How a Brutal Beer War Led to the Downfall of the Brewery That Made Milwaukee Famous

The year is 1965. Thirty-four-year-old Bob Martin relaxes in his high-backed leather chair and exhales with satisfaction. His office, perched within the imposing headquarters of the Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company in downtown Milwaukee, hums with the quiet authority of power. As well it should for the guy who’s running the marketing department for “the Beer That Made Milwaukee Famous.” Schlitz is the second-largest beer empire in the world behind only Anheuser-Busch. And it is Martin’s playground, his kingdom to control.

A secretary’s voice crackles through the intercom. “Mr. Martin, there’s an unidentified caller on the line. Won’t give a name. Says it’s urgent.” Martin frowns as he picks up the phone. A voice on the other end—flat, emotionless—says, “The baby has arrived and is doing nicely.”

Click. Silence. Martin stares at the receiver. Was the call a threat? A prank? No, it was a message. The cryptic call confirmed that a payment of $225,000—the equivalent of $2.3 million today—had been received. And what was that money for? To finish building the Houston Astrodome, the first domed stadium in the world. If all goes according to plan, Martin knows, Schlitz will soon have the exclusive rights to the beer taps inside the stadium.

It wouldn’t be the last time Martin used a fat stack of cash to cut a deal. The Astrodome arrangement typified Martin’s interpretation of marketing—he was the guy who made things happen. Since the age of twenty-five, Martin had not only been running Schlitz’s marketing but also shaping its empire. And he answered to only one man: Robert Uihlein Jr., the heir to the Schlitz dynasty.

In the brutal beer wars of the sixties and seventies, Martin was a general. His influence extended far beyond ad campaigns and sales strategies. He was the power behind the power, the guy who knew how to get things done—legally or in other ways.

But this is much more than a story about a marketing guy on the edge. It’s the tale of how a billion-dollar empire imploded. Because Schlitz wasn’t just a beer manufacturer; it was a ticking time bomb of illegal activity. The company would eventually find itself at the heart of a 747-count indictment by the Securities and Exchange Commission. It would alienate its customers with sludgy beer and in-your-face TV advertising gone wrong. And it would start to fully unravel with a young prosecutor simply opening a desk drawer.

Beer Capital of the WorldMilwaukee in the 1960s was a lot like Silicon Valley in the 2000s—the center of the action. Everyone wanted to work in beer. The industry was stylish and sexy. And perhaps the only thing that flowed more freely and frequently than the brew itself was the cash. How did Milwaukee earn its title of Beer Capital of the World? Thank immigrants, specifically Germans. Between 1820 and 1900, nearly five million Germans immigrated to the U.S., and where go Germans, beer often follows.

Now, if you’re the typical beer drinker under the age of fifty, you might only know Schlitz as a brand with the sheen of nostalgia that’ll set you back seven dollars a can at your local hipster watering hole—an ironic middle finger to all the microbrews currently flooding the market. But when Martin came rolling into 1950s Milwaukee—a segregated and very working-class city in the heart of the rust belt—it was a place where if you put in a forty-hour workweek at a local bottling plant, you could raise a family and easily settle into a middle-class lifestyle.

The Schlitz Building at Schlitz Park in Milwaukee in 2018. It was once the headquarters of a billion-dollar beer empire.

Martin, like everyone else in Milwaukee, wanted to work at Schlitz. It was the second-best-selling beer in the U.S. behind Budweiser, its rival down in St. Louis. But Schlitz wasn’t the only brewery in town. Milwaukee was home to Pabst, Blatz, and Miller as well. And the big four powered the city like no other industry.

In fact, Milwaukee was such a scene that Hollywood took notice. In 1976, at the height of Schlitz’s popularity, ABC Television aired the first episode of Laverne & Shirley, in which stars Penny Marshall and Cindy Williams—sharing a cramped basement apartment in downtown Milwaukee—toiled in the bottling department of a Schlitz doppelgänger called “Shotz.” Fittingly, the sitcom ran until 1983, ending its run at right about the time Schlitz was decimated and sold off for parts to rival Stroh Brewery.

In a series of interviews several years ago at his home outside Kansas City, Martin, who died in 2023 at age ninety-three, reminisced about his days at Schlitz and recalled how he got his start at the company. Luck was on his side. Martin got on the radar of Paul Pohle, a Schlitz executive and former fraternity brother. Martin was hired right out of college in 1952 as a junior analyst in the market-research department. “I didn’t even know how to spell ‘market research,’ ” Martin admitted. “I had never even heard of it. I just wanted a sales job at Schlitz, but they wouldn’t put a guy under twenty-five in sales. They wanted someone with, as they put it, ‘established drinking habits’—which is hilarious.”

Thus, Martin took what he called a “crummy job” in market research at Schlitz for $300 a month. But timing worked in his favor. Just three years later, as Pohle climbed the corporate ladder, Schlitz executives needed a new head of the research department. None of the outside candidates impressed the muckety-mucks, so Martin got the promotion. “They didn’t give a shit who ran the research department,” he said in one of our interviews. “If it was [looked upon as] an important department, I wouldn’t have gotten it.”

That was just his first step up the ladder. Soon the ambitious Martin would be calling the shots on strategy and spearheading an escalation of the beer wars, with disastrous consequences.

