War in Books: A Survey of What Russians Read to Understand Themselves

Ansa photo

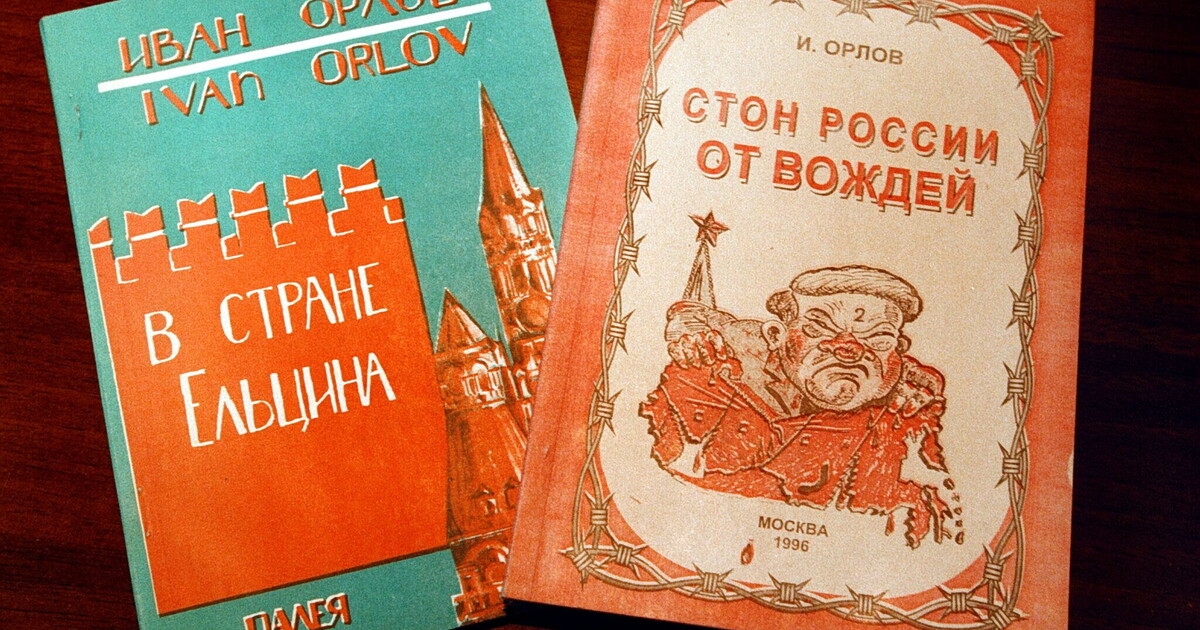

Russian readings

Less war celebration, more reflection. After the invasion of Ukraine, something has changed in Russian citizens' reading habits.

After the invasion of Ukraine, the war also entered Russian bookstores. In the months following February 2022, as the Kremlin multiplied censorship laws, courts condemned anyone who dared to utter the word "invasion," and the media repeated the rhetoric of "denazification," readers began to look to war history books and fiction for a language to orient themselves. Initially, they did so in the direction predicted by propaganda: rediscovering the myth of the "Great Patriotic War," the epic memory of the struggle against Nazi Germany . Titles recounting the resistance of Stalingrad, biographies of Soviet heroes, and novels celebrating collective sacrifice once again dominated the bestseller lists. Reading, in those months, meant joining in.

Then something changed.

Young political scientist Natalia Vasilenok conducted a broad survey of Russians' reading habits between 2018 and 2025 (the paper is freely available online under the title "Reading Orwell in Moscow"), combining data from the country's main bookstore (Chitay-Gorod) with data from the LiveLib platform, the largest online community of Russian readers. Using a textual analysis model, she reconstructed the "latent themes" that dominate Russian historical nonfiction and followed their evolution after February 2022. The picture that emerges is shifting and contradictory: from the registers of propaganda, a gradual shift is taking place towards a freer, even subversive, use of memory. Indeed, already in 2023, a shift in tone is evident. Readers continue to read about war, but no longer simply to celebrate it. The same texts that once fueled national pride are beginning to be interpreted differently, as tools for reflection or doubt. Vasily Grossman's " Life and Fate ," for example, returns to the spotlight not as an epic of Soviet victory, but as a novel about identity crushed between two totalitarian regimes. Svetlana Alexievich 's " Secondhand Time: Life in Russia after the Collapse of Communism " and " War Has No Woman's Face: The Epic of Soviet Women in the Second World War " are also being read with a fresh eye, as investigations into the fragility of truth and the violence of power.

The very memory of war that turns into a moral question. Vasilenok calls this phenomenon "ambiguous reading practices": texts capable of speaking multiple languages, depending on who opens them. A patriotic novel can be read as a parable of fear; a war diary as a reflection on obedience. History, in other words, becomes a coded language. George Orwell's 1984 and Animal Farm, Hannah Arendt's The Origins of Totalitarianism, Anne Applebaum's Gulag, Timothy Snyder's Bloodlands and On Tyranny become reference points for those seeking analogies with the present. Added to these are Horst Krüger's The House That Blew, the memoir of a young German raised in the normality of Nazism and then forced to live with his own "guilt without crime," and Tova Friedman's Daughter of Auschwitz, the story of a survivor who transforms memory into an exercise in awareness. These books don't openly denounce but teach us to read between the lines. Thus, the contours of a silent transformation are emerging. In a system that controls information and punishes public speech, reading becomes a way to think without exposing oneself. The forums and comments on LiveLib display a cautious language, full of allusions, where "guilt," "fear," and "shame" replace now unpronounceable political terms. History serves to express what cannot be said about the present. Even the publishing industry seems to be reacting. After 2023, books dedicated to moral dilemmas, daily life under regimes, and the banality of obedience are multiplying; those celebrating collective greatness are diminishing. It's as if readers' demand for meaning has forced the catalogs to strike a different balance between memory and rhetoric. The readership targeted is limited: mostly young, urban, educated, and connected. But it is there, in the most exposed segments of society, that historical memory becomes a terrain of resistance. Reading is not necessarily a political act, but under certain conditions, it can become one. In a Russia that imprisons poets and philosophers, books remain one of the few spaces of freedom: the possibility of constructing unmonitored thought. In a country that has built its legitimacy on the heroic memory of the Second World War, the renewed interest in the dark side of the twentieth century—collaboration, cowardice, fear—is a sign of a crack in the official narrative. It's as if the image of the "Moscow Orwell" evoked by the title of Vasilenok's essay weren't a simple intellectual game, but the portrait of a public that, to survive its own time, is relearning to read between the lines: a new way to circumvent the meshes of an increasingly suffocating censorship. It is the moral biography of a segment of contemporary Russia, one that, silently, leafs through the pages of other totalitarianisms to understand its own.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto