The Italian publishing phenomenon that humorously revives the shadows of terrorism during the Age of Lead.

/

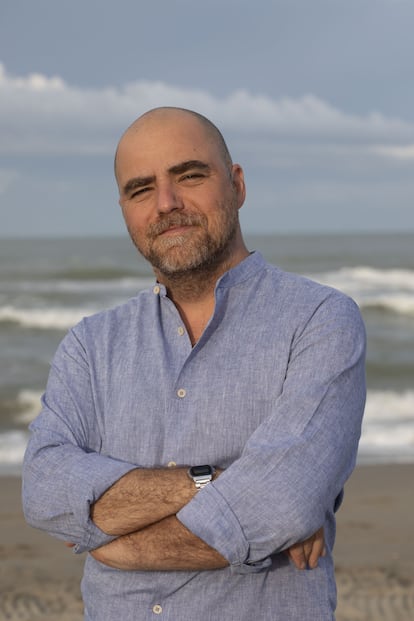

When asked about his future as a teenager, Dario Ferrari (Viareggio, 43) replied that he wanted to be a messiah. Not because he had excessive ambitions, but because it was an effective way to end the conversation and avoid having to answer truthfully: he had no idea. Today, he thinks it's great that a kid fresh out of high school is going through the same doubts. "When my students tell me they don't know what to do with their lives, I think it's great. It's an excellent starting point, because it allows them to open up to possibilities," says the writer and high school teacher. Libros del Asteroide has just published his novel Se hace el recreo (Recess Is Over) in Spain (translated by Carlos Gumpert), which became a true publishing phenomenon in Italy.

Uncertainty is the starting point of this satire starring Marcello, a 30-year-old man who hasn't been able to make a single important decision in his life. The young man repeats to himself like a mantra that he has plenty of time to "be complete" (alluding to Italo Calvino's famous phrase, "sometimes one believes oneself to be incomplete and is only young"). The reality is that he is a professional procrastinator, taking more than a decade to graduate in Literature. When time begins to run out, and his father pressures him to keep the family bar, he wins a scholarship for a doctorate at the university.

Recess Is Over begins as a scathing critique of an academic world that is merciless toward outsiders who, like Marcello, don't play by the rules. A world Ferrari knows well, as he, like his protagonist, also completed three years of a doctorate at the University of Pisa. "It was clear to me from the beginning that I wasn't going to stay in that world. I didn't do anything to achieve it, and no one took a particular liking to me enough to take me under their wing. But it was a divorce by mutual consent; no one suffered," the writer assures.

Even so, those three years studying French post-structuralist philosophy were well spent. “Since no one had much hope for my work, they let me travel a lot. I spent time in the United States and Paris, without anyone demanding anything of me.” The stories and conversations he experienced during his doctoral studies were one of the main inspirations for the novel, although Ferrari never intended to focus his story on this aspect.

His starting point was, in fact, Italian terrorism in the 1970s . The need to investigate that dark decade of Italian history, which culminated in the assassination of former Prime Minister Aldo Moro at the hands of the Red Brigades, gave rise to the parallel plot of Recess is Over . “As a history teacher, I realize that when we reach the years of lead in class, there is something I fail to convey to my students,” he explains. “I didn't understand how it was possible that the desire for liberation, for overcoming exploitation, could end with bloodshed in the streets.”

“I asked myself if I really had the right to write a historical novel about this period. I'm not an expert, a witness, or a historian. So I decided to have that story told by Marcello, someone who doesn't fully understand it either, and who has even more limited tools than I do.” When it came to choosing a topic for the thesis, Professor Sacrosanti—whose name leaves no doubt about the power he wields in the faculty—assigned him to research a certain Tito Stella, a virtually unknown young writer-terrorist who died in prison. The character, sprung from Ferrari's imagination, moves on the periphery of the armed struggle, far from the large cities like Rome or Milan where terrorist groups usually operated.

Generations facing each otherWhen Marcello begins to search through Tito Stella's letters, the contrast between the two generations becomes evident. And although the differences outweigh the similarities, the two characters, separated by fifty years of history, share a disillusionment with the future. Tito was taken away by terrorism and prison. Marcello and his university classmates were affected by power struggles and the crushing precariousness of the academic world. "I am convinced that Italy is not a country for young people. There is a very clear attitude toward them: they are told to stay where they are and wait, hoping that one day something will happen. But this something, for many, never arrives," Ferrari acknowledges.

When the book was published in Italy, Ferrari was prepared for criticism from both sides. More came from the academic world, determined to unravel the identity of the professor at the University of Pisa who inspired him to draw the character of Sacrosanti. “I haven't received any criticism about terrorism, neither from the right nor the left. I don't know if that's a good or bad thing,” he quips. Probably, he acknowledges, the novel's lighthearted tone and the fact that it's set far from the main scenes helped him avoid criticism from those involved in politics during those years.

Two years later, Ferrari still hasn't solved the problem of how to talk to his students about terrorism. And it's not because they aren't interested in history. "It's easy for them to understand why someone was willing to die in the 19th century for a constitution, or to fight fascism. But they can't understand how, 50 years ago, someone could kill another person out of nowhere because of the almost hallucinatory conviction that a civil war was underway," he explains. He also acknowledges that it's a widespread problem.

—Can we talk about an open wound in Italy?

—It seems to me that we decided to repress it. We wanted to quickly close that experience. And that's something we do in Italy quite often. Even with fascism. We tell ourselves it was just a parenthesis , a temporary detour that we can pretend didn't happen. But it was 20 years of history that we're still dragging along.

EL PAÍS