Battling to Be No. 1The big domestic brewers were engaged in an all-out war for brand supremacy long before Martin entered the fray. It was a blood sport that didn’t flow red and viscous but rather golden and frothy. But no two beer makers had a more vitriolic rivalry than Budweiser and Schlitz. Schlitz had been the best-selling beer in the U.S. in the early 1900s and again when Prohibition ended in 1933—by 1940 it dominated the market. But by the 1950s, it found itself tussling over the top spot with Budweiser. And in 1957, Bud passed Schlitz as the number-one-selling beer and held on to the advantage.

By the mid-1970s, when Martin was at the height of his power, Schlitz was tired of coming in second. Martin and his fellow executives decided it was time to shake things up and make a big play to take down Budweiser.

But to really understand the background of the beer wars, you first need to know the rules—the beer rules. Here’s the short version: If you make booze, you can sell it only to wholesale distributors. (The movie Smokey and the Bandit is based on this rule. Well, that and car chases.)

In the 1920s, Prohibition had ushered in a three-tier system for the sale of beer made up of producers, distributors, and retailers (in that order). Martin, in an interview, described it this way: “You have to have a license to brew beer, you have to have a license to wholesale beer, and you have to have a license to retail beer. And in most places, it’s illegal to have a license for more than one.”

Why the complications? Money, of course. Each tier can be subject to a variety of federal, state, local, and other taxes, which means more and more beer money is siphoned into government coffers. There were also a multitude of middlemen between the breweries and their customers.

The scheme ran deep. Schlitz kept two sets of books to conceal illicit payments, spending millions annually.

The combination of that Byzantine regulatory environment with the ferocious competition for sales naturally catered to hard-charging execs who knew how to work the system. Martin prided himself on being able to do just that. And the Astrodome incident is a prime example.

Remember the mysterious phone call about the baby arriving safe? Well, the guy who delivered that line turned out to be legendary Houston businessman Roy Hofheinz, a former mayor of the city. He and Martin had a cozy relationship. Colloquially known as “the Judge,” Hofheinz was the artful, cigar-chomping Texan owner of Houston’s Colt .45 baseball team and the brains behind constructing the Astrodome. Imagine Hofheinz as a mash-up of Lyndon B. Johnson and George Steinbrenner.

Because Martin was responsible for baseball sponsorships at Schlitz in the sixties, he and Hofheinz became not just close business acquaintances but personal friends. So naturally, Schlitz decided it would sponsor the new Houston baseball team (which would later become the Astros), providing Hofheinz got the Astrodome built. In Martin’s unpublished autobiography, he recalls a time when Hofheinz was $225,000 short to finish the Astrodome.

Hofheinz’s creditors were asking for payment on a prior loan, thus preventing him from securing the additional funding needed to get the stadium built. Hofheinz was out of options to secure financing; his entire financial empire was on the brink of collapse. Hofheinz spoke in code, telling Martin what Martin already knew: Under Texas law, Hofheinz couldn’t borrow a dime from Schlitz, because the brewery sponsored the broadcasts of Astros games.

Martin, ever the problem solver, then recalled: “It occurred to me that $225,000 was a remarkably small sum considering his total debt . . . that $225,000 was really less than what we were paying every quarter to him for the broadcast rights.”

Here’s where Martin veers into a gray area of legality. Martin recalled telling Hofheinz, “There would absolutely be nothing wrong legally or otherwise for us to simply pay you early for the next quarter [of broadcast rights], which is coming up in a few weeks anyway. And this should solve your problem without causing any trouble for us or for you, legally.”

Would it? No matter. Hofheinz was in a bind and instantly accepted the offer—Schlitz’s “early payment” for broadcast rights secured the funding needed for the stadium. Martin just needed the official green light from Uihlein, who immediately gave it. More than a decade later, the Astrodome would appear among the catalog of charges against Schlitz.

Two Sets of BooksIf the Astrodome was a particularly dramatic instance of Schlitz’s prowess at under-the-table marketing, Martin and his compatriots had made it part of the company’s standard operating procedure by the mid-seventies. As federal prosecutors would later charge, Schlitz regularly paid inducements to secure dominance in “accounts of influence.” Think of it as payola for beer.

The Milwaukee Sentinel detailed how even minor transactions—like a Milwaukee sales manager funneling $1,208 for carpeting at Humpin’ Hannah’s Nightclub via an ad agency—were part of a broader money-laundering scheme. And who was at the center of this? Martin, of course. In one of our interviews, he recalled a cryptic call from a retailer warning him the FBI was coming for records linking Schlitz to bar refurbishments. Martin brushed it off. From his point of view, he was just doing business.

