The Neoprime Club: Silicon Valley and The Rise of Defense Disruptors

OPINION — Today, after a post-9/11 era defined by global counterterrorism and asymmetric warfare, the U.S. is preparing for potential near-peer conflicts amid an era of great power competition that is complicated by disruptive technologies. In response, a new wave of defense contractors is emerging from the epicenter of American technological innovation: Silicon Valley. These companies are addressing critical technology gaps in areas such as artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, space services, cyber operations, and small drones. They're deploying cutting-edge solutions to fill capability shortfalls that the U.S. government has acknowledged exist—and they’re scaling fast. Winning high-profile contracts, these companies are reshaping how the Pentagon engages with the private sector.

Among those in the defense tech industry, there’s been growing chatter about the rise of these defense disruptors—what you might call the neoprimes. We—one of us a technology investor, the other a former portfolio manager at the Department of Defense’s Defense Innovation Unit—are often asked: Is the rise of neoprimes real? What exactly is a neoprime? What defines one? We set out to answer those questions, using data to support our observations. We believe neoprimes are changing the culture of defense acquisitions and developing technologies that will reshape how wars are fought. Shifts in defense spending and policy are empowering neoprimes to grow and move faster.

To understand how we got here, we can revisit a pivotal 1993 meeting now known as the “Last Supper.” Following the end of the Cold War, U.S. defense spending plummeted, prompting a major drawdown. The Department of Defense faced intense pressure to cut costs, with budgets falling by about 30%—from, adjusted for inflation, $772 billion in 1989 to roughly $531 billion by 1998. Against this backdrop, then-Deputy Secretary of Defense William Perry convened a critical meeting, the “Last Supper,” with executives from the top defense contractors. His message was clear: the Pentagon could no longer sustain a sprawling ecosystem of dozens of major firms, and consolidation was inevitable. The industry responded accordingly—over 50 companies merged into the five dominant primes we know today. These survivors—Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman, Boeing, and General Dynamics—became massive, vertically integrated organizations that controlled roughly 60% of Department of Defense contracts by 2000. For decades, these primes dominated government contract spending to build and sustain the nation's security apparatus, supported by a vast web of partners and subcontractors. But with predictable, annual funding streams and limited competitive pressure, innovation within these primes arguably stagnated.

While many of these traditional primes trace their roots back over a century, a new tribe of Silicon Valley players has entered the arena. They are accelerating deployment timelines and pioneering a different model—defined by rapid iteration, software-first architectures, and a greater appetite for risk. They're deploying operational systems in months rather than years or decades. They’re not just building prototypes for demos and exercises—they’re scaling production and securing billion-dollar contracts. While they may not yet match the traditional primes in total contract volume, they are closing the gap year over year. A handful of key firms are leading the charge, with an expanding set of startups gaining traction. Backed by venture capital and supported by a growing network of influential advocates shaping policy and public opinion, neoprimes are starting to redefine how the government approaches the acquisition, fielding, and sustainment of new technologies. They are becoming mission-critical to the defense industrial base of America.

As this new generation of defense contractors gains momentum, what exactly is a neoprime? To answer that, we analyzed data from USAspending.gov (the federal government’s official platform for tracking public expenditures), reviewed SEC filings from public defense companies, and compiled press releases from private firms. We also interviewed founders and venture capitalists focused on national security innovation.

Through this research, we identified several defining characteristics of neoprimes and emerging market trends. Our analysis focuses on a set of current neoprimes—SpaceX, Palantir, and Anduril Industries—alongside a cohort of rising companies like Shield AI, Skydio, Saildrone, Saronic, Hidden Level, Epirus, Relativity Space, Axiom Space, HawkEye 360, Vannevar Labs, and others. These companies are beginning to lead major defense programs with advanced technologies and a fundamentally different approach to speed, software integration, and delivery.

Below, we outline our findings and define the characteristics that distinguish neoprimes. We believe these companies represent the future of national security—and to preserve America’s strategic edge, we must rapidly adopt and scale their solutions across the defense industrial base.

Join us in Sea Island, Georgia for The Cipher Brief's 2025 Threat Conference from October 19-22. See how you can save your seat at tcbconference.com

Neoprimes are Racing Ahead in Department of Defense's Critical Technology Areas

At their core, neoprimes are built around emerging, frontier technologies—fields like AI and autonomy, integrated networks, biotechnology, and quantum science. In recent years, the Department of Defense has formally emphasized the importance of these technologies, identifying fourteen Critical Technology Areas that reflect a growing urgency to catch up with and surpass global competitors.

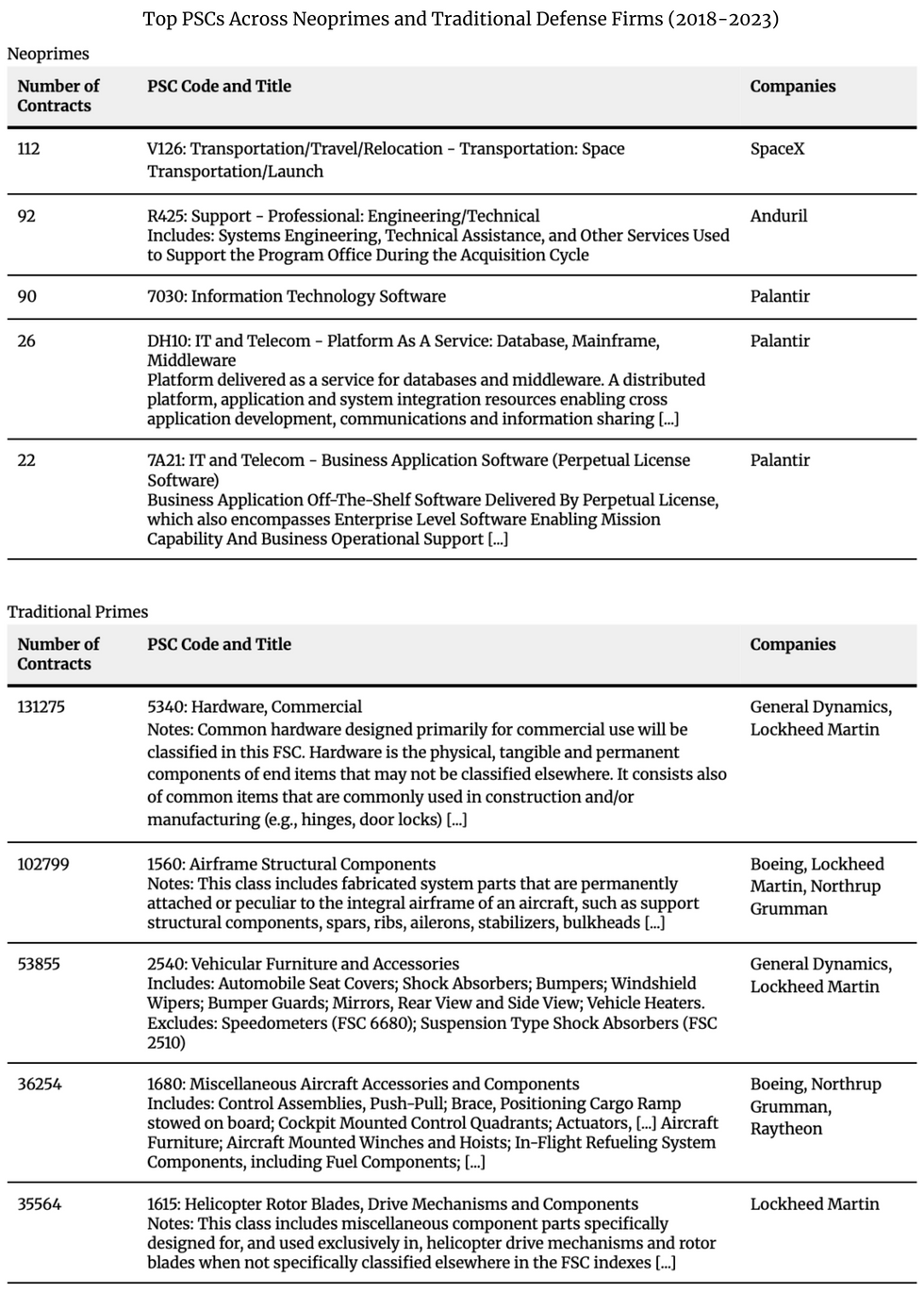

To better understand this trend, we evaluated the top five most commonly used Product Service Codes (PSCs) for a set of government contractors from 2018 to 2023. PSCs are used by the U.S. federal government to describe the products, services, and research being purchased through contracts, and we gathered this data from USAspending.gov’s contract award summaries by vendor. For Palantir, SpaceX, and Anduril, we then identified the most popular PSCs across all three. We performed the same analysis to determine the top PSCs among the traditional defense primes—Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman, Boeing, and General Dynamics.

Palantir's top PSCs were predominantly in the information technology category, consistent with their core strength in data platforms and software integration. Most of the PSCs associated with Anduril were concentrated in engineering services.

In contrast, for traditional primes such as General Dynamics, Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon, the most common PSCs were heavily concentrated in hardware categories—covering items like airframe structural components, helicopter rotor blades, and shock absorbers. Compared to newer entrants, their portfolios featured far fewer PSCs related to software or IT services.

Neoprimes are also focused on interoperability. Traditional contractors are notorious for proprietary systems that require their own unique control systems and limited third-party integrations—like drones that can only be operated with specific controllers, computers, or field kits. But proprietary everything doesn't scale on a battlefield increasingly filled with robots, sensors, and drones, especially as soldiers are limited by the number of control systems they can carry into the field. In contrast, neoprimes are designing software with interoperability in mind from the start—built to integrate seamlessly with legacy systems and ingest any data the government allows.

Overall, the solutions neoprimes are developing are especially relevant today, as many Cold War-era tools are failing to scale to the demands of the modern battlefield. For example, Ukrainian soldiers are now using low-cost drones to disable expensive Russian platforms—in the recent Spider's Web operation, 117 drones struck four Russian military airbases and targeted at least 40 warplanes. The operation dealt a significant asymmetric blow to the Russian military and broader economy, with estimated losses reaching up to $7 billion. The inevitable shift toward more affordable, more attritable platforms is forcing governments to rethink how they develop and fund major defense systems. Neoprimes and the Department of Defense are racing to develop low cost-to-kill technologies—while also developing defenses against them—as these small lethal platforms become increasingly common on modern battlefields around the world.

Sign up for the Cyber Initiatives Group Sunday newsletter, delivering expert-level insights on the cyber and tech stories of the day – directly to your inbox. Sign up for the CIG newsletter today.

Prototyping and Collaborating Directly with Servicemembers

Neoprimes build working prototypes quickly and make a habit to iterate with end users in real time—making changes on the fly, in the field. We have observed that these companies don't necessarily wait for the Department of Defense to fund their R&D; instead, they develop solutions they believe are obvious answers to current pressing problems and find ways to get them into the hands of warfighters—often well before any large procurement orders have even been placed.

These companies will send prototypes "downrange" with willing servicemembers, sometimes years before more formal procurement contracts materialize. Shield AI, for example, deployed working prototypes of their AI-enabled drones to Special Operations Forces in combat in the Middle East, gaining critical feedback while also delivering real-world results for those early adopters. Other companies have taken similar approaches: deliver cutting-edge technology to warfighters first—even before any formal requirement exists—refine it in the field, and let the bureaucracy catch up later.

While we are encouraged by these bold efforts, we also recognize that rapidly deploying cutting-edge technology is not enough. What matters most is enabling and rewarding companies that deliver measurable impact on mission outcomes and operational effectiveness. We urge the Department of Defense to prioritize this focus across both traditional primes and neoprimes.

Delivering On Time and Within Budget

Neoprimes often prioritize outcomes over processes. For instance, Palantir was recently awarded a $178 million contract by the U.S. Army to develop the TITAN system, beating RTX Corporation in a competitive selection process. Remarkably, Palantir delivered the project on time and within budget—traditionally a rare feat in defense contracting.

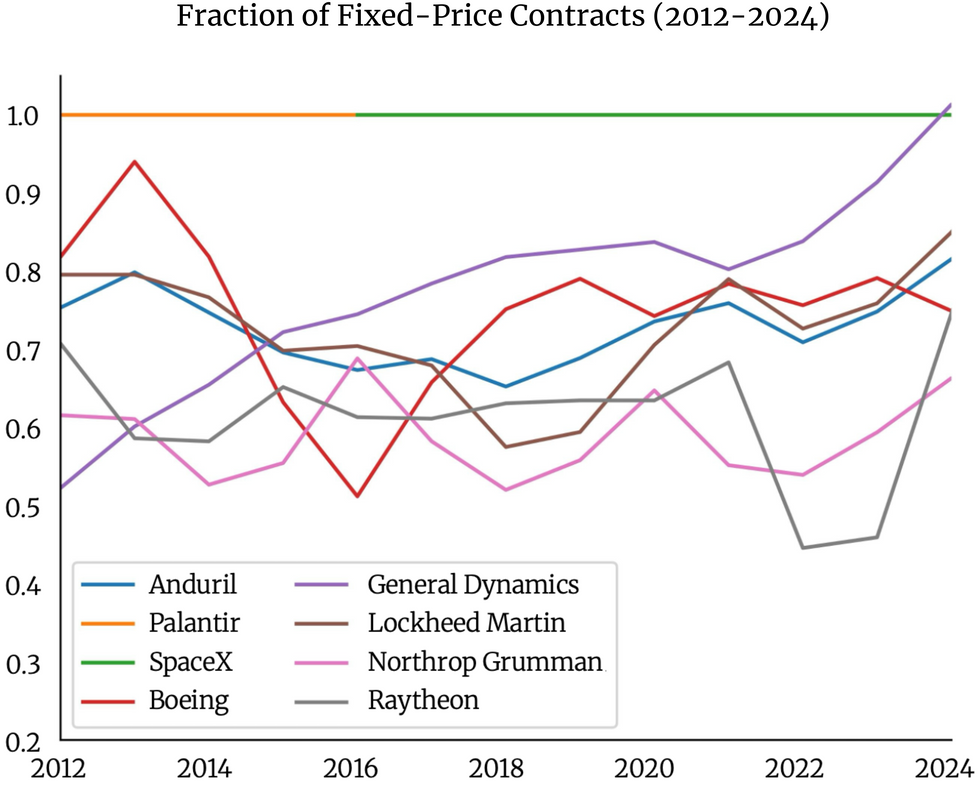

As one example of neoprimes' outcome-first approach, we have observed a growing preference for fixed-price contracts over the traditional cost-plus model. Under a fixed-price structure, companies are incentivized to innovate efficiently, as they are paid a set amount regardless of overruns. This stands in stark contrast to cost-plus contracts, where incumbents are reimbursed for all expenses and earn a profit margin on top—removing much of the pressure to operate leanly.

When analyzing government spending data, we observed that nearly 100% of Palantir and SpaceX's contracts are fixed-price, while 65-80% of Anduril's contracts follow the same model. Among the traditional primes, General Dynamics has steadily secured an increasing number of fixed-price contracts, and the trend is less clear for others.

That said, both neoprimes and traditional contractors continue to rely on cost-plus contracts, as they remain the prevailing norm across much of the defense industry. We also recognize that ongoing debate surrounds the use of firm fixed-price versus cost-plus models in defense procurement. While advocates of fixed-price contracts view them as the most effective way for the government to ensure value and accountability, critics argue that fixed-price models can be too risky for complex scopes of work. A common argument in favor of cost-plus is that it provides the necessary flexibility when project requirements are uncertain or evolving.

