Erkin Öncan: What did I experience in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region?

Erkin Oncan

As a group of journalists from Türkiye, we spent a week in China's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, organized by the New World Research Center, making important contacts and observations.

Our trip also resonated in the Turkish press. Right-liberal circles, in particular, portrayed it, as they do with every Xinjiang trip, as "a plan by the Chinese state."

In journalism, how it's expressed is as important as what it actually is. For example, while a trip organized within a state's borders with that state's "permission" or "invitation" is perfectly acceptable under "normal circumstances," the same scenario can easily be portrayed as part of a "conspiracy" depending on the political structure of the state in question.

In the Chinese case, the same tactics have been employed for years, particularly in Western media, regarding China and the Xinjiang region. The concept of "sovereignty," comprised of borders, rules, and regulations, is treated as a "model of oppression" narrative when it comes to China.

The "if we do it, it's good, if our enemies do it, it's bad" mentality, rooted entirely in anti-communist ideology, is certainly felt in Türkiye as well. Add to this the narrative of "captive Turks" and "Muslims oppressed by communism" from Cold War Turkey, in the context of our historical ties with the Uyghurs. The Uyghur issue has become an untouchable, unquestionable, and unpromptable "sensitivity" in Turkish mainstream politics, from right to left.

Moreover, if the region in question is the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which is almost at the center of the jihadist terrorism that has ravaged the Middle East and Central Asia and the color revolution ideology that "overthrows regimes" with its narrative of freedom, and which shares borders with eight countries: Russia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, things get even more complicated.

In Türkiye, travel delegations to Xinjiang, especially those composed of journalists, are constantly forced to carry these kinds of questions in their backpacks. Is Turkishness and Islam banned in the region? Is the communist regime oppressing the people? Are Uyghurs forced to work in factories? Is a Chinese man placed in every Uyghur family's home?

That's why I began this article with such a long introduction. Of course, given my worldview and as a journalist who closely follows the narratives painted by the media arm of imperialism, particularly China, through disinformation, I was aware that news about the region had political, not social, objectives.

However, a one-week research trip is still insufficient to cover the entirety of this region, China's largest administrative region. This 1.66 million square kilometers is equivalent to slightly more than twice the area of Türkiye. In other words, even if all of Türkiye were included within Xinjiang, approximately 880,000 square kilometers would remain unoccupied.

Our trip, which began in Urumqi, the capital of the autonomous region, concluded with visits to a number of religious, official, and historical sites, including the Islamic Academy and historical/current museums in Urumqi, the ancient water channels (karızs) that are thousands of years old and consist of thousands of water tunnels carrying the water basin of the Tian Shan and Yanan Mountains to Turfan, the Jiaohe Ancient City, the old city in Kashgar, and the Iygdah Mosque.

The entire region was quite interesting and educational. However, in this article, I want to focus more on my personal experiences and impressions from outside of official visits.

There are many important historical realities, particularly regarding the Xinjiang Uyghur region, that are overlooked in Türkiye. Therefore, when examining the region, it is essential to fully grasp the extent of the region's political and social relations with the Chinese. The current narrative is replete with indirect implications that almost promote the idea that China "invaded the region a few decades ago." Yet, the Uyghurs, in particular, are a people inherently part of the region and have historically had close interactions with the Chinese.

The relationship between the Turkic peoples of Central Asia, both with the Chinese and with each other, is quite complex. The peoples of the region, especially the Uyghurs, engaged in numerous interactions, both alliances and wars, both with the Chinese empires and among themselves. For example, the Uyghurs, who fought the Chinese during the Han Dynasty, suppressed rebellions alongside them during the Tang Dynasty. Similarly, the Uyghurs, who were engaged in fierce power struggles with the Göktürks throughout their history, lost their sovereignty due to Kyrgyz attacks, and held important bureaucratic positions during the Mongol era.

These historical examples, which can be viewed both favorably and unfavorably, are countless. Therefore, we must explain the complex relationships of history, our recent history, and the complex relationships of the present day using historical and social science concepts such as sovereignty, state, market, revolution, and power. Any perspective that fails to do so objectively ends up defending radical Islamist terrorism, pro-Western separatism, and color revolutions.

This is precisely what is happening in the debates surrounding Xinjiang today. The world and Turkey, gripped by an information network of false news, are searching for Turkishness and Islam not in the region's own living conditions, but through the light of radical Islam and pro-American ideology.

Allegations that Uyghurs live under oppression

During our week-long exploration of three distinct regions of the autonomous region, I was particularly careful not to deviate from the route except in areas where Chinese authorities had "led us" to tour. I didn't rest during any of our "rest hours" but took to the streets. I'd also like to note that I encountered no objections from our Chinese guides who accompanied us throughout the trip to the free-roaming streets.

