octagon to demonstrate correct striking form.

By now, profitable “McDojos”—martial-arts franchises with dubious techniques that purists dubbed “bullshido”—were proliferating, and outsiders wanted a taste. In the mid-1990s, an ambitious young stockbroker named Jordan Belfort, whose story would later be chronicled in the movie The Wolf of Wall Street, offered to take Schulmann public.

But Schulmann was all about slow growth. He opened schools not when he found a ripe location but when one of his black belts was ready to take over. He also had a nose for scoundrels, and he smelled one. He declined. His friend Mark Glazier accepted Belfort’s offer, and his four-location franchise went public with the ticker symbol KICK. Belfort soon agreed to leave the securities industry. Master Glazier Karate International foundered, and Schulmann scooped up his schools on the cheap.

By the mid-1990s, Schulmann’s karate empire sprawled across four states. Keeping senseis motivated and fit—and kicking up cash—required a firm hand. Every Tuesday, owners arrived at corporate headquarters in Paramus, New Jersey, for an intense morning of sparring, followed by a business meeting.

Mehrkar looked forward to these weekly sessions, which he called the “Tuesday beating.” During sparring sessions, someone would call “Switch!” and senseis who weren’t enrolling enough kids would find themselves facing him. “I would give them a little bit of an attitude adjustment,” Mehrkar says with a laugh. “It always worked! Then all of a sudden the numbers would come up. Because they get lazy.”

Once, Mehrkar knee-kicked a sensei in the face. “Wow,” he said. “Your nose is on your cheek.” Instructors held down the screaming instructor while Mehrkar reset his nose. Schulmann wielded a wooden sword called a shinai. Arrive late or forget to keep your hands up and you got welts that could last for days. Senseis dubbed the bruises they sustained while sparring “Kyokushin tattoos.” Instructors limped from the dojo with cracked ribs and torn ACLs.

“[It got] to the point where you questioned if you should step out of line again,” says Rob Shirey, the Philadelphia school owner. “You’re dreading going up the following week because you’re still in pain from the previous week.” The physical fear was matched by a financial anxiety: Because of the draconian contracts they’d signed, they could only sell their stakes for pennies on the dollar. “You’re not going to get your money back,” Mehrkar told the senseis. “If you want to leave, leave.”

(Schulmann acknowledges “motivating” students with a shinai, which was common in karate schools at the time. He adamantly denies punishing underperforming owners, though he can’t speak to Mehrkar’s behavior. “It’s a made-up story to make me look like a tyrant,” Schulmann says. With regard to buyout prices, Ron Schulmann explains that because classes were prepaid, buying into a school was actually a liability, because the new owner was agreeing to teach thousands of free classes.)

A man once came into the dojo with tears in his eyes, begging an instructor to stop sleeping with his wife. "It was the Flint, Michigan, of toxic masculinity," says one former aspiring sensei.

Industry sources estimated that Tiger Schulmann’s Karate was now grossing $15 million a year. Schulmann bought a house in Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, and installed a home gym, a steam room, and sparring mats. Mehrkar was making a small fortune too: His protégés were required to kick up a percentage of their earnings, netting him tens of thousands a month.

But in other ways, the two men were headed in opposite directions. Mehrkar spent freely and dabbled in get-rich-quick schemes and Scientology. When Steve Bosyk, the COO, bought a Lexus, Mehrkar mocked him by dropping brochures from Lamborghini and Ferrari dealerships on his desk: “What, are you only gonna drive a Lexus all your life?” And he reveled in his power, threatening people at the gym, on vacation, even at home. When a judge asked him about his wife’s credible claims that she’d been subjected to hours-long beatings, he denied it but added sarcastically, “To be honest, what I do for my job, I don’t need two hours to beat her up.”

Schulmann’s sculpted body and fearsome reputation landed him on the cover of Black Belt magazine, but he was a softy at home. He started training his two daughters early on. He’d sneak up during Saturday-morning cartoons, put them in a light choke hold, and ask, “How do you get out of this?” He burst into tears when they gave him Father’s Day cards. In the mid-1990s, a young cousin, Nissim Levy, was getting into street fights. His family begged Schulmann for help, and Levy came to live with him. “Imagine going from Far Rockaway to Upper Saddle River,” Levy tells me, still oozing gratitude. He began training with Danny and Ron, worked at the Chelsea school, and later became a franchisee himself. Family was everything in Schulmann’s world.