Maximizing Revenue and Contract Value per Employee

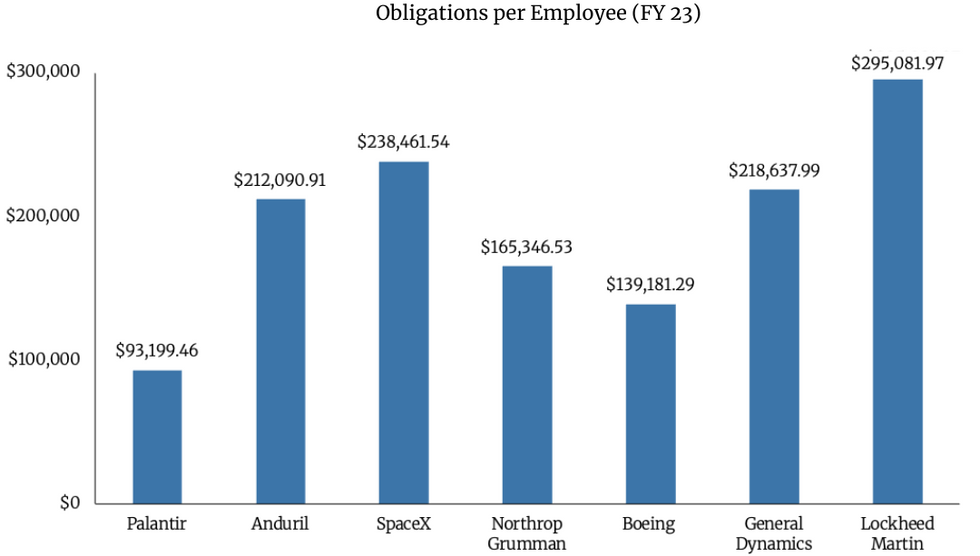

Neoprimes operate with small, agile teams—often with just a fraction of the headcount of traditional defense contractors. But what they lack in size, they make up for in velocity and output. Many of these companies are producing higher revenue or contract value per employee.

SpaceX and Anduril have outperformed several major traditional defense contractors in terms of obligations per employee, exceeding the ratios of Northrop Grumman, Boeing, and General Dynamics. And while Lockheed Martin has outperformed all in absolute terms, that may be attributed to its significantly larger revenue—approximately $51 billion compared to SpaceX's $3.8 billion.

Note that because Anduril and SpaceX are still private companies, we based their employee counts on estimates from public reports. Palantir and all traditional primes report employee numbers in their SEC filings.

Rising Use of OTAs in Defense Contracting

While Palantir, SpaceX, and Anduril are leading neoprimes, several other companies are rapidly emerging in this category. Shield AI, which began with AI-powered quadcopters for U.S. Navy SEALs and other special operations forces, is now fielding its V-BAT unmanned aerial vehicle in Ukraine, Japan, and Brazil. Companies like Saildrone and Saronic are deploying a range of autonomous drones above and below the water. Cybersecurity leaders such as Palo Alto Networks, Fortinet, and Crowdstrike are becoming key players in areas like trusted networks and digital defense. Commercial space companies like Varda, HawkEye 360, and Astranis are building capabilities for on-demand space access, persistent satellite coverage, and high-speed space-based data transfer.