As soon as I arrived in the capital, Urumqi, I dropped off my bag at the hotel, left, and began wandering the streets of Urumqi, a city I'd never seen before. The first thing I noticed was how spacious and modern the city was.

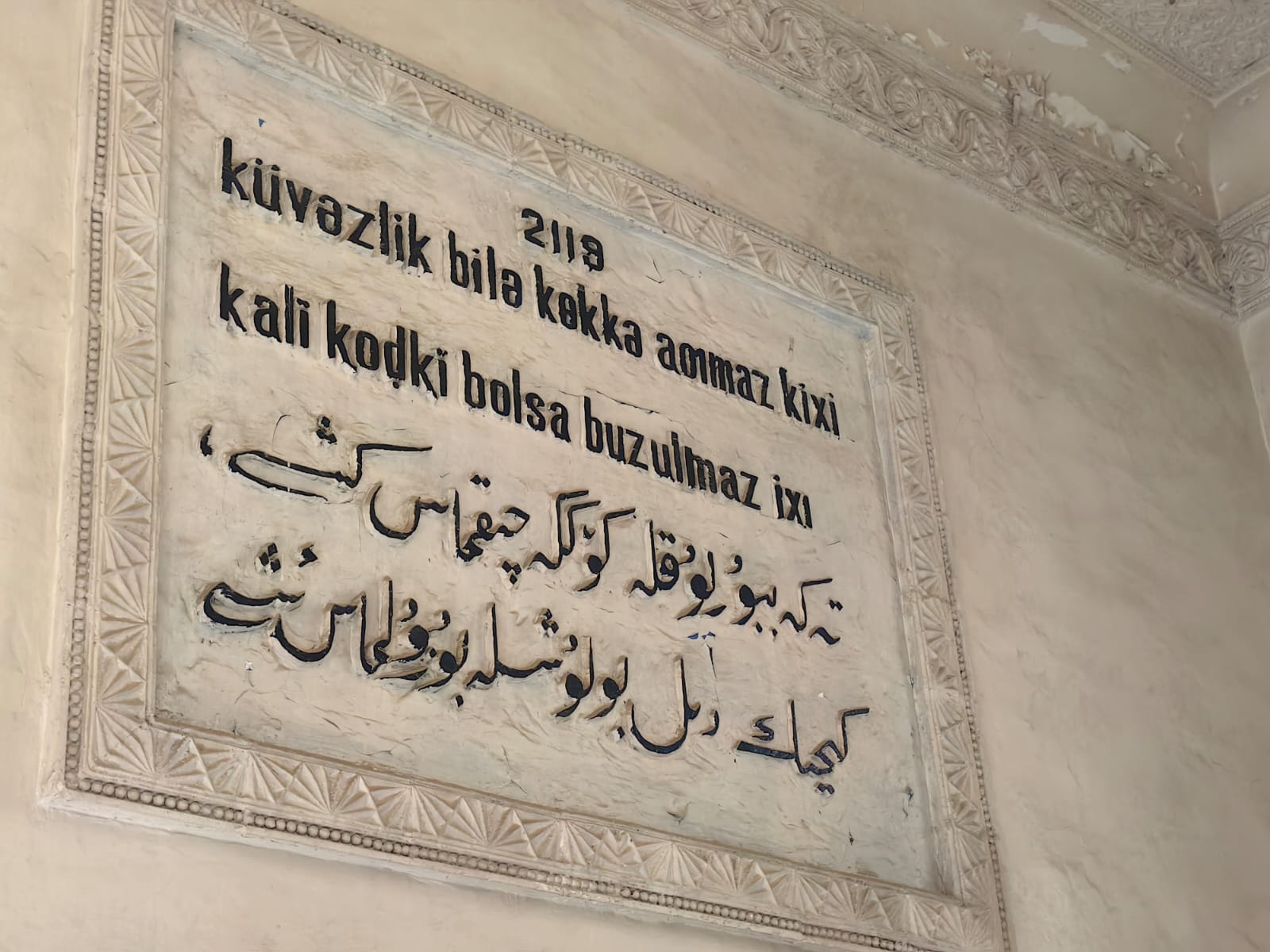

It's been written and reiterated many times, but let's reiterate: Wherever you go in the autonomous region, life is multilingual. Shops, official statements, signs, voice announcements, menus, even currency—all are simultaneously published in Chinese and Uyghur.

Likewise, Uyghurs can use their own language in university exams and education.