Schulmann loyalists say he and Mehrkar were total opposites. Schulmann was Mufasa to Mehrkar’s Scar, light to his shadow. They squabbled over money. Mehrkar, meanwhile, began whispering to senseis that Schulmann was cheating them. Among the disgruntled was Steven Holland. When he left, Schulmann refused to buy out his share of the Toms River school he’d built into a local powerhouse, a stake he felt was worth roughly $70,000.

But Holland wasn’t just another nobody. His dad was a somebody: a state senator. In November 1995, the New York attorney general’s office contacted Schulmann, all but accusing him of committing franchise fraud. Schulmann ignored the first letter, then the second. Prosecutors began calling in senseis for interviews. Most didn’t flip, but a few did.

“Turn off your recorder,” Mehrkar told the prosecutor. “You’re going about this all wrong.” He then proceeded to make the government’s case for them—and set off a war.

Pat Morita and Hilary Swank, in front, at the premiere of The Next Karate Kid in Manhattan in 1994. Ron Schulmann is standing behind Morita, and Shahrokh Mehrkar is behind Swank.

On the night of July 21, 1997, Ron Schulmann and the Gravina brothers arrived at the Hub, a strip mall in West Nyack, New York. Nestled among a pharmacy, a bank, and a grocery store was Thomas Clifford’s Karate Academy. Their target: a turncoat named Patrick DaCosta.

A year earlier, amid the attorney general’s investigation, DaCosta and three other senseis had failed to show up for a Tuesday meeting. A few hours later, Mike Sachs, the chief financial officer, dropped a two-inch-thick lawsuit on Schulmann’s desk. Boom. They were suing the company for fraud and breach of contract. DaCosta had good reason to be upset. The Schulmann brothers had all but promised DaCosta a six-figure income if he agreed to pay $165,000 to take over the Spring Valley school. He’d even put up his family’s property as collateral. In the end, DaCosta never made more than $35,000 a year.

Since leaving, things had been looking up for DaCosta at his new job. Just weeks earlier, the local newspaper profiled him as a beloved local role model. “Adults and children say a class taught by DaCosta is something special,” wrote the Journal News.

Now those same students watched in horror as Ron Schulmann and the Gravina brothers burst into the dojo wearing black gis. “I’m going to fuck you in the ass and break every bone in your body!” shouted Vince Gravina. He elbowed the school owner, Thomas Clifford, and then Ron Schulmann issued a warning to DaCosta. “This is not over,” he said. “I’ll take care of you. I’m going to kill you.”

When Clarkstown police arrived, Clifford was shaken. Tiger Schulmann, he told officers, was afraid of his expanding karate chain. He worried the “turf war” could escalate. The Schulmann brothers were “a throwback to feudal Japan,” DaCosta told The Wall Street Journal.

Schulmann had been deeply stung by their betrayal. “When you do great things for people, you don’t expect they’re gonna turn on you,” Schulmann says. Now these traitors would feel his pain. Shirey, another sensei-turned-plaintiff, arrived at the Orange County courthouse for a hearing, but Schulmann was a no-show. As Shirey exited the courthouse, fifteen black belts surrounded him and his wife, and Ron Schulmann punched him in the head. (Ron was convicted of second-degree harassment and paid a hundred-dollar fine.) Someone also kicked down the front door of the home where he lived with his wife and young daughter. “It was just a nightmare,” Shirey says.

Schulmann’s karate empire was under siege. In New York, a state judge now barred him from opening new schools and ordered him to stop his “heavy handed” intimidation tactics. In December 1996, the Pennsylvania attorney general sued too, accusing the karate chain of violating the commonwealth’s Health Club Act.

Even parents were upset. Mehrkar had developed an aggressive upsell strategy in which, after her son took a few dozen classes of a 150-session pack, the instructor encouraged Mom to buy an additional black-belt package of 350 classes. The New York attorney general dubbed the sales technique a “bait and switch.” Parents staged protests outside schools and claimed they were being stiffed on refunds. “Basically, it’s the feeling of a cult,” one parent told The Philadelphia Inquirer. “Schulmann looks at you and says, ‘Have I ever steered you wrong?’”