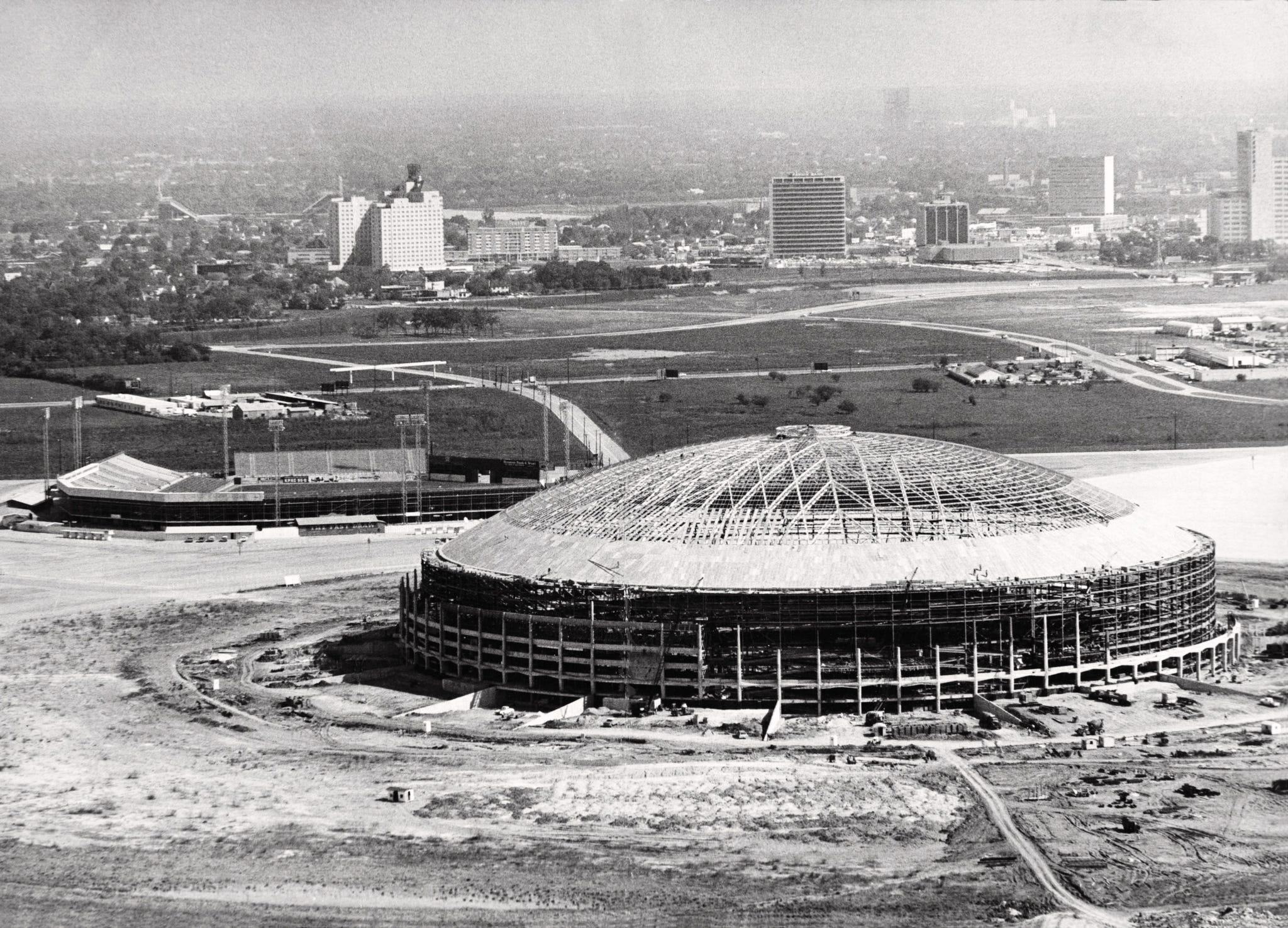

The Harris County Domed Stadium while under construction in 1964; it would later be known as the Houston Astrodome.

If Martin was the mastermind of the strategy, his top lieutenant in the effort was George Shay, a polished Amherst grad turned director of special accounts. The Securities and Exchange Commission indictment later pegged him as the key figure executing Schlitz’s aggressive marketing tactics. And a Washington Post piece made it plain: “Martin chose George Shay . . . to carry out the plan.”

From a distance, Shay was an unlikely candidate to fill that role. A world-traveling, blue-blood polyglot, Shay had majored in French; spent his summers in Grenoble, France; and spoke a bit of Turkish, Japanese, Malay, and Greek. But he was equally adept at managing Schlitz’s on-the-ground marketing. He was the guy making deals, securing placements, and ensuring bars were well stocked with Schlitz-branded gear.

The scheme ran deep. Schlitz allegedly kept two sets of books to conceal illicit payments. Testimony revealed that the company funneled $50,000 through an ad agency to the president of a restaurant chain called Emersons and secretly paid a Schlitz wholesaler to secure exclusive draft-beer rights from a Virginia seafood restaurant. Schlitz shelled out $75,000 to secure “sales priority” at Wrigley Field and had a similar deal with the Texas Rangers’ stadium. In total, the SEC’s indictment estimated that Schlitz spent $3 million annually—about $17 million in today’s money—on these tactics.