While wandering around Urumqi, I had the opportunity to examine the "facial recognition systems" I've frequently seen in Western media. When entering neighborhoods in the area, people use facial recognition systems, and the "neighborhood gate" opens. Incidentally, the same system applies to the Chinese. I entered through the gate that opens after someone enters their neighborhood. Upon entering, I told the security officer I wanted to walk, but I wasn't met with any objections.

The neighborhood I was visiting was an ordinary one, consisting of houses and shops. Uyghurs I asked about the system said it was implemented for security reasons.

On the other hand, I didn't see any police in the neighborhood, and there are very few in the area overall. The police I did see were unarmed.

I was also struck by the notices on nearly every house and shop door. These notices include the names and phone numbers of the police officers on duty in the area that week. Citizens are asked to call the numbers or scan the QR code on the notice when police are needed. The same system applies to healthcare procedures.

During my wanderings, I came across two "neighborhood fights." In both cases, civilians wearing red armbands arrived to break up the fights, not the police, and the matter was resolved smoothly.

It appears that the Chinese government largely relies on digital automation to maintain public order in residential areas. Basic public order matters have been delegated to local volunteers and various centers.

During our trip, we also visited a neighborhood center that functions similarly to our neighborhood headman's office. The center houses a bank, police, and civil servants' offices. Similarly, an online lawyer is available 24/7 for those seeking legal advice. These centers also feature a game room, massage room, and a social media room where residents can create TikToks.

At the neighborhood center, residents also have access to essential health and cleaning products. Similarly, there are shelves stocked with items that citizens can collect for free with the "points" they accumulate by sweeping their front doors or participating in social assistance.

This whole system may be seen as 'oppressive' by advocates of the 'police state' model, where an armed police team is on standby at every corner.

Allegations of religious and cultural oppression

During our visit, we also had the opportunity to visit numerous religious centers and mosques. Of course, I made sure to visit these places on my own during my downtime, outside of my official tour.

There are numerous reports in Xinjiang claiming that mosques are "empty." Indeed, no one spends much time in mosques outside of prayer hours. A Uyghur citizen I asked about this question responded by pointing to a place I saw on almost every street I walked, a place that served both food and drinks.

I need to make a point here: Uyghurs are truly very social people. Large numbers of Uyghurs, men and women, young and old, are out on the streets late into the night. Unlike ours, in Uyghur culture, dining and cafe/bar-like spaces are not separate, but rather structured as a single space.

This entire system may be perceived as oppressive by those who defend a faith-based "uniform society", who see mosques or religious centers as the sole social space, who long to define the public sphere according to religious belief, and who want to design life solely according to religious rules.

Allegations of political pressure

While the Communist Party of China is the country's ruling party and its largest force, it is not the only political party. China has a complex political system, consisting of national people's congresses, delegate systems, and what they call "people's democracy," where each party leader holds a ministerial or vice-presidential position. This stems from the fact that the Chinese revolution is also a "revolution of alliances."

Therefore, as in other parts of China, the only party in Xinjiang is the CCP.

While party symbols and the hammer and sickle symbol are frequently seen in public spaces, unlike in our country, I've never seen a portrait of the head of state (Xi Jinping). A CCP member I asked about this explained that this is related to the party's institutional identity. What matters is the party itself, not the individual party official. Therefore, portraits of heads of state are rarely seen in public spaces in China—with the exception of historical figures like Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping.

The CCP is a party that holds a commanding position over all political affairs. China considers itself to be at the "early beginning of the primary stage of socialism." Its constitutional definition is "a socialist state under the people's democratic dictatorship." The CCP is seen as the political instrument that will ensure people's sovereignty.

This entire system may be seen as oppressive by advocates of a 'Western democracy' that operates under the rules of a capitalist market economy, has symbolic 'representation' and is dominated by monopolies, or a 'Sharia state' where the single power is shaped according to the religious understanding of the structure in question.

Claims of 'oppression of Turkishness'

Another of the most frequently made claims regarding the Xinjiang Uyghur region is that "Uyghurs are unable to live their Turkish identity." It's crucial to note that not only China but also Turkic peoples living in former Soviet countries have very different understandings of Turkish nationalism from the one developed and supported by the CIA during the Cold War.

It's clear we're related to the Uyghurs. It was truly a great pleasure to be able to get along with Uyghurs, even if only at a rate of about 40 percent, in the places I visited. I asked every Uyghur I met the following question, a question I'd planned to ask before I even left:

“Are you Turkish?”

All the Uyghurs I spoke with gave roughly the same answer. They believe that Turks and Uyghurs are brothers and relatives, but are separate peoples. Without exception, all of them said they were "Chinese citizens and Uyghurs." Of course, some would see this as a "result of CCP propaganda." However, we also witnessed with our own eyes the strict protection of the heritage of the Uyghurs, and more broadly, the Turkic world.