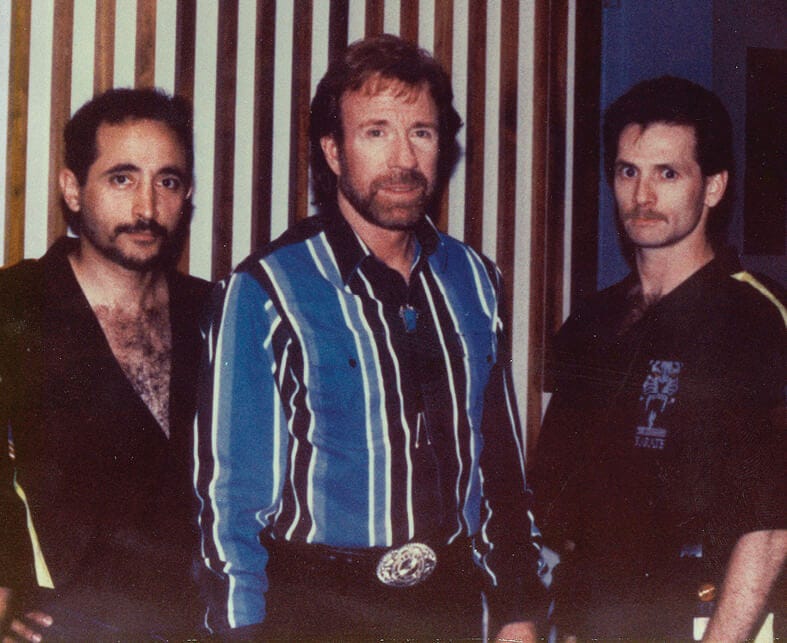

Chuck Norris flanked by Mehrkar (left) and another Tiger Schulmann sensei in 1993.

And yet still they came. The product on offer—join a martial brotherhood where you lost weight, kicked ass, and maybe got laid—was too good. To this day, even Schulmann’s most vicious critics have total admiration for the training program he developed.

In 1997, Elliot Spiegel was volunteering at the Fourth of July parade in Paramus when he saw a contingent from the local Tiger Schulmann dojo. Spiegel was a heavy guy at five-foot-eight and 330 pounds. But the idea of getting stronger intrigued him. At his free-trial class, he met sensei Vince Gravina, who struck him as “an uber alpha male,” he says. “The mold was made from that guy. Apex predator number one.” He thought, I want to be like that.

Spiegel started training two days a week, then five, then weekends too. Was he committed? “Oh yeah,” says his wife, Fran Spiegel, with a laugh. “He was all in.” At home, he shouted at his four-year-old son: “Make a choice! Be the hammer or be the nail!”

Spiegel earned a black belt, quit his sales job, and began working under his sensei for $25,000 a year. He wasn’t anyone’s image of a karate guy. He was so big that he couldn’t fit into even an extra-large karate outfit; instead, he wore white sweatpants around the dojo. But Spiegel knew how to sell, and it set him apart. Gravina, he says, wanted to keep “a smart Jew” like him around.

Spiegel was dedicated. Schulmann’s top senseis had it all: luxury cars, adoring students, and, for some, “body counts” off the charts. A man once came into the dojo with tears in his eyes, begging an instructor to stop sleeping with his ex-wife. “It was the Flint, Michigan, of toxic masculinity,” Spiegel says today. Still, he dreamed of opening his own school. But while he’d gotten strong enough to break cement blocks, he hadn’t lost much weight. Schulmann wouldn’t let him attend trade shows, Spiegel says, because he was embarrassed by his size. Spiegel finally tried a Schulmann-endorsed nutraceutical plan and lost fifty pounds. He was elated. He agreed to be photographed shirtless for a before-and-after ad campaign.

Schulmann watching fighters in the octagon.

In December 2001, Spiegel arrived at the big Challenge of Champions tournament. He stopped dead in his tracks. There was his meaty torso on a massive poster all right—but he was just the before photo. “I’m the fat skin that the ripped guy is walking out of,” he says. All around him, hundreds of kids carried postcard-sized versions of the ad. Other instructors howled with laughter. Spiegel was humiliated. Schulmann soon had him fired for insubordination, but Spiegel knew the truth. “I was a fat guy able to sell his program,” he says. “It made him crazy.” Schulmann initially denied the allegations, but today he’s unapologetic: “He’s selling fitness, he’s selling discipline, and he’s 350 pounds. It doesn’t make any sense.”