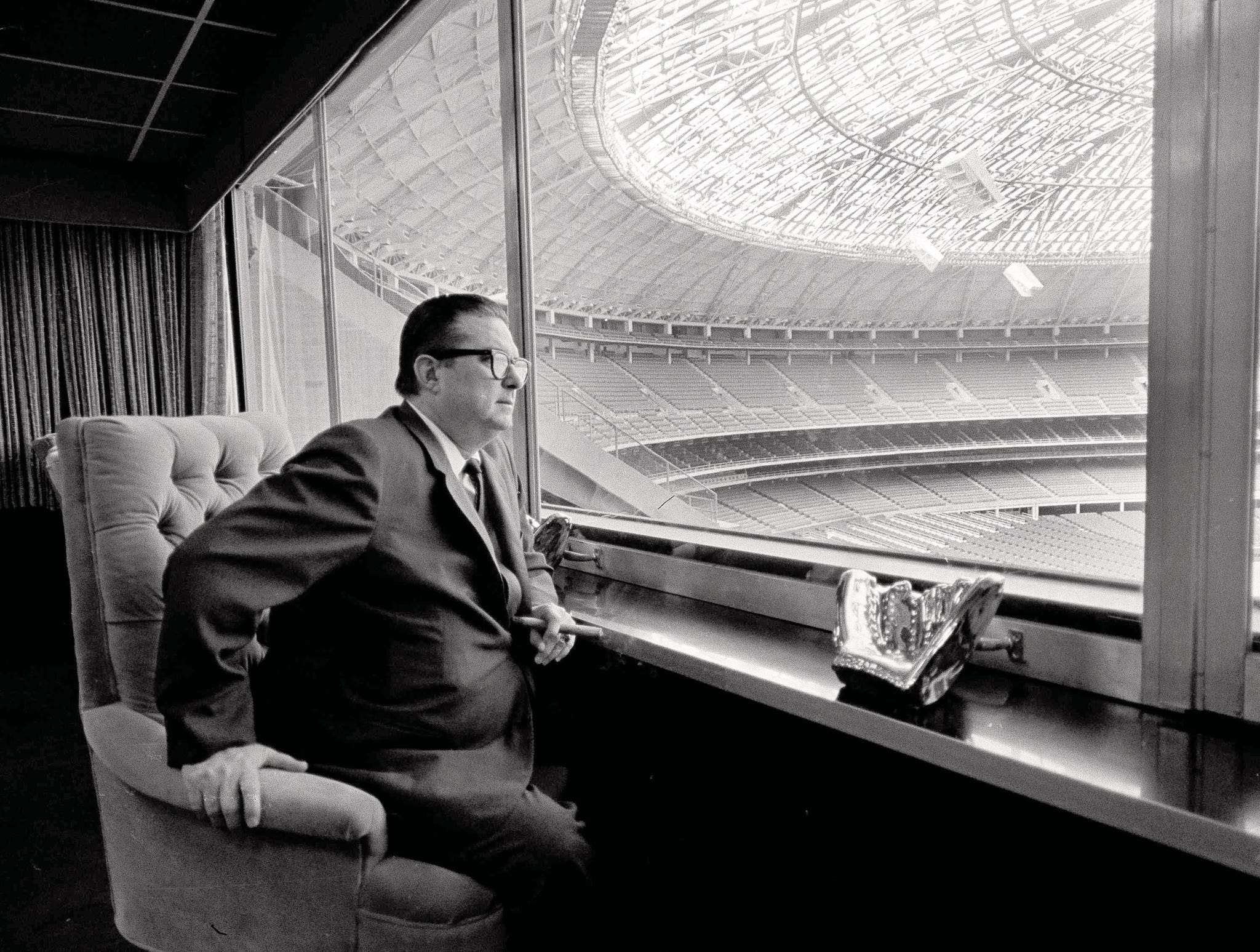

Roy Hofheinz (aka “the Judge”), the president of the group thatowned the Houston Astros, inspecting construction work being done on the Astrodome from aprivate apartment inside the stadium in March 1965.

One of the biggest plays? O’Hare Airport, the largest draft account in America at the time. Schlitz caught an incredible break. In 1976, a Budweiser strike left the airport dry, and Schlitz—just a quick hour’s drive north—seized the opening. Martin proudly recalled how they undercut Budweiser, using “marketing allowances” (read: questionable discounts) to lock in a deal. The SEC later accused Schlitz of making $265,000 in false-invoice cash payments to Carson, Pirie, Scott & Co., which ran O’Hare’s concessions. In Martin’s words, “We had to set up an arrangement where we gave [the wholesalers] a marketing allowance or some such thing. Things you make up so that you can give a discount, so that [the wholesaler] could handle it. But we got into O’Hare,” Martin said proudly, “and we had to make an adjustment to take care of it.”

Did Martin think anything was wrong with these maneuvers? In his autobiography, he dismissed the case as regulatory meddling, complaining that the ATF and state agencies were just catering to sore losers in the beer business. He mused, “the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (BATF) and state regulatory agencies . . . were particularly susceptible to the complaining and whining of those brewers who managed to be on the losing end of switches in the concession business.”

Opening Pandora’s DrawerIn the spring of 1975, Stephen Kravit was a third-year Harvard Law student looking for an opportunity in his hometown. Thanks to a connection from his insurance-salesman father, the bespectacled twenty-five-year-old managed to score a job interview with Bill Mulligan, a U.S. attorney in Milwaukee. Mulligan’s office appeared more like a hastily packed suitcase than the base for a powerful prosecutor. Feeling out of place in a government building with eighteen-foot ceilings and dwarfed by stacks of paper piled several feet high around him, Kravit recalls talking about himself for twenty minutes while the gruff, much older Mulligan sat silently behind his desk. Somehow, Kravit got the job.

A few months later, the newly hired Kravit again found himself in front of the imposing Mulligan in his disorganized office. His new boss pointed to a particularly sloppy, leaning tower of documents and, as Kravit recalled, “Mulligan says, ‘That’s the Schlitz case. We started an investigation a month or so ago. And we took a bunch of grand jury testimony on a statute that no one’s ever really looked at criminally before. We don’t have anybody that has any time for that. It’s yours.’ ”

Kravit didn’t have a proper office yet. So he moved the five-foot pile of files to his workspace in the office library.

Instead of golden ale, when drinkers popped open a chilled can of Schlitz, they got hit with a hazy, thick, sludgy foam.