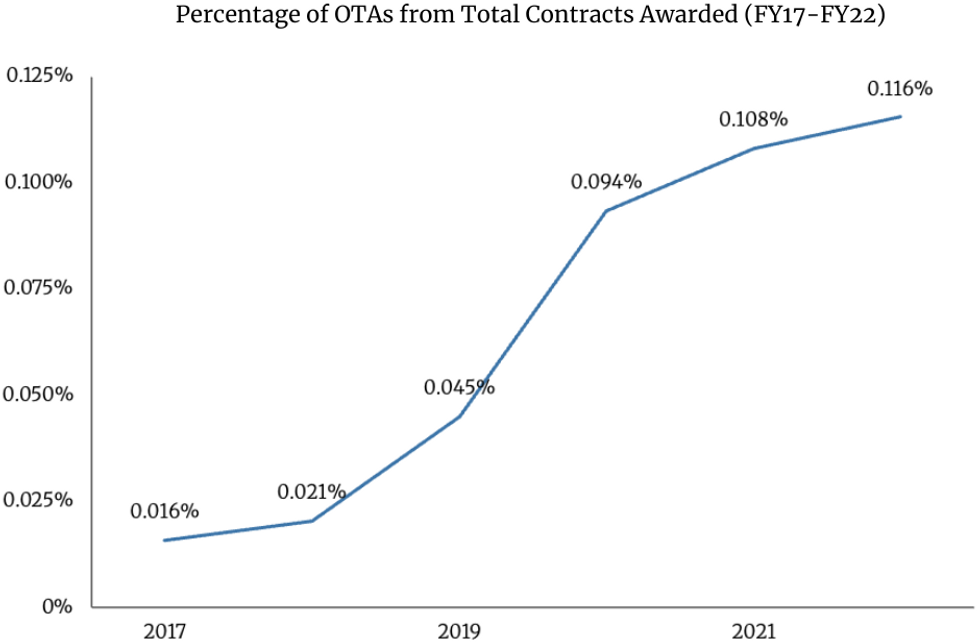

With the rise of neoprimes, the Department of Defense has significantly increased its use of Other Transaction Agreements (OTAs) in recent years, reflecting a strategic shift toward more agile and flexible procurement methods. OTAs, which are not bound by the traditional Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), allow the Department of Defense to collaborate more easily with nontraditional contractors, including startups and research institutions. When properly executed, we believe that OTAs can lead to better, faster, cheaper outcomes for everyone involved—saving time, money, and effort.

Further analysis shows that OTA usage is clearly trending upward within the Department of Defense. Even though OTA awards have increased tenfold since 2017, however, they still account for only about 0.01% of the total contracts awarded by the Department of Defense—it's still far from mainstream in the broad acquisition community. Given what OTAs have already delivered, we can only imagine the impact if more contracts were accelerated this way.

The Road Ahead: Partnering with Neoprimes to Meet Emerging National Security Needs

Today, we believe the U.S. government is beginning to recognize the strategic value of neoprimes in addressing critical capability gaps. The Department of Defense has acknowledged its lag in several key technology areas and has taken deliberate steps to close the gap. In addition to encouraging the services to expand their use of OTAs, the Department of Defense introduced the Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO) framework to attract non-traditional vendors. It also launched the Office of Strategic Capital to provide more flexible financing options and created the National Security Innovation Capital initiative to support dual-use hardware development. Over the past two decades, the Department of Defense has invested more than $20 billion in small business initiatives—all promising signs of progress, but more work remains.

Across the country, dozens of emerging technology companies are winning contracts that would have defaulted to traditional primes just a few years ago. These startups are not simply disrupting the defense industrial base; they are actively shaping the future of warfare. Their technologies are beginning to influence military doctrine, operational planning, and frontline tactics.

This shift reflects a broader transformation in national security priorities—one we strongly support and believe must be accelerated. As these threats become increasingly software- and technology-driven, we’re encouraged to see Silicon Valley and its neoprimes emerge as natural leaders in enabling the next generation of military readiness. Now is the time to double down.

Editor's Note: The authors of this article are affiliated with Brave Capital and MVA (MilVet Angels), which have invested in national security companies like Anduril Industries, Shield AI, Aetherflux, Hermeus, Ursa Major, and others.

The Cipher Brief is committed to publishing a range of perspectives on national security issues submitted by deeply experienced national security professionals.

Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not represent the views or opinions of The Cipher Brief.

Have a perspective to share based on your experience in the national security field? Send it to [email protected] for publication consideration.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief

thecipherbrief.com