Spiegel was heartbroken. “I mourned,” he says. “My whole life was in and around karate for years. It was like putting me on a horse with one bladder of water and sending me into the desert kinda thing.” And he was angry. “I wanted his heart on a platter,” he says. Spiegel sued. The New York tabloids feasted, with headlines like TOO TAE KWON DOUGHY? and CHOP SUING: KARATE KING IN ‘FAT’ SPAT.

As the litigation dragged on, Spiegel’s sensei called. “I’m scared for you, Elliot,” he said. Spiegel felt it was a threat from Schulmann. “Sensei, you know who I know,” Spiegel replied. “He has kids. There’s nothing scarier than someone who’s got nothing left to lose. So tell him to be mindful of what he says and who he sends next.” (Spiegel tells me he was referring to a friend named “Mel,” his ex-girlfriend’s tough uncle.) Schulmann denies making any threats and then laughs. “I mean, yeah, he really knows some Jewish gangsters from New York,” he says. “Ridiculous stuff.”

But when you’re Tiger Schulmann and you have a winner’s attitude—and an attorney with a stuffed piranha in his office—good things can happen. A judge threw out Spiegel’s case. Schulmann settled Shirey’s lawsuit for a nuisance fee. He paid a $185,000 settlement to New York State, plus $36,000 in refunds to unhappy students. (“The state can beat anyone,” Schulmann tells me of the settlement. “The state is a Mafia.”) He beat the Pennsylvania attorney general on appeal. And after he buried Mehrkar under a mountain of expensive litigation, his partner-turned-archrival signed a legal truce.

Schulmann officially registered the business as a franchise, took a 16.5 percent fee, and put the past behind him. As the clouds parted, he was already deep into his newest project.

On November 12, 1993, cheesy graphics and synth music introduced the first ever Ultimate Fighting Championship. The format was revolutionary: all styles welcome, no holds barred, with bans only on eye-gouging and biting. In the debut match, Gerard Gordeau, a 215-pound kickboxer, faced off against Teila Tuli, a 410-pound sumo wrestler. Gordeau quickly landed “the kick heard round the world,” knocking out three of Tuli’s teeth, and a billion-dollar industry was born.

For martial artists, the UFC was a painful reality check that their personal style—which they’d studied for years and stormed into rival dojos to defend—might not actually be the best. For karate die-hards, the moment of truth came at UFC 2, in March 1994, when they watched Fred Ettish, a fifth-degree black belt, emerge from the tunnel in his gi. “I have absolute faith in my system of kenpo,” he announced before the fight. Kickboxer Johnny Rhodes proceeded to knock out Ettish’s mouthpiece, flatten him on his back, and stalk him around the octagon as he sprayed blood on the canvas, before finally choking him out.

“What is our purpose?” Schulmann asked his brother as the martial-arts world took stock. It was, they knew, to help kids defend themselves in street fights. They needed to innovate. The Schulmann brothers traveled to Las Vegas to train with John Lewis, a legendary jujitsu black belt, and slowly evolved their karate curriculum into a mixed-martial-arts hybrid of kickboxing (on your feet) and grappling (on the ground).

Schulmann soon created a fight team and packed arenas with hundreds of students, families, and fans, who intimidated opponents by chanting in unison: “TSK! TSK!” And he was just as combative as ever. In 2002, at the Grapplers Quest tournament in Bayonne, New Jersey, a judge disqualified one of Schulmann’s fighters for an infraction. After a heated argument, he shouted, “We are done!” TSK students refused to fight, Schulmann berated the promoter into issuing refunds on the spot, and they all filed out, never to return.

As the UFC produced a stream of stomach-churning injuries—snapped forearms, exploding cauliflower ears, bones shooting from kneecaps—along with big pay-per-view revenue, a funny thing happened. The temperature cooled in martial arts. Because no doubt remained about the dominance of this hybrid style of striking and grappling, there was no need for puffery and posturing. The dojo wars were over.

Schulmann launched a full makeover of his business. He changed the franchise name to Tiger Schulmann’s Martial Arts. And he installed cameras to monitor bad behavior and joined SafeSport, a nonprofit that polices sexual abuse in amateur sports. Ron Schulmann fired senseis who were too flirtatious and instituted a new policy for dating adult students—you had to commit to six months minimum to show you were serious.