If the U.S. attorney wasn’t yet taking the investigation into Schlitz too seriously, neither was the brewer. Schlitz was so confident that the U.S. attorney’s office would come up empty, in fact, that in 1976 its lawyers invited Kravit to their headquarters in downtown Milwaukee. What’s more, he was given free rein to rifle through any documents he could get his hands on. The lawyers reasoned that their two-year document-retention policy—directing executives to destroy anything more than two years old—would render whatever Kravit might find materially insignificant. That proved to be a costly miscalculation.

Kravit arrived at the offices early one morning, where he was cordially greeted by secretaries but not executives. He recalls, “Brand managers and the people who are responsible for national sales and things like that would come in around 10:30 or 11:00. And then they were all supposed to go out for lunch around town and buy beer for everybody. So they were never there for lunch.” He adds: “And I would say a very large number of them were alcoholics.”

Reminiscent of a scene out of Billions, the baby-faced Kravit began poking his head into empty offices and ended up in one belonging to Abe Gustin. Gustin’s title was director of national sales service, but in practice he was Martin’s lieutenant.

“I go into his office,” says Kravit, “I sit down at his desk, and there’s just some current paperwork about sales. I casually open a drawer because I can look anywhere, right? I open the bottom right-hand drawer and there is a pile of letters.”

Remember, this was the 1970s—if you wanted to keep a copy of your correspondence, you did so with green, pink, or yellow carbon-copy paper. “Gustin and a number of the other guys were vain,” says Kravit. “They wanted to keep their correspondence because they were proud of it.”

In essence, this was the moment that precipitated the downfall of a century-old global powerhouse. Inside the walnut-mahogany drawer—and in clear violation of Schlitz’s document-retention policy—Kravit discovered notes and letters going back to the 1960s, detailing key aspects of Schlitz’s bribery activities. All the proof lies in the notes, and the young lawyer knows he’s got them. “It’s very good proof of what exactly they were doing, because they weren’t hiding it,” says Kravit.

Despite this bombshell finding by Kravit, Martin, in our interview, responded to the 1970s investigations and accusations with a sigh and an eye roll.

“Kickbacks was a term that somebody threw in there,” said Martin. “What they were really concerned with . . . was questionable marketing practices, which were the responsibility of those people in the marketing department.” And who was the head of that department? Bob Martin.

Tasteless Ads, Tasteless BrewThe problems at Schlitz weren’t all legal. Beginning in the early seventies, the brewer made a series of spectacularly disastrous decisions in an attempt to gain market share. The first of these blunders affected the quality of the beer itself. Believing that the best way to outgun its rivals was to speed up production, the company devised something it coined internally as Accelerated Batch Fermentation (ABF), a process that shortened the brewing time to as little as fifteen days, versus thirty-two days for Bud. The results were akin to a bad chemistry experiment—drinkers, instead of seeing a frothy golden brew when they popped open a chilled can of Schlitz, got hit with a thick, sludgy foam.

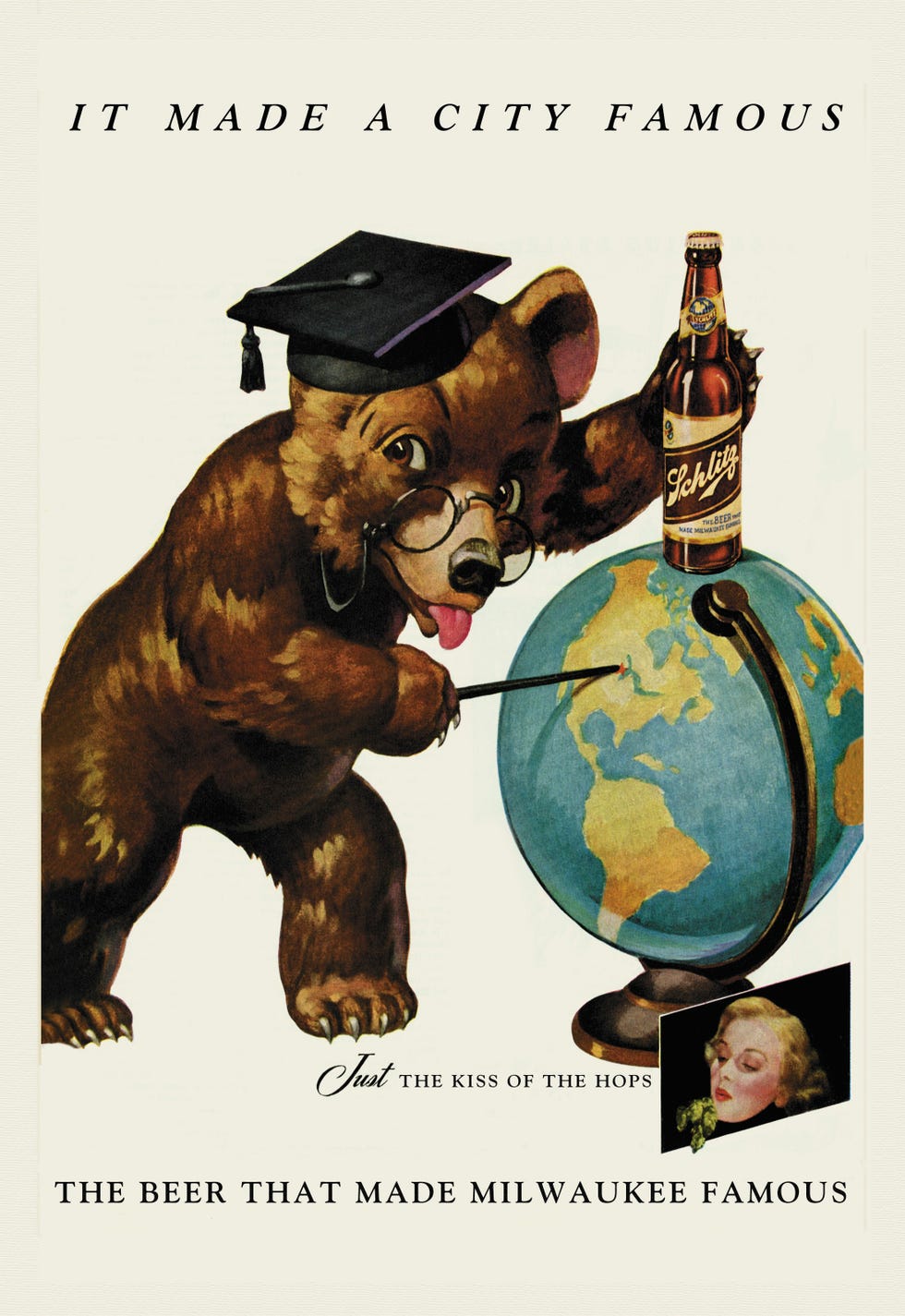

A print ad from 1942 leaned into the idea that Schlitz had put Milwaukee on the map.

Angry consumers rebelled, forcing Schlitz to secretly destroy ten million cans and bottles of beer and abandon ABF all together.

Skanky beer, however, was just one problem for the brewer. Schlitz was about to unleash what many industry experts consider to be one of the worst advertising campaigns in history. On paper, it shouldn’t have been. The brewer hired the Chicago advertising legend Leo Burnett—think of Burnett as a real-life Don Draper. But instead of clever spots that boosted beer sales, the ad campaign delivered Schlitz a devastating blow.

Derided by many at the time as the “Drink Schlitz or I’ll Kill You” campaign and playing off the hypermasculinity of the times, the television spots featured burly men and snarling boxers who threatened physical violence if someone were foolish enough to take away their cans of Schlitz. The reaction by the public was so negative that even today the TV spots are studied in college marketing classes as a warning on how not to market a product.

The double whammy of the off-putting ads and the sludgy beer alienated customers. Sales tanked from 24.2 million barrels in 1976 to 6.2 million in 1981.

Death of the ProtectorEven as Schlitz was hemorrhaging customers, the legal noose was tightening around the company. And after an exhaustive two-year investigation, Kravit and the feds dropped the hammer. On March 15, 1978, Schlitz was indicted by a grand jury on 747 counts alleging “illegal marketing practices”: three felony counts, one misdemeanor to violate the Federal Alcohol Administration Act (FAAA), and 743 misdemeanor counts based on transactions that allegedly violated the FAAA.

Though Schlitz wasn’t the only brewer who caught the eye of the SEC, it was the only company that had decided to go to war with the government. The rest of the breweries rapidly settled.