The mausoleum of Yusuf Has Hacip, author of the Kutatgu Bilig, the first political treatise in Turkish literature, and the first to use the verse form, was particularly striking. The presence of Yusuf Has Hacip's works in both Latin and Uyghur script on the tomb's walls, and the fact that the tomb is recognized as a significant cultural heritage site, offer important insights into the government's perspective on history.

These facts may also be seen as 'fake' or 'oppressive' by advocates of a Western-backed political 'union of states' defined as 'Turan', which has almost no political power in other countries belonging to the 'Turkic world'.

Allegations of forced labor

During our trip to Xinjiang, we also visited important production centers and factories. For example, a textile factory processing cotton was quite striking. However, unlike forced labor, I saw few workers.

Regarding the allegations of "forced labor" that have been prominent in the world press, it can be said that "we were taken to factories where there was no forced labor", or even that "the workers were hiding somewhere just because we were going."

Although there are those who seriously defend such claims in Türkiye and around the world, the fact that a significant portion of factories operate with advanced automation systems raises some question marks.

For such claims to be true, I believe everything we saw had to be for show. This amounts to believing that the Chinese government has built a massive film set, spending billions of dollars on groups of journalists who visit the region several times a year, simply to bolster their claims.

Of course, these claims may be found 'oppressive' by those who defend the conditions of brutal competition of the capitalist market economy, with its rhetoric of 'equality of opportunity' and 'free enterprise', rather than a production force centrally planned by the communist party.

Was there no negativity?

It is possible to describe our Xinjiang trip in general with two concepts: prosperity and development.

These two concepts are the main goal, the main concern and the main source of pride for both the Uyghurs and the Chinese living in the region who are in official/administrative positions.

All of the problems claimed to exist in Turkish and Western media have been resolved to an irreversible extent with these two concepts.

So was there no negativity? Of course there was. Moreover, it was surprising to see that none of the negative aspects I encountered were present in Turkish or Western media, yet these issues were actually on the agenda and being discussed openly in China.

The Chinese central government is making significant investments in Xinjiang autonomy, and these investments are expected to continue. However, some Uyghurs I spoke with—especially young people—believe the investments should come faster.

Moreover, in Kashgar, where there is a large Han Chinese population, I suspected there might be some sort of class difference between Chinese and Uyghur. While the larger department stores, well-known brands, and shops selling expensive goods were almost all Han Chinese-owned, the smaller, more squalid shops, focused on food and tourism, were owned by Uyghurs.

I asked a Han Chinese CCP official I met in the region about this observation. He said my observation was entirely accurate, adding that the income gap between minorities and the center was closing over time, and that closing the gap completely was among the CCP's official, written goals. After my conversation with the official, I concluded that it would be more beneficial for my distant relatives living in the region to follow such investments rather than deal with the constant stream of false news.

I also asked the same official I spoke with whether, in Xinjiang and throughout China, concerns about the future, rather than ideological affiliation, were becoming a determining factor in party membership applications, particularly among young people. This was a question I was genuinely curious about. The official believed that ideological affiliation also influenced young people's applications, but he did not reject my observation, describing it as a "real sign" and stating that educational and propaganda activities were actively underway to counter this.

I asked a Uyghur CCP member, whom I met at a karaoke bar in Urumqi, whether he shared my view and what he thought about it, saying that due to intense domestic tourism in the Xinjiang region, there was a risk of Uyghur culture and historical sites becoming a kind of 'tourism object'.

He rejected my observation, claiming that I found it remarkable because I was "an outsider." We arranged to meet up and tour the villages on my next visit.

My week-long study trip to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region revealed to me, first and foremost, how little is known about the Uyghurs and China in our country. Moreover, there are 56 ethnic groups in the country, including the Uyghurs.

What shapes the perception of the region is not the sources belonging to the region, but the propaganda activity shaped by a one-sided, passive and, most importantly, right-liberal ideology, in which all sources belonging to the region are considered lies and 'CCP propaganda'.

Let's ask our readers, especially those skeptical of the Xinjiang issue: How many statements made by the Chinese regarding Xinjiang, and even China, have you read directly from the source, directly from Chinese news agencies, without any Western agency transmission? Your answer to this question will offer important clues about the one-sided propaganda you've been exposed to.

For all these reasons, as I walked the streets of Kashgar, the final stop on our trip, I thought more about my own country than about the Uyghurs. We know so little about this vast, autonomous region, with its pros and cons.

Tele1