I chuckle about the horny old days to Jimmie Rivera, a Schulmann sensei and onetime UFC bantamweight who has competed in bare-knuckle fighting. “You’re laughing,” he says, sounding like he wants to reach through the phone and box my ears. “But I don’t think it’s funny.” The world has changed, and so has the franchise.

Today the average Tiger Schulmann school feels more like a luxury health club than the testosterone-fueled, shouting-and-bowing dojo of yesteryear. “We’re much better at it,” Schulmann says of his ability to spot troublemakers. “We wouldn’t have a Shahrokh [Mehrkar] now.”

Schulmann and his crew have softened a little in middle age. They massage tender knees and shoulders, worry about college tuition and elderly parents, and dote on their kids.

Even the haters have calmed down. After he was drop-kicked from the karate world, Spiegel became a yoga instructor and life coach. Whenever he thinks about appealing his weight-discrimination case against Schulmann, he hears his “yoga self” ask: “Is it worth carrying that anchor around?”

There are exceptions. Mehrkar struggled to forgive and forget, he says, as he watched Schulmann grow his empire with impunity. Mehrkar himself felt swindled out of millions. He was furious—and tempted to do something about it. He knew Schulmann’s daily schedule and home address. “One of the reasons I moved to Vietnam is because I was afraid that I might do something,” he tells me. “Get a gun and shoot Schulmann.”

I relay this threat to Schulmann in Sarasota, Florida, during an interview across the bay from his luxury condo, as he’s halfway through a Ritz-Carlton cheeseburger. He laughs. “I learned this in life,” he says. “Someone who’s really going to do something, he doesn’t say anything.”

Schulmann is held aloft by fighters at his gym in Elmwood Park, New Jersey. His brother Ron Schulmann is pictured at far left.

Don't be fooled by the powerful shoulders and the unlined face. “I’ve been on the earth for a very long time now,” Schulmann says. At sixty-two, he knows age isn’t just a number. “It’s old, believe me. It’s old.” Like his senior lieutenants, Schulmann insists he’s mellowed out too. He watched his daughter Danielle date a series of not-so-good guys. But he restrained himself, said nothing, let her make her own decisions. He cried during the vows at her beach wedding when she finally married Mr. Right. Schulmann has arthritis and sciatica, but that night he danced the hora with abandon.

And yet.

And yet, there is a saying about a tiger and his stripes.

And yet, on the night of January 1, 2021, Schulmann was in Key West with his second wife, Kim; two daughters; sister Ruth; and others. They ate dinner on Duval Street, a lively stretch of bars and restaurants. At 10:30 P.M., mounted police began enforcing a curfew. They had bullhorns. They were aggressive.

It had been a difficult year for the Schulmann family. David, the patriarch, started 2020 in a nursing home. Danny and Ron visited him daily. When Covid hit that spring, he contracted the virus and went on a ventilator. David Schulmann had survived the Gestapo in Berlin and the Japanese imperial army in Shanghai, slept between jobs in Central Park, and fended off armed robbers in small-town Pennsylvania. But he died alone in a hospital bed, saying goodbye to his four children on a telephone held by a faceless nurse covered in PPE.

And then, walking on the sidewalk, pandemic curfew in force, Schulmann says police officers began pushing his daughters. He told Arielle, his youngest, to start filming. An officer grabbed her arms and threw her to the ground. Schulmann snapped. He pushed a cop, and another tackled him onto the ground. Schulmann lay on his back in a classic jujitsu guard position, kicking and kneeing with fury as four cops dogpiled him.

In his mugshot, Schulmann stares off into space, already over it. His plea deal included an online anger-management course. “It was very good,” he says. “I’m not sorry I took it. It was very psychological, and it taught you some things.”

Does he remember any specific tools for controlling his temper?

“No,” Schulmann says. He smiles. His eyes dance with delight. “Nothing.”

Opening image: Schulmann photographed at the Tiger Schulmann’s Martial Arts gym in Elmwood Park, New Jersey.

David Gauvey Herbert writes about crime, subcultures, and general weirdness for New York Magazine, Bloomberg Businessweek, and The New Yorker. He is also a two-time grant winner from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. He lives in Brooklyn.

esquire