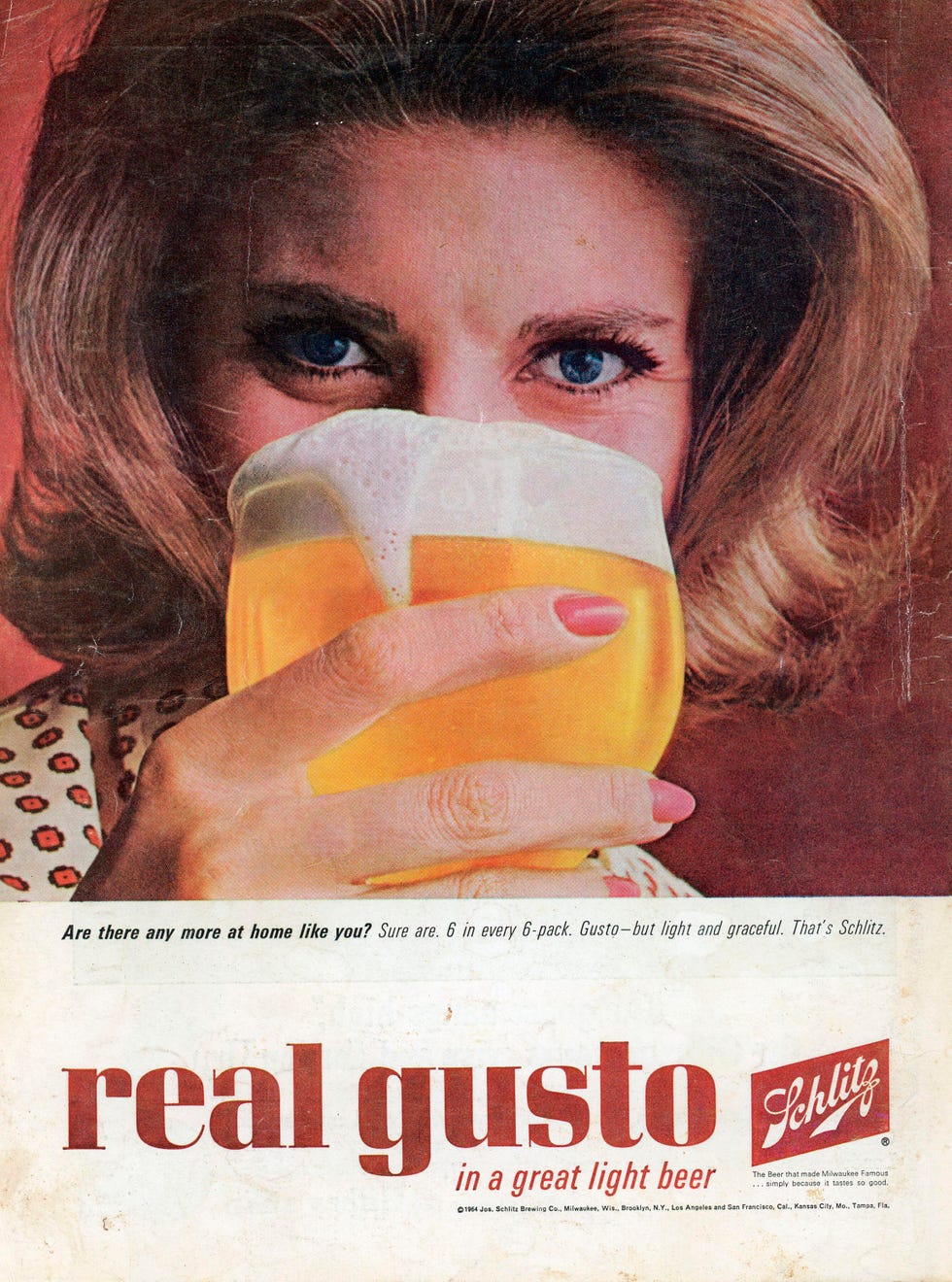

An ad in Playboy in 1965 brought a sexier, more playful attitude to the job of selling beer.

The accusations against the hundred-year-old brewer were vast and varied. They stretched from the sophisticated, like that payment to complete the Astrodome, to the more Dukes of Hazzard style, like paying off bootleggers in Alabama to run Schlitz into dry counties. When asked about the SEC indictments in our interview, Martin was dismissive: “It was a giant fishing expedition.”

Martin argued that it wasn’t the aforementioned abysmal decisions made by Schlitz nor the SEC indictments that caused the Schlitz implosion. Nope. According to Martin, what contributed to the demise of Schlitz “was Bob Uihlein making the mistake of dying.”

The Uihlein to whom he’s referring was one Robert A. Uihlein, the much-beloved, polo-playing company head and Martin’s number-one guardian. The Uihlein family had been running the brewery for a century—the family were the Milwaukee version of the Astors or the Morgans in New York City.

Martin recalled chatting with the elderly comptroller of the company, Werner Lutz. “Lutz always said, ‘If your name isn’t Uihlein, sonny, you’re hired help, and I’m hired help, too,’ ” Martin said with a laugh, mimicking Lutz’s German accent.

Even as Martin was running the beer war against Budweiser, his home life was unraveling. He’d met his wife, Diane Moreland, in college, and they had married soon after. But by the mid-seventies, their staid midwestern life was being upended by Diane’s struggle with bipolar disorder, which forced frequent hospitalizations and put a strain on the marriage. They separated and later divorced.

Right at about this time, Martin began a romance with Kaye Rusco—the sharp, politically savvy executive secretary to Uihlein. Before Schlitz, she had worked for the governor of Minnesota and had been one of the famed “Boiler Room Girls” on Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign. At Schlitz, Rusco was operating within the center of power, working directly for Uihlein and closely with Martin, whom she would eventually marry. As the SEC closed in, Rusco was “promoted” out of the executive suite—a move that appeared to be calculated to distance her from the scandal that was descending on Schlitz.

Uihlein had always had Martin’s back and given him full autonomy to run the marketing department the way Martin saw fit. It’s hard to believe that the duo weren’t in lockstep when it came to the extraordinary measures taken to increase market share. And it’s equally hard to speculate what Uihlein might have done to fend off the impending disaster. But Uihlein died after a brief bout with leukemia in 1976, and Martin no longer had his protector at the top of the company.

In fact, by the time the indictment hit, Martin was already out the door.

Holiday MassacreOn the morning of December 16, 1976, as the SEC investigation was beginning to accelerate, Martin arrived at his office as usual. But the mood was noticeably different. He was immediately summoned to the office of Schlitz’s newly installed president, Eugene Peters, who had taken over for the recently deceased Uihlein.

At his desk, Peters slid over to Martin a release and a waiver, followed by a check and a pen. Peters got right to the point: Due to the growing legal mess, he was firing Martin and explained that Martin was being terminated with cause. If he signed the release and wavier, said Peters, Martin could keep the check for $100,000 in severance.

In his autobiography, Martin recalls the moment and what he said to Peters, “ ‘Gee, in addition to the fact that this is certainly a lovely Christmas present that I much appreciate, I’m afraid I won’t be able to avail myself of the generous additional six months’ pay’—and proceeded to tear up the release and waiver and threw them into his wastebasket.” In that case, Peters said, they’d go to plan B, which allowed Martin not to sign anything and get $50,000, half of the minimum he was due for his twenty-five years with the company.

Schlitz didn’t just fire Martin, who at the time was still senior vice president of marketing. Peters also shitcanned Martin’s cohorts Thomas Roupas, the vice president of sales; Abe Gustin, the director of national sales services; and William Timpone, the director of field sales. The company reckoned they’d look better in the media tossing out a few corpses. As Martin recalled in his autobiography, “And that was kind of the end of my career at Schlitz.”

“What we want, Mr. Martin, is to put your ass in jail,” said the federal prosecutor, “which is certainly where it belongs.”

What Martin didn’t know was that Schlitz had already gone to the Milwaukee Journaland fed them the story of Martin’s firing, and it was picked up in multiple newspapers the following day. On the other hand, what Schlitz didn’t know was that amid the chaos of the SEC investigation, Martin had secretly received a stellar job offer: to be the president of United Vintners in California, a successful beverage-distribution company. But his new employer was a little gun-shy about taking on a company president being pursued by the government on massive counts of fraud.

Not long after Martin was fired, in early 1977, Kravit asked him—asked being the operative word here—to testify in front of a grand jury. Martin, seeing a potential way to clear his name and secure his new job with United Vintners, offered to make a deal. “I said, ‘I will come down and answer any question, truthfully, for one day on any subject that I know about,’ ” said Martin. “ ‘But at the end of that day, you have to give me a letter that says that you’re through with me.’ ” The letter would essentially be a get-out-of-jail-free card.

The government agreed to his request, and on a chilly morning in March 1977, Martin arrived at the federal courthouse in Milwaukee, an imposing Romanesque structure built in 1899.

Right off the bat, according to Martin, things didn’t go well. “I said, ‘Well, gentlemen, I’ve agreed to testify all day on anything you want. But maybe we can speed things along if you tell me what areas most interest you, or what is it that you want?’ ” Kravit’s reply was far less amicable.

Martin recalled that Kravit took his glasses off and said, “What we want, Mr. Martin, is to put your ass in jail, which is certainly where it belongs.”

Kravit doesn’t recall putting it quite that way, but after some jousting, Martin did eventually offer grand-jury testimony and Kravit got what he wanted. According to the Offer of Proof, written by Kravit laying out the scam, Martin testified, saying, “We knew this activity [payment of inducements] was in a gray area. It was standard procedure in the beer business to do it that way. And the BATF [Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms], which was a regulatory agency, had reviewed a number of things, to our certain knowledge, and nothing was happening to anybody.”

In a nutshell, Martin’s defense was: Everyone was doing it, and no one had been busted before. So why are you picking on me?

Out for VengeanceRather than just accepting the letter and taking a new gig at United Vintners, Martin now had another idea: revenge. And his vengeance would be cold and calculated. Schlitz had no idea what Martin was about to unleash on the company. The hubristic decision to leak the story of the Schlitz executive’s firing to the newspapers was about to be used against them.

As Martin recalled, “In the state of Wisconsin, you can get fired for any reason whatsoever. Except as long as it’s not exclusively malice. Well, how would you like to prove something’s exclusively malice?”

Though an employer couldn’t be sued for wrongfully terminating an employee, an employer couldbe sued for libel. And that’s just what Martin did. Once again, tucking himself nicely behind plausible deniability, in 1978, Martin filed suit against Schlitz and its then–chief executive Jack McKeithan, charging libel for the stories that were printed about him the day after he was fired. After all, how employable could you be when The New York Times mentions your name in an article titled “Schlitz Discharges 3 Executives in Reaction to Kickback Inquiry”?

According to the Milwaukee Sentinel, Martin’s suit accused the company of “disseminating throughout the brewing industry libelous statements saying he was ‘guilty of illegal and/or unethical acts.’ ” If you believe the SEC and its 747-count indictment, then Martin had just filed a lawsuit against the company for which he was committing criminal activity—for bad-mouthing him for that criminal activity.

Schlitz’s Tap Runs DryOn October 31, 1978, Schlitz settled with the SEC by pleading no contest to a single count of criminal conspiracy; failing to keep accurate, permanent records for tax purposes; and paying millions of dollars to retailers to persuade them to sell Schlitz beer. However, this mea culpa didn’t forestall the inevitable. Due to the massive egos within the company and the disastrous tone-deaf business decisions they made—along with the mishandling of the government indictments and Martin’s ongoing civil lawsuit—the once billion-dollar behemoth that was the Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company became a shell of itself, an afterthought.

Perhaps the final blow that killed off Schlitz came in the form of a 1981 labor strike. Seven hundred manufacturing-plant workers walked off the job in Milwaukee in a monthslong labor dispute, and shortly thereafter the company announced that it would be closing its legendary Milwaukee plant forever.

Schlitz was now lying facedown in the corporate gutter, bleeding money. Rivals circled the lifeless beer maker. In 1982 the Stroh Brewery Company bought Schlitz for a paltry $500 million in cash—roughly the revenue Schlitz would pump out in a decent quarter in the 1970s. Even with the acquisition, though, Schlitz and Stroh together were still a distant third in sales behind Anheuser-Busch and Miller. In the decades after, the company was sold two more times to massive conglomerates. Today, ironically, Schlitz is owned by a onetime local competitor, Pabst, which itself is now pretty much a holding company that acquires heritage beer brands.

In 1985, seven years after launching his lawsuit, a victorious Martin stepped over Schlitz’s lifeless corporate body in the streets of Milwaukee. A jury handed him a hefty $1.3 million judgment (though a judge later trimmed the amount, deeming it excessive). Martin leveraged his triumph into a coveted marketing job in California, far away from Milwaukee and the beer wars. His career flourished, and he and Kaye moved into an opulent home they cheekily referred to as the House That Schlitz Built.

There were winners in the beer wars, but Schlitz wasn’t one of them.